If you’ve heard of Faith Wilding, it’s likely because of her iconic 1972 performance piece “Waiting,” in which she knelt and slowly rocked back and forth as if in prayer while reciting, in four minutes, the first-person story of a woman’s life endlessly held in suspension: “Waiting for my wedding … Waiting for him to give me an orgasm. Waiting for him to come home.” The devastatingly simple work lived on as a widely published text, and was widely performed by others.

Or you might have seen Wilding’s more recent work with subRosa, the internationally known cyberfeminist art collective that explores how women are affected by rapidly changing biological and communications technologies. (Wilding, who lives in Rhode Island and formerly taught at Carnegie Mellon University, co-founded subRosa with Pittsburgh-based artist and educator Hyla Willis.)

But Wilding’s art practice defies easy categorization, so you’ll probably still be surprised by Faith Wilding: Fearful Symmetries, a career-spanning retrospective at CMU’s Miller Gallery. This is the fifth version of this nationally touring show curated by Shannon R. Stratton, of New York’s The Museum of Arts and Design. It focuses on Wilding’s paintings and drawings dating back some 45 years.

The work is, in a word, visionary. Wilding, born in 1943, grew up in a Bruderhof settlement in the jungles of Paraguay. Her formative years in that communal Christian community, and the close proximity to wild nature, affected her deeply, in many ways.

Over two floors of the gallery, Wilding’s 2-D works consistently hark to nature, especially to transformation, or what exhibit materials call “becoming”: the struggling free of a chrysalis, the shedding of flesh, the withering and fall from a high branch.

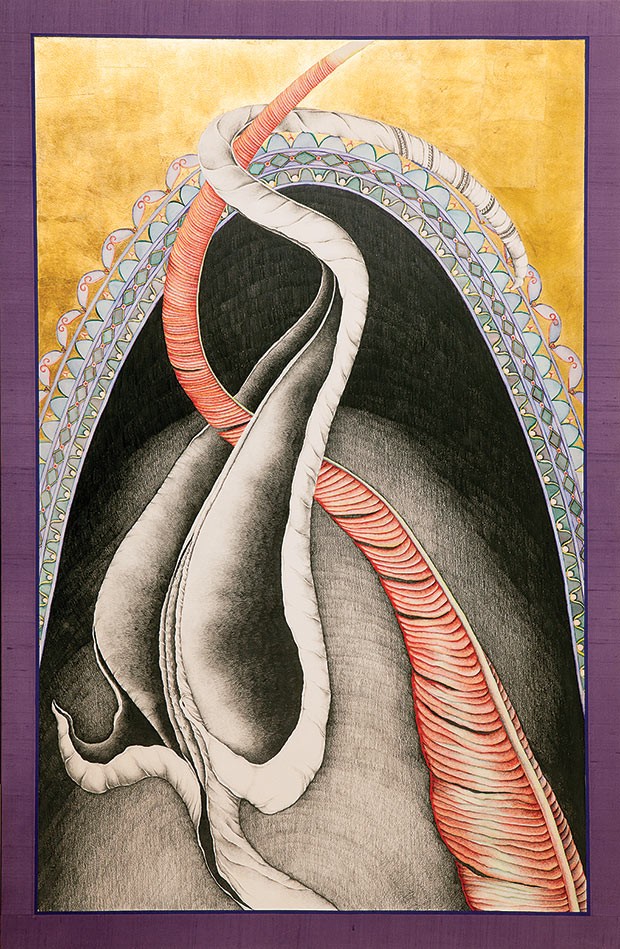

In two gorgeous, large-scale pages from her “Scriptorium” (1983), Wilding employs gouache and watercolor to depict human figures in rapture, peril or transformation, with a repeated shape that might be a chrysalis, maggot, root or mummified person. In the twinned paintings “Ophion” and “Eurynome” (both 1977-78), seed pods rising from a dark hollow split open and twine. Leaves are among Wilding’s most cherished symbols: This big exhibit’s centerpiece might well be the series of six larger-than-life shaped-canvas oil paintings of leaves, hung in the high-ceilinged third-floor gallery. The leaves, more brown than green, are detached from any tree, and dance across the wall, their crisped edges sinuous, alive even in death.

Many of Wilding’s works evoke illuminated manuscripts, blending text with such imagery. Some words are her own lyrical, stream-of-consciousness musings, but Wilding, a prodigious reader, often quotes literary figures. “Tears,” her 2010 series of small watercolors, includes tear-shaped repositories of protean watercolor, tear-shaped hearts, and tear-shaped buds. Quotes are drawn from favorites including Virginia Woolf (“Every time the door opens, I cry ‘More’!”) and Emma Goldman, though William Blake (who of course supplied the exhibit’s title phrase) turns up, too. So much of Fearful Symmetries, like Wilding’s 1976 “Venus leaves” series, seems simply about the effulgence of nature as rendered by her brushes and pen.

Wilding is a noted activist, and those expecting more explicit politics will find it in “The War Room,” a small gallery featuring early-1990s works — including three of her resin-and-vellum “biodresses” — incorporating images of medieval armor to explore how the body is “weaponized by technology, culture and politics.” And indeed, in Fearful Symmetries, Wilding’s politics are typically expressed (as with subRosa) through an engagement with human bodies.

Like “Waiting” (a video of which is included in this exhibit), some statements here are outspokenly feminist. A drawing of a mermaid holding a disembodied uterus and ovaries quotes novelist Angela Carter: “To deny the bankrupt enchantment of the womb is to pare a good deal of the fraudulent magic from the idea of women …”

But most of Wilding’s politics in Fearful Symmetries are existential. “How can the bound body be free?” she asks on a 1976 pencil sketch of leaves twining around themselves. Wilding’s plants often represent people; what binds, often, is convention. “When thinking of breasts, sex no longer worries her, but all femininity concentrated in women, and all masculinity concentrated in men worries her. And how can she live mythless,” reads one “Daily Text” piece from 1988. Wilding remedies the issue herself in the accompanying image of a figure with breasts and male genitalia.

Wilding grounds such discussions in her own experience in 1990’s “untitled (the parents),” which references her Bruderhof upbringing, with its rigid gender roles. In the life-sized watercolor, a “male” undershirt and trousers and a woman’s dress, both empty of bodies, stand flanking the nude (and faceless) figure of a young woman, as if she’s been given only two options. If Wilding faced such a conundrum, she carved her own way out with passionate, sensual art that speaks to the truth of life beyond human society.