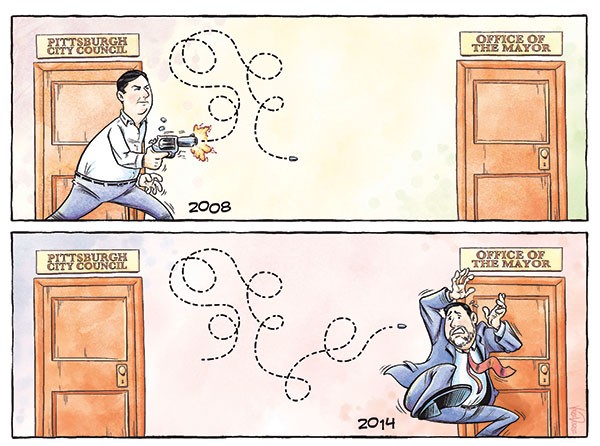

When Bill Peduto talked about fighting crime during his run for mayor last year, he touted a measure he'd supported while on Pittsburgh City Council — a 2008 ordinance requiring gun-owners to report the loss or theft of handguns.

On his campaign website, "Enforcing the Lost and Stolen Gun Laws" was listed as one of Peduto's 100 Policies to Change Pittsburgh, under a section on "Making Our Streets Safe." The law was intended to curtail gun violence by targeting illegal gun-trafficking: Felons who are barred from purchasing guns directly sometimes acquire them through "straw purchasers," who may later claim the gun "disappeared." As the campaign site explained, "Most guns used to commit crimes were purchased legally and were lost or stolen, eventually ending up in the hands of a criminal. If a gun is lost or stolen, the police should be informed. Aggressively implementing this law gives police tools they need to get illegal guns off the streets."

Peduto stood by the bill throughout the campaign. In an April 2013 response to the Pittsburgh Black Political Convention, he wrote, "My first order of business as Mayor will be to fully implement the Lost and Stolen Handguns legislation I authored and passed through Council."

Just days after Peduto was elected mayor in November, he again pledged to enforce the legislation, at a public-action meeting of the Pennsylvania Interfaith Impact Network.

But four months after taking office, no one has been charged under the ordinance. And Peduto tells City Paper that's unlikely to change.

"If we try it, we'll be sued, and under present state law, we will probably lose," Peduto says.

Under the ordinance, individuals who do not report their guns lost or stolen within 24 hours of discovering they are missing can be fined $500 — and $1,000 for each subsequent offense. Peduto wouldn't entirely rule out fining people: The city "may still try to make a couple cases" down the road, he says. But he says his focus will be on replicating an awareness campaign started in Philadelphia — which also has an unenforced lost-and-stolen ordinance on the books — urging gun-owners to report missing firearms.

Critics of Pittsburgh's ordinance, though, say Peduto's shift proves that the bill was never enforceable. Kim Stolfer, chairman of Firearms Owners Against Crime, says the legal landscape hasn't changed since the law was passed, let alone since Peduto's 2013 campaign.

During the debate over passing the bill, says Stolfer, "I said it wouldn't be enforced because it's illegal. ... It's just as illegal today as it was then."

Pittsburgh City Council passed lost-and-stolen legislation in December 2008 by a 6-1 vote. It became law in 2009 but was never signed by then-Mayor Luke Ravenstahl. The law has been in limbo ever since. Ravenstahl didn't enforce it, arguing that Pennsylvania state law prohibits local regulation of legal gun ownership. Nor has the law's constitutionality ever been decided: Courts have held that, until someone is prosecuted under the ordinance, no one has a legal basis for challenging it.

While precise information on current straw purchasers was not available, police say that they come across such cases every year. And Peduto has previously criticized Ravenstahl's inaction: In his letter to the Black Political Assembly, Peduto called the ordinance "yet another piece of legislation that has never been implemented by the current administration."

Some of the ordinance's original supporters, meanwhile, still say it could be a useful tool.

"I think for Pittsburgh and the other places in the Mon Valley having problems with gun violence, they saw this as a reasonable thing to do," says former City Councilor Doug Shields, one of the ordinance's authors. Nor, he says, should the city back down from a court battle.

"If someone wants to bring an action in the court of law, they have every right to do that, and why would you be afraid of that?" Shields says. He argues — as does Peduto — that the ordinance doesn't infringe on the rights of gun-owners because once a gun is lost or stolen, it is no longer in an owner's possession. And he says that although Peduto might want to do some additional analysis before moving ahead, "Nobody should be afraid of enforcing a law. ... We have to enforce the laws that are already on the books."

In the past, Peduto has sounded a similar note. "If we as a city were to be sued by the NRA for enforcing the lost-and-stolen handgun [law], I'd welcome that lawsuit," Peduto said during a January 2013 mayoral debate. "Because if it saved one life, it's worth the dollars of hiring a few lawyers in order to fight it."

But today he says, "I thought a common-sense approach to be able to lessen the amount of violence that's happening throughout the state of Pennsylvania would be welcome in Harrisburg, instead of this ridiculous response that anything that has to do with a gun we must automatically fight."

When asked why the administration has changed its position on what enforcement of the law will look like, spokesperson Tim McNulty said, "What [Peduto is] doing is finding other ways, in the face of an aggressive state law, to reach the same end result," which is to get illegal guns off the streets.

City Council President Bruce Kraus, who also helped author the 2008 legislation, agrees. "I believe that our lost-and-stolen legislation is a common-sense approach to addressing one of the root causes of gun violence," he says, "but the state has effectively kept us and our police from using the crime-fighting tool."

"I'm working with the police and the mayor to do all we can within the state's restrictions," Kraus adds, citing efforts that range "from tracking guns used in crimes to pushing public-education efforts for law-abiding gun owners to self-report when their firearms are lost or stolen."