It's late August, 92 degrees and muggy -- the dog days of summer. Not that Hobo seems particularly enthused about it: The dog won't venture past the doorstep onto the sizzling alley. Instead, he sticks close to the side of Eric Graf, owner of Blackberry Studios and principal architect of the local rock supergroup, The 9th Ward of which Hobo is an occasional member.

Even without the heat, the scene beyond Graf's door isn't particularly inviting, apart from a crop of tall corn soaking up the blinding rays. This isn't the Lawrenceville of little boutiques and hipster bars -- it's the Lawrenceville of used-car lots, Section 8 housing and sometimes-grim urban realities. Since Graf moved in a little over a year ago, a man was shot in the stomach right on Blackberry Way; nearby, a single heroin bust recovered $13,000 in cash. Down the street, 19-year-old Jayla Brown died tragically just weeks before, a bystander shot outside another Lawrenceville recording studio, the hip hop-oriented I.D. Labs.

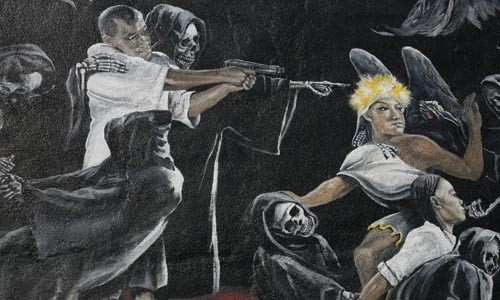

This is the Lawrenceville depicted in the apocalyptic mural dominating the exterior of Blackberry Studios. Painted by Mark Runco, the mural is based on the Book of Revelation, depicting Satan battling the Archangel Michael for the souls of ordinary people as they struggle with vice and corruption. Although this scene is set over the Red Sea, in many ways it's really based on these streets: The neighborhood's actual residents modeled for the human figures, and their surroundings inspired the dark imagery.

This is also the Lawrenceville Graf has tried to portray in The 9th Ward's fusion of blues, classic rock and punk. The band's debut album begins by chronicling the neighborhood's attributes, good and bad, in a desperate high-speed rant called "Birdies on the Wire."

"We got hookers, we got hangers, we got lookers, we got bangers / We got choppers we got peepers, we got losers we got keepers," Graf yells over the distorted groove, before emcee Steph Wilson steps in for a verse: "We got abandon homes, we got abandon kids / We got the beautiful-ist city for a place to live ..."

"I wanted the record to sound rougher," says Graf of The 9th Ward's self-titled album. "It's not a timid sound -- that's one thing I can say about it. It's a big, boss sound." Starting with "Birdies on the Wire," he says, the album traces an arc from dark to light as it describes the immediate surroundings in realistic detail -- which makes lyrics like "She's her own woman now, she's got the bruises to prove it" all the more troubling.

"It's not an easy place," Graf admits. "Nobody really knows what's gonna happen down here, really. There's tons of great intentions, everybody has good intentions, but right now there's this uneasiness between people really struggling to make ends meet, and an older class, and a newer class of people who want to come in and totally transform the neighborhood. It's gonna create conflict -- it exists, it has to." But, he adds, "You've got all kinds of things mixing up down here. And I think that's cool; I think it's amazing."

As Graf sits in the doorway with Hobo, young Hussein and several other smiling Somali children stop to chat. They politely decline Graf's offer of a game of street soccer, and Graf has to use his one Somali phrase -- which translates as "no dog!" -- to remind the littlest that his mom doesn't want him playing with Hobo.

If Somali children and tall corn seem a bit incongruous in Blackberry Way, so does Graf, and the glossy olive Jeep SUV he parks there. After all, this is a guy who taught English at North Allegheny High School for 11 years, and had a long successful run with his group Boxstep, touring the world playing music. But now he's "the first white guy on the block," in a section of Lawrenceville where, according to the last Census, the median household income was $24,488 a year -- less than two-thirds of the region's average.

Some might see Graf's presence here as an effort to exploit the neighborhood artistically or commercially, as he seems well aware. "If this business ever really takes off, or the studio or anything, I want to be seen as someone that is a good corporate citizen," he says. "I don't want to just dip into the neighborhood, like 'Oh wow, this neighborhood's crazy, I'm gonna make a bunch [of art] about that.'"

One way Graf has nurtured both his studio business and a growing music community in this struggling working-class neighborhood is by getting to know his neighbors -- friendly Pittsburghers like Hussein -- and by making that doorway separating the studio from the street more of a permeable membrane than a barrier, a point of fluid interaction between the studio, the community, and the band.

Inside the studio, and seemingly oblivious to the August heat, Graf makes espresso over a gas burner in the large kitchen, where a monitor displays the view from a security camera in the alley. "I just wanna see who's knocking on my door," Graf says.

