On Nov. 5, Pennsylvanians will vote on a ballot referendum known as Marsy’s Law, which proponents deem a crime-victim rights amendment to the Pennsylvania state constitution. The referendum states the amendment would “grant certain rights to crime victims, including to be treated with fairness, respect, and dignity.”

The law passed unanimously in the state Senate and by a 190-8 margin in the state House. It will only be ratified into the state Constitution with a successful referendum vote by Pennsylvania voters, and then a signature from Gov. Tom Wolf (D-York), who has given Marsy’s Law his endorsement. Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala (D-Fox Chapel) is also in favor of Marsy’s Law, as is the Pennsylvania District Attorneys Association.

One of its most prominent features is ensuring that victims of crimes and their families are provided notification about arrests and legal actions against the victim’s offender. But it’s much more complicated than just that provision. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the League of Women Voters both oppose Marsy’s Law for concerns about how it could infringe on the rights of the accused.

Pennsylvania already has a fairly robust crime-victims protection law on the books, and Marsy’s Law doesn’t involve many changes to that current statute.

With pointed opposition and potential redundancies with existing laws, and despite the surface-level favorability with politicians, how exactly did Marsy's Law constitutional amendment get on this year's ballot?

The answer boils down mostly to one man: Henry Nicholas, a billionaire and founder of the software company Broadcom. Marsy’s Law didn't start and spread with a grassroots movement, but instead with the funding, advocacy, and organization from a small group of wealthy individuals, the Leach family.

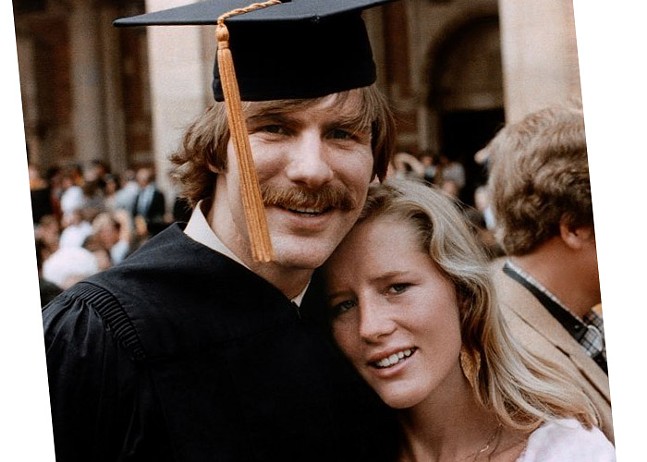

In 1983, 23-year-old Marsalee Ann Nicholas, who went by Marsy, was murdered in Malibu by Kerry Conley, her ex-boyfriend. Conley was convicted of second-degree murder in 1985 and he died in prison in 2007. But in the period between his charges and his conviction, Conley was free after posting a $100,000 bail.

The Leach family consisted of Marcella and Bob Leach, and Henry and Marsy Nicholas, who were Marcella’s children from a previous marriage. In the nearly two years between Conley’s charges and conviction, the Leach family said they often saw Conley in their neighborhood and it was traumatizing for them.

In a 2010 article in the Orange County Register, Nicholas said the first encounter was particularly shocking because the Leach family hadn’t been notified Conley made bail.

“Right after the funeral, my mother was in the supermarket buying a loaf of bread. She went up to the checkout stand and there was my sister’s murderer, staring her down,” said Nicholas to Register columnist Frank Mickadeit. “He would drive around our neighborhood in a convertible, flaunting.”

Nicholas also told the Register that he and his parents would have to drive about four hours to speak at Conley’s parole hearings to make their case that he shouldn't be paroled. Nicholas said on the second parole-hearing trip, his mother had a heart attack from the stress, but survived. He also complained about the temperature while speaking at the parole hearing.

With pointed opposition and potential redundancies with existing laws, and despite the surface-level favorability with politicians, how exactly did Marsy's Law constitutional amendment get on this year's ballot?

tweet this

“It’s 105 degrees and you’re in sitting in a room across the table from this murderer,” said Nicholas in 2010.

That experience led Nicholas and his family to advocate for Marsy’s Law in California, which was passed via a ballot initiative in 2008. Ellen Griffin Dunne, the mother of actress Dominique Dunne who was murdered by an ex-boyfriend in 1982, also got involved in the advocacy for the California push. During the 1990s, the Leach family helmed the group Justice for Homicide Victims, which successfully advocated for several tough-on-crime laws in California, including the state's controversial Three Strikes law which mandated longer prison times for repeat offenders.

But since the late 2000s, advocacy has been mostly efforts led by Nicholas to get Marsy’s Law amended in other state constitutions.

The law has been passed and instituted in about a dozen states so far.

Marsy’s Law for All, the foundation that has the goal to get Marsy’s Law passed in all 50 states and eventually in the U.S. Constitution, was started in 2009 by Nicholas. All of the $6 million raised by the Pennsylvania Marsy’s Law effort (Marsy’s Law for Pennsylvania LLC) has been raised from Nicholas’ foundation. There are no other donors to Marsy’s Law for Pennsylvania LLC, according to state campaign finance files.

This funding dynamic has basically always been the case for Marsy’s Law. According to League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania, more than $102 million has been spent advocating other states to pass the law, and Nicholas has contributed 97 percent.

