Picture yourself in a college classroom. While laying out assignments for the week ahead, the professor mentions that an assigned reading contains descriptions of sexual assault. Then a student who has experienced sexual assault expresses gratitude for the heads-up.

This is an example of a trigger warning, and while it might seem simple enough, this kind of practice is at the center of a heated debate about college campuses. Professors and students have been widely criticized for embracing the practice, and it’s been added to the growing list of what critics say is wrong with millennials. But some say the controversy has been exaggerated.

“As soon as we say ‘trigger warnings,’ we’ve invoked like this whole thing about free speech and academic freedom and coddled students, and all these sort of tropes that come to mind. It’s become like a meme,” says Michael Goodhart, a professor of political science at the University of Pittsburgh.

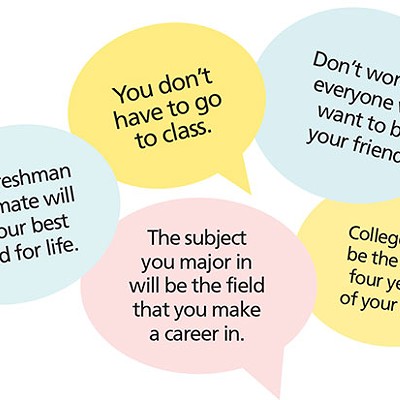

A slew of panicked think-pieces and op-eds about trigger warnings have been produced in the past few years. In 2014, an article in Inside Higher Ed claimed the spread of trigger warnings was having a “chilling effect” in classrooms. In 2015, The Atlantic ran a cover story on the topic titled “The Coddling of the American Mind.” And in the fall of 2016, the University of Chicago’s dean of students sent a letter to the entire incoming freshmen class disparaging the use of triggers warnings on campus.

One case frequently cited in articles criticizing the practice involves students at Rutgers University who requested trigger warnings on Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway because of the suicidal themes. But just how common are trigger warnings on college campuses?

“I think that both the controversy and the assumed prevalence are wildly exaggerated,” says Julie Beaulieu, a gender, sexuality and women’s-studies professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

However, in a survey released in 2016 by NPR, of 829 public- and private-university faculty members around the country, 51 percent responded that they had used trigger warnings, while 49 percent responded that they had not.

And many say trigger warnings have been unfairly demonized by those critical of political correctness and of the censorship of offensive material.

Goodhart believes comparing material that might simply offend someone to material that might traumatize is a false equivalency. “It seems to be the worst kind of denial about the reality of trauma in post-traumatic stress around things like sexual assault, to take one example,” he says.

For a university to dismiss trigger warnings can also seem like a dismissal of mental-health issues. “We cannot claim to take mental health seriously, and then use disparaging or dismissive language when talking about the need for care or reasonable accommodation,” says Beaulieu.

And contrary to popular belief, trigger warnings did not originate in college classrooms, but on micro-blogging platforms like Tumblr, around 2011. The site functions largely without regulations, and users learned to look out for themselves and each other. Posts with traumatizing content, like a picture of self-inflicted cuts, would be tagged (for example, “TW self-harm”), so users could block the posts. When teens who grew up in this environment started going to college, they brought trigger warnings into academia.

“From the opponents, we frequently hear that the young are being coddled, or that certain individuals are restricting rights,” says Beaulieu. “That response seems to misconstrue what people need, which is to be heard, respected and validated when a boundary needs to be set.”