The rules of traditional keno are simple: A player picks 20 numbers out of a possible 80. The more numbers you hit, the more money you win. And if Gov. Tom Corbett's plan to privatize the state's lottery system goes through, finding a place to play will be easy as well. You'll be able to sit down in front of a video terminal at your favorite bar or restaurant, and play.

But when it comes to gambling, nothing is ever straightforward.

Keno is the linchpin of Corbett's plan to turn over management of the lottery to Camelot Global Services, which runs the United Kingdom's national lottery. Camelot, the sole bidder to compete for the management contract, has pledged to deliver lottery revenues to the state of $34 billion over 20 years — a projection that assumes keno will be legalized statewide.

That may sound like a great deal for the state, and for the senior citizens who depend on government programs supported by lottery proceeds. But it's not necessarily a great deal for players themselves. Experts say the odds in keno favor the house even more than in other games of chance.

"If your goal is to make more revenue off of people playing games in bars, I'd go with keno every day of the week," says Eliot Jacobson, a California-based casino-games analyst.

What's more, worry some observers, the atmosphere of many barrooms isn't conducive to doing the math.

"The technology that supports this game is very high-speed, can lead to very high stakes, and the proximity of these games to alcohol could lead to some bad decisions," says Keith Whyte, executive director for the National Council on Problem Gambling.

Raising concerns even further is the fact that Corbett seems intent on playing cards close to his vest. While the legalization of slots parlors was hotly debated for years, Corbett maintains that he doesn't need legislative approval either to privatize the lottery system or to begin offering keno.

But the stakes are too high for such a move to be made without extensive debate, says Whyte: "There is absolutely a massive need for input on this issue."

State officials say that doubling down on gambling opportunities by adding keno is an easy call.

As the state has looked for better ways to manage the lottery system, one goal was "to learn from the industry how best to prudently increase Lottery revenues," Elizabeth Brassell, press secretary of the state Department of Revenue, told City Paper in a written response to questions. "[I]ndustry bidders unanimously demonstrated that incorporating Internet products and monitor-based games into the Pennsylvania Lottery's portfolio is one of the most effective ways to responsibly grow revenues." Fourteen states already offer keno, she says.

Brassell says the game will be like the state's old Super 7 lottery game, in which players selected 20 numbers out of a possible 80 and the winning numbers were drawn once a week. Keno drawings will be held "more frequently," she acknowledges: Terminals in bars allow players to pick their numbers whenever the state wants to hold a drawing. And although the game's parameters have not yet been set, Brassell notes that "in other states, keno is typically drawn every few minutes throughout the day." Although details of how the machines will be distributed are not yet available, the game will be located in bars and restaurants, much like the lottery vendors on video monitors.

Keno could provide the state with an additional $150 million to $195 million annually. As with existing state lottery games, that money would be earmarked for programs benefiting the elderly.

But for the state to win that money, gamblers have to lose it. And while almost every game of chance favors the house, says Michael Shackleford, from the player's perspective, "Along with slots, keno is the worst choice of any game in a casino."

Shackleford teaches a class on casino math at the University of Nevada Las Vegas; he runs a website titled after his nickname, wizardofodds.com, and has extensively studied casino games.

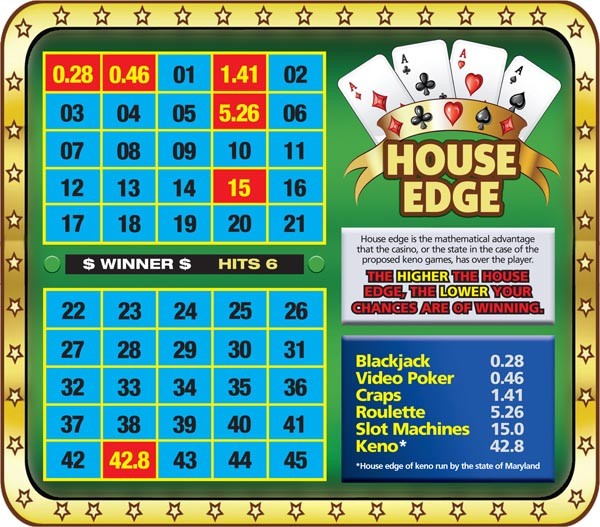

One of the features of his website is the calculation of what is known in gambling as the "house edge": a calculation of just how much the odds favor the house — and thus how much a casino can expect to win on a particular game, or how much the player can expect to lose.