Interestingly, the millions raised and spent by Nicholas has its own storied past. In 2008, Nicholas and other Broadcom executives were indicted on stock fraud for an alleged scheme where Broadcom misled shareholders about how much it was paying employees by fabricating information about stock options. (Those charges were later dropped). Nicholas also had a drug charge in 2010 that was later dropped, and a drug trafficking charge in 2018, for which he took a plea deal to avoid prison in August 2019.

As of January 2018, it was reported that Nicholas was worth $3.6 billion. Nicholas has given tens of millions to several causes, especially ones with ties to his home region of Orange County, Calif. His philanthropy involves education, technology, the Episcopal Church, national defense, and the arts. But these causes are all overshadowed by his advocacy for Marsy’s Law.

Nevada passed Marsy’s Law in 2018, as did Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina and Oklahoma. According to campaign finance reports, Nicholas, either personally or through his foundation, funded virtually all of the cash for these efforts.

The ACLU says these changes could shift the scales too much in favor of the state, which is responsible for prosecuting the accused in criminal cases.

tweet this

This is one of the reasons the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania is skeptical of Marsy’s law, as well as concerns that the law is just repeating protections that already exists and that, if passed, victims could refuse to be interviewed or to turn over pertinent evidence or testimony.

The Pennsylvania ballot questions states in full: “Shall the Pennsylvania Constitution be amended to grant certain rights to crime victims, including to be treated with fairness, respect and dignity; considering their safety in bail proceedings; timely notice and opportunity to take part in public proceedings; reasonable protection from the accused; right to refuse discovery requests made by the accused; restitution and return of property; proceedings free from delay; and to be informed of these rights, so they can enforce them?”

Both the ACLU of Pennsylvania and the League of Women Voters of Pennsylvania brought a suit against Marsy’s Law on Oct. 11, alleging that the ballot initiative is too broad and should be instead broken up into two or three separate questions.

In the commonwealth, the Pennsylvania Crime Victims Act already affords victim’s protections and established rules that crime victims have to be notified about arrests and legal actions against the victim’s offender, but Marsy’s Law would extend some of those rules to the victim’s family members too.

According to WHYY, the ballot referendum doesn’t change very much about the state’s existing crime-victims protections laws, and really just codifies those laws into the state constitution, making it easier for the victim's and victim’s families to sue if those rights aren’t upheld.

However, Marsy’s law does make some significant changes to rules concerning the accused. One of the more contentious parts of the proposed amendment would allow victims to “refuse an interview, deposition, or other discovery request” made by the accused or the accused’s lawyers.

This is one of the main reasons the ACLU of Pennsylvania opposes Marsy’s Law. The ACLU says these changes could shift the scales too much in favor of the state, which is responsible for prosecuting the accused in criminal cases.

“As a result, many of the provisions in Marsy’s Law could actually strengthen the state’s hand against a defendant, undermining the bedrock legal principles of due process and the presumption of innocence,” wrote Elizabeth Randol, legislative director for ACLU Pennsylvania, in a statement after Marsy’s law cleared the state Senate.

The full text can be read here.

According to WESA, Jennifer Storm of the state’s Office of Victim Advocate and other Marsy’s Law supporters say allowing victims to refuse pretrial discovery is common in Pennsylvania, and so the accused shouldn’t be that impacted.

“As a result, many of the provisions in Marsy’s Law could actually strengthen the state’s hand against a defendant, undermining the bedrock legal principles of due process and the presumption of innocence."

tweet this

Recently, when pre-trial discovery was denied as part of an Allegheny County grand jury indictment (where it’s never allowed), four wrongfully accused teens were held in the Allegheny County for 15 months because the county District Attorney’s office failed to vet their alibis.

Pittsburgh criminal defense attorney Patrick Nightingale tells CP that defense cases are often hamstrung without discovery.

Jennifer Riley, Pennsylvania state director of Marsy's Law, said in a tweet to CP that victims in Pennsylvania "can already refuse pretrial discovery requests made by the accused" and that "with Marsy's Law, the defense remains entitled to everything discoverable." She wrote that the state will still have to respond to discovery requests in criminal cases under Marsy's Law.

On paper, Marsy’s Law appears like an amendment worthy of approval, but opposition has always existed. Several newspaper editorials have been questioning whether Marsy’s law is necessary, including the Palm Beach Post in Florida and Indy Week in North Carolina.

North Dakota passed Marsy’s Law in 2016, but in 2018, North Dakota state Sen. David Hogue said the constitutional amendment didn’t “provide any meaningful protections for victims that isn’t otherwise in our statute,” according to the Grand Forks Herald. He said there were some negative consequences of Marsy’s Law, but added they were manageable but come with “obvious costs.”

Jack McDonald of the North Dakota Newspaper Association said one potential consequence would likely occur when legal challenges come about if someone is hindered in gathering information to defend themselves. Houge noted Marsy’s Law being embedded in the constitution makes it very difficult to undo.

“The problem is when you put it in Constitution, you make it more difficult,” Hogue said to the Herald. “You cannot readily amend or adjust it because it’s embedded within the Constitution.”

Storm said in a tweet to CP that Pennsylvania's version of Marsy's Law could have amendments made to it by the General Assembly, even if passed and the state constitution is changed because there is language in the law says "as defined by the General Assembly."