American Bastard or American Badass? Jan Beatty exemplifies both in new memoir

[

{

"name": "Local Action Unit",

"component": "24929589",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

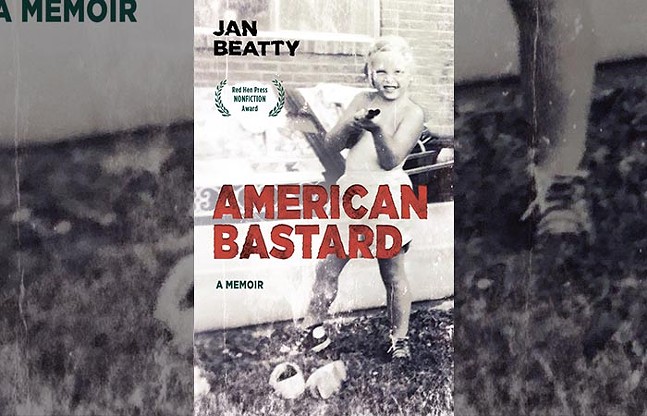

The cover photo shows a young girl smiling as she points a toy gun at the camera. At first glance, the book’s title seems to be American Badass. But the correct name of Jan Beatty’s memoir is American Bastard.

Both titles ring true. Beatty, a poet and writer from Regent Square who was adopted just after birth, calls herself a bastard throughout the book. And the sobriquet “badass” exemplifies Beatty’s determination and doggedness in searching for her birth parents.

“I knew what the cover was going to be if I ever did this book,” Beatty says of her memoir, “and I knew it was going to be red and black, and I knew what the name was going to be. I just had a vision of it, and I had this photograph from many years ago of me with a toy shotgun. I was six years old and already in high tops and shooting people, so my personality was already there.”

American Bastard (Red Hen Press) is the oft-harrowing story of Beatty’s search for family and identity while navigating life as an adoptee. Beatty recounts how she felt lost through much of her childhood, constantly afraid of being sent back to Roselia Asylum and Maternity Hospital in Pittsburgh’s Hill District.

The story took years to germinate and unfold, if not understand. About 20 years ago, Beatty wrote a story for Creative Nonfiction about being adopted, but “I couldn’t keep going,” she says. “I was already in therapy, but I needed to work on it more in therapy because there was a lot of emotional stuff in the book. And I needed to mature also as a writer because I didn’t know how to handle the material, especially in prose.”

For Beatty, being adopted came to mean never being accepted or believed. When a peeping tom climbed a ladder to her second-floor bedroom, the incident was initially dismissed as being a creation of her imagination.

“As an adoptee, you’re erased,” she says. “Your history, your name, everything is erased. So it’s really hard to be seen at all, and, then, if you have stories people don’t think are real, that’s a problem.”

To isolate herself, Beatty climbed a ladder to the attic of the family home and closed the hatch behind her. There, amid boxes and rolls of pink insulation, she lost herself in books, preferring the Hardy Boys over Nancy Drew because Carolyn Keene’s character was “too nice and they were putting her in dresses,” she says.

“I’m sitting on 2x4s and bracing myself up there,” Beatty adds about her attic refuge, “but I just needed to get the hell away from everybody and read and make little notes. I think that was me writing and saving myself because I had to live somewhere else because I couldn’t really live where I was.”

She says it wasn’t that it was horrible, but that it “didn’t have anything to do with me.”

After meeting her birth mother, Beatty sought her birth father. Going on scant clues — Beatty only knew that he had played hockey for the minor league Pittsburgh Hornets and was the team’s best player — she eventually discovered Bill Ezinicki was a golf pro in Massachusetts who had been a member of three Stanley Cup winning teams during his professional career. He was also known as a ferocious competitor, willing to doff his gloves and fight.

“You never know what you’re going to find,” Beatty says, “and I did ambush him, so he didn’t have time to prepare. I got a view of him as a human, and I really liked him.”

But two weeks later, Ezinicki called to say he wanted nothing more to do with his daughter.

About 10 years ago, Beatty traveled to her father’s birthplace in Winnipeg, Manitoba in Canada to get a sense of his life and her heritage. As a child, Beatty had been especially competitive at racquetball and softball, and she grew to believe that was due to her father’s athleticism.

But the connection she made in Winnipeg, where she got a private tour of a Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame and Museum to view some of her father’s memorabilia, was even deeper.

“Before I knew about my birth father or that I was half Canadian, I had already been riding trains back and forth across Canada, maybe four times,” Beatty says. “That’s inexplicable. Who does that? I was just driven to run around Canada before I knew, and that’s why, when I found out, everything made sense and all my history of being an athlete made sense, and fighting everyone made sense.”

While Beatty wanted to tell her story, the gist of American Bastard is about what she calls “the big lie, and the big whitewash” of adoption. Families who adopt children are often viewed as saviors, rescuing kids from lives of neglect.

