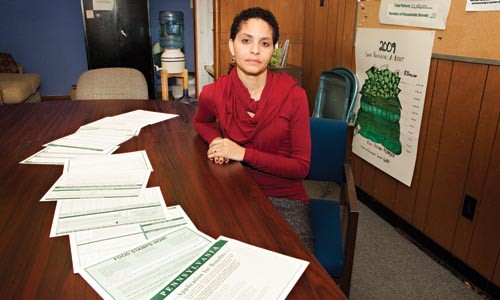

Brighton Heights resident Anita Lawrence-Bandy realized she might be in for a rough patch after losing her job. Times are tough all over. What the 52-year-old didn't realize, however, is how difficult it would be to just get someone from the state Department of Public Welfare to pick up the phone.

Like unemployed people across the state and the country, Lawrence-Bandy turned to food stamps to help pay for groceries while she began searching for work. But when she contacted the state Department of Public Welfare (DPW) to enroll in the program, she found an agency that seemed to be struggling as much as many of its clients.

"You end up leaving messages all the time," Lawrence-Bandy says. "Without that human contact, [you are] just leaving messages. ...You get really frustrated and want to give up."

Advocates for struggling households say DPW clients suffer a litany of problems: Voicemail boxes are often full, and paperwork is sometimes lost. Problems can be exacerbated by a "pool" system in which, rather than dealing with a single caseworker, clients are transferred from one DPW employee to another, having to explain and re-explain their circumstances to each one.

Lawrence-Bandy is far from alone in having to turn to food stamps, a federally funded program now known as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Consider:

* In Allegheny County, food-stamp participation now stands at 153,681 people (more than 12 percent of the county's population), according to Pennsylvania DPW data.

* Statewide, more than 1.6 million people (slightly more than 13 percent of Pennsylvanians) are using food stamps.

Food-stamp participation has increased every single month for almost the past three years in Allegheny County. In November 2007, only 113,374 people were enrolled in the county. Statewide increases have been similarly large.

It shouldn't come as a surprise that more households are receiving assistance during a sharp economic downturn. But as the number of people who use the program has skyrocketed, some advocates for the working poor say the state's system of providing that aid has been overwhelmed. The result: mounting frustration for Lawrence-Bandy and others in the same situation.

"A lot of people are not getting the benefits they should be getting," says Tara Marks, co-director of anti-hunger organization Just Harvest. The DPW is trying to work around the fact that it is understaffed, says Marks. "They need more workers."

Linda Torres, a DPW worker and official for the Pennsylvania Social Services Union-SEIU 668, couldn't agree more. The union represents welfare case workers, and Torres says the department suffers from understaffing and a computer system that is often inadequate to the task.

"You never can trust what the computer tells you," Torres says. For instance, it might tell a case worker a client is not eligible for a certain program even though the client is. Furthermore, not assigning staff to individual clients "just masks the problem" of not having enough staff by passing clients around.

She says case workers are seeing mounting frustration among clients. "We have more security guards in each of the district offices because the people that are coming in now are more upset than we've ever had in the past."

Even before the recession struck, applying for assistance wasn't always easy. Advocates for struggling families say that the barriers can include long waits, varying standards of what documents are needed from one office to another, and large amounts of documentation to qualify for help. The food-stamp program application is 18 pages long.

But with the economic downturn, some Just Harvest clients are saying that the paperwork, once completed, is being lost by the DPW. In other cases, they say they have been notified of an appointment with a case worker after the date of the meeting had passed.

State DPW spokesman Mike Race acknowledges that the heavy caseloads present challenges. Still, he says, the agency "works as quickly as we can to help people get the benefits to which they're entitled." Federal law mandates applications for food stamps be processed within 30 days, and Race says 95 percent of applications DPW receives meet this goal. About two-thirds of the applications, he says, are being processed in seven days.

Still, Race acknowledges that the DPW staff has been under the gun -- and for a long time prior to the current economic downturn. Between 2000 and 2009, he says, overall staffing for the DPW dropped by 3,500 positions, which Race says is "the largest decline in employee [staffing] of any Cabinet-level agency." Nor has the agency's budget increased as greatly as the need. Budget data from the Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center shows that the DPW spent $97 million on personnel costs in the 2007-08 fiscal year. But currently, the agency spends roughly $99 million on staffing.

And there is evidence to suggest that some Pennsylvanians are now falling through the cracks: DPW statistics show that every month, roughly a third of applicants are rejected for not furnishing the required information. Just Harvest co-director Ken Regal says that in some cases, that's because people mail or fax the information to the DPW, and it is lost or misplaced, causing the application to be rejected.

Has the state done anything to deal with the enormous influx of new applicants it has seen in the past several years? Race points to the COMPASS website, which Pennsylvanians can visit to see if they qualify for assistance, and which Race says has helped generate more applications. Hiring more staff is another matter, though. "We have to work within our budget," Race says.

And advocates fear the situation will likely get worse. The same downturn that cost Lawrence-Bandy her job has depressed tax revenues. Partly as a result, Republican Governor-elect Tom Corbett is facing a deficit of roughly $4 billion dollars -- and has pledged not to raise taxes. "I think there is money to be saved across the board" in state agency budgets, he told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette a few weeks after winning the election.

"We're concerned," says Carey Morgan, executive director of the Greater Philadelphia Coalition Against Hunger. "From what we're hearing, the intention is to make substantial cuts."

Marks, of Just Harvest, echoes those worries, expressing fear "that cuts may be made without careful consideration of the consequences. If the incoming governor and legislative leaders really want efficient government ... they should invest in better customer service and improved accuracy for a department whose client base is only growing."

Corbett's office did not respond to City Paper's request for comment.

Pennsylvania isn't alone in trying to cope with an influx of newly needy people applying for assistance, points out Stacy Dean, director of food assistance policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. Nationally, about 42.4 million people -- about one in eight Americans -- are receiving food aid, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That's compared to 27.1 million people in November of 2007.

But Dean says other states have pioneered more comprehensive, paperless systems. In states like Wisconsin, clients can do more over the phone, or have documents scanned and e-mailed to state workers. As a result, the applications can be easily tracked and followed up.

Dean is sympathetic to state agencies struggling with the problem. "[They] have absorbed 14 million people [nationally] since the beginning of the recession," she says. "We all need to recognize state systems are stressed right now."