The house edge on keno can fluctuate based depending on how the game is set up. That information for Pennsylvania's proposed system is not yet known. Brassell says Pennsylvania's keno would likely be run similarly to what other states offer. So Shackleford calculated the house edge for the state of Maryland's keno game, one of the country's first. The house edge in that game fluctuates between 38 percent and 50 percent depending on how many numbers a player chooses.

The house edge in keno is very close to the 50 percent house edge for other number-draw lottery games, according to Shackleford. Compared to casino-style games, according to Shackleford's website, keno offers far and away the worst return on your wager: Blackjack has a house edge of .28 percent, video poker has an edge of .46 percent, and craps checks in at 1.41 percent. Even the games considered to have the worst house edge in a casino — roulette (5.2 percent) and slot machines (15 percent) — don't come close to keno.

And losses could escalate quickly, depending on how frequently the state holds drawings. "When you get into these electronic games, you can play a new game almost as fast as it takes to pick your numbers and press a button," Shackleford says.

Jacobson agrees that the odds against winning in keno are especially steep.

"I'm definitely not one of those people that think keno or any form of gambling is evil," says Jacobson, who owns a firm, Jacobson Gaming, which provides mathematical analysis of casino games. "But still you must remember that when it comes to a house advantage, keno is as tough as it gets."

Despite the poor odds, though, Jacobson says people seem to like the game. "I've been in locations in Arizona where the game terminals offer both keno and video poker. Every player that I saw was playing keno even though they had a much worse chance of winning versus video poker."

Keno's appeal is obvious, he says: a high top prize. In the Maryland keno game (which requires 10 numbers matched for the top prize), the jackpot is $100,000. Corbett is being a "pragmatist" by choosing keno over other possible games, he says.

"It's what people want."

Some state legislators, though, aren't so enthusiastic — about either keno or Corbett's plan to privatize the lottery system itself.

Currently the Pennsylvania Lottery is run by a state commission and administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Revenue. It is the largest in the country, and last last year contributed about $1 billion to senior programs.

State Rep. Frank Dermody (D-Cheswick) says the state's lottery system is one of the most efficient in country. And if there is to be an expansion to keno, he says, "we need to study it, look at the research, have public hearings, get information and make sure it makes sense to say, 'Let's just go do it.'"

Likewise, Eugene DePasquale, the state's new auditor general, says the entire process needs more transparency. He says a "shift toward keno" would be a major policy change.

"Even if you think this is a good idea, what are the impacts of keno going to be?" asks DePasqaule. "It needs to be completely vetted and typically that's something that's a natural part of the legislative process, but the governor is trying to circumvent that."

Previous attempts to expand video gambling have floundered in the legislature, in part due to opposition from conservatives in Corbett's own GOP: Many rural politicians cite moral objections to games of chance. During Gov. Ed Rendell's final term, for example, the administration tried to raise education funding by expanding video-poker terminals to bars, restaurants and social clubs. The GOP-controlled legislature roundly defeated him.

Corbett himself has recently said that although he was opposed to video-poker terminals in bars, he supports keno.

What's the difference?

"Keno is just another terminal-based Lottery game," the Department of Revenue's Brassell says, and the state Lottery Commission doesn't need the legislature's permission to roll out new variations of the Daily Number or its scratch-off instant-card games. By contrast, she says, "Video poker is a new form of gaming that would require legislative authorization."

Some observers take issue with such distinctions, noting that keno represents not just a variation on existing games of chance, but a whole new platform for gambling.

"I'm asked all the time if the expansion of gambling has resulted in more people becoming addicted, and that is hard to answer," says Whyte, of the National Council on Problem Gambling. "But what I can say with certainty is that the severity of gambling addiction has gotten worse. And that's because there is so much more access to places to gamble that it makes it harder for an addict to stay clean.

"This is a tough business for governments because this is one of the few products where there is a fundamental conflict of interest," Whyte adds. "They have to maximize profits while at the same time they have a serious obligation to protect the health of [their] citizens. Balancing those economic and ethical obligations is hard."

Bill Kearney, a self-described former gambling addict who is now a Philadelphia-based anti-gambling activist, puts things more succinctly.

"The problem with Tom Corbett is he talks out both sides of his ass," he says. "This is just another addiction for the state coffers to feed off of.

"The thing about Corbett is, he was the attorney general. He handled cases of people embezzling money and stealing money to gamble. He knows what can happen, and he wants to make it even easier for people to get into trouble."