But Beatty believes adoption “is not fair to anyone,” she says. “It’s not fair to the kid because everything is erased, their history is erased. It’s not fair to the adoptive parents, either, because if they’re set up to be saints, which they are, but nobody is, they have to be saints. But they need to be human, and that’s the same with all mothers,” she adds.

“There’s this thing that is placed on all women, that they’re either saints or sinners. Let’s just let people be people with their flaws and their good parts,” Beatty says. “Let’s not make everybody a savior because it’s not real. And especially for an adoptee, you need something that is real because everything real has been taken away from them, and all they have is this lie about how they got there.”

Both titles ring true. Beatty, a poet and writer from Regent Square who was adopted just after birth, calls herself a bastard throughout the book. And the sobriquet “badass” exemplifies Beatty’s determination and doggedness in searching for her birth parents.

“I knew what the cover was going to be if I ever did this book,” Beatty says of her memoir, “and I knew it was going to be red and black, and I knew what the name was going to be. I just had a vision of it, and I had this photograph from many years ago of me with a toy shotgun. I was six years old and already in high tops and shooting people, so my personality was already there.”

American Bastard (Red Hen Press) is the oft-harrowing story of Beatty’s search for family and identity while navigating life as an adoptee. Beatty recounts how she felt lost through much of her childhood, constantly afraid of being sent back to Roselia Asylum and Maternity Hospital in Pittsburgh’s Hill District.

The story took years to germinate and unfold, if not understand. About 20 years ago, Beatty wrote a story for Creative Nonfiction about being adopted, but “I couldn’t keep going,” she says. “I was already in therapy, but I needed to work on it more in therapy because there was a lot of emotional stuff in the book. And I needed to mature also as a writer because I didn’t know how to handle the material, especially in prose.”

For Beatty, being adopted came to mean never being accepted or believed. When a peeping tom climbed a ladder to her second-floor bedroom, the incident was initially dismissed as being a creation of her imagination.

“As an adoptee, you’re erased,” she says. “Your history, your name, everything is erased. So it’s really hard to be seen at all, and, then, if you have stories people don’t think are real, that’s a problem.”

To isolate herself, Beatty climbed a ladder to the attic of the family home and closed the hatch behind her. There, amid boxes and rolls of pink insulation, she lost herself in books, preferring the Hardy Boys over Nancy Drew because Carolyn Keene’s character was “too nice and they were putting her in dresses,” she says.

“I’m sitting on 2x4s and bracing myself up there,” Beatty adds about her attic refuge, “but I just needed to get the hell away from everybody and read and make little notes. I think that was me writing and saving myself because I had to live somewhere else because I couldn’t really live where I was.”

She says it wasn’t that it was horrible, but that it “didn’t have anything to do with me.”

After meeting her birth mother, Beatty sought her birth father. Going on scant clues — Beatty only knew that he had played hockey for the minor league Pittsburgh Hornets and was the team’s best player — she eventually discovered Bill Ezinicki was a golf pro in Massachusetts who had been a member of three Stanley Cup winning teams during his professional career. He was also known as a ferocious competitor, willing to doff his gloves and fight.

“You never know what you’re going to find,” Beatty says, “and I did ambush him, so he didn’t have time to prepare. I got a view of him as a human, and I really liked him.”

But two weeks later, Ezinicki called to say he wanted nothing more to do with his daughter.

About 10 years ago, Beatty traveled to her father’s birthplace in Winnipeg, Manitoba in Canada to get a sense of his life and her heritage. As a child, Beatty had been especially competitive at racquetball and softball, and she grew to believe that was due to her father’s athleticism.

But the connection she made in Winnipeg, where she got a private tour of a Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame and Museum to view some of her father’s memorabilia, was even deeper.

“Before I knew about my birth father or that I was half Canadian, I had already been riding trains back and forth across Canada, maybe four times,” Beatty says. “That’s inexplicable. Who does that? I was just driven to run around Canada before I knew, and that’s why, when I found out, everything made sense and all my history of being an athlete made sense, and fighting everyone made sense.”

While Beatty wanted to tell her story, the gist of American Bastard is about what she calls “the big lie, and the big whitewash” of adoption. Families who adopt children are often viewed as saviors, rescuing kids from lives of neglect.

But Beatty believes adoption “is not fair to anyone,” she says. “It’s not fair to the kid because everything is erased, their history is erased. It’s not fair to the adoptive parents, either, because if they’re set up to be saints, which they are, but nobody is, they have to be saints. But they need to be human, and that’s the same with all mothers,” she adds.

“There’s this thing that is placed on all women, that they’re either saints or sinners. Let’s just let people be people with their flaws and their good parts,” Beatty says. “Let’s not make everybody a savior because it’s not real. And especially for an adoptee, you need something that is real because everything real has been taken away from them, and all they have is this lie about how they got there.”