Like the rest of Blackberry Studios, the room's raw, improvisational construction and eccentric furnishings give even the kitchen a sense of boyish adventure: You could be in the belly of a pirate ship, or in a remote mountain fortress. Scrounged wooden bleacher seats from Construction Junction form the ceiling over the control room; a narrow spiral staircase -- designed "more for sexy women" than an average-sized male, Graf notes wryly -- leads to the treehouse-like upstairs. Books line several of the walls, a reminder of Graf's literary background.

Graf sets the espresso on a rustic wood table, the grain so close and dark it's almost black. "It's virgin Pennsylvania timber," he explains. "I almost can't believe James left it."

"James" is James O'Toole, the architect and sculptor who previously used this space as a sculpture studio. When he sold it to Graf in spring 2006 -- reportedly as the result of a dream he had -- O'Toole provided detailed plans for further construction that would turn the building into a combination recording studio and living space: the ultimate musician's clubhouse.

Graf soon set to work on O'Toole's plans with the help of friends including Kristan Ealy, who helped manage the studio and create its distinctive atmosphere early on, and Will Dyar, a well-known musician who's played in the Skinks and Oakley Hall and who is, fortunately for Graf, a carpenter.

They didn't know it at the time, but as Graf and Dyar were building the studio, they were also building a band. Around 3 p.m. each day, they'd trade their hammers for drums and guitar; many of the songs and recordings they did became the basis for the 9th Ward's album. "When you have power tools around all day, maybe that's why the music is so loud," Graf jokes.

One by one, the other musicians trickled in, forming what's now a kind of rotating Pittsburgh indie-rock All-Stars.

"Whoever came down there got to be in the band," says David Bernabo, the group's keyboard player and Graf's longtime musical partner, and former student. "The 9th Ward is kind of a living-out-your-rock-dreams kind of band," he adds with a laugh -- the band's classic-rock attitude contrasts with his own more esoteric output in various mediums. "It's pretty dirty music, and there's elements of hip hop and rock, and the lyrics deal with the neighborhood," he says, adding, "You know, for better or worse." Speaking most directly to the neighborhood, perhaps, are guest spots on the album for Blackberry Way residents.

While initially the band's name reflected the studio's location and where Dyer and Graf both lived, it's not entirely literal. "I called it the 9th Ward 'cause I was watching football being played up in the park," says Graf. "And there was a dad, he had a coach's jacket on -- one of those old mid-'80s kinda satiny ones -- and it said '9th Ward.' I was like, 'That's pretty cool.'"

Also drawn into The 9th Ward's musical vortex have been teen-age guitar whiz Jake Johnson, from Wexford, and underground musicians including drummer Steve Gardner and bassist Dan Tomko, of The 1984 and Ludlow. The album features guest spots from the likes of Centipede E'est's Sam Pace and Sam Matthews of The Bumps, Devilish Merry and Feral Family; the acoustic blues "O-I-L-L-I-A-R Hey Hey" centers around an electrifying harmonica solo from Modey Lemon drummer Paul Quattrone, who sometimes drums with the band live.

Several visual artists have also entered The 9th Ward's orbit, creating the band's album art, video and posters: Mike Budai, Greg Karkowsky, Adam Grossi and Glen Johnston. "It wasn't just like, 'OK Glen, now I have a rock band, and now you need to do the CD art,'" says Graf. "Glen was coming through all the time here, in and around the studio. We all talked about it collectively, like, 'Hmm, OK, this is more about a commentary about all kinds of different things that confront cities.'"

"It's definitely branching out into all the different mini-scenes in Pittsburgh," says Bernabo, of both the band and perhaps its most central member, the studio itself. "A lot of folks are recording down there, and it's becoming kind of like the central hub for a lot of people to work out of, or to meet other people through it."

If this is all starting to sound like a utopian artist's collective, make no mistake: What goes on in Blackberry Way is business, and though musicians have made their way into the band and the studio "from the flow of life," as Graf says, the flow of cash also helped a bit.

"The lines have been pretty blurry between who's here for what," he says. "I had had a couple of opportunities come my way, money-wise ... and the people who've worked with me through either The 9th Ward this year or some of my commercial projects or whatever that I was able to get going, they at least got paid something for their time. And some made pretty good money." Contracts to make music for commercials for things like PA Cyber School and children's programs provided the revenue and the bait to get The 9th Ward off the ground. Emcee Steph Wilson, for example, ended up on the album's opening track ... after coming in to record a children's rap about the letter M.

"I didn't work full time that year," says Bernabo, who lives a short walk away, in Bloomfield. "So I'd go down in the morning, and we'd bang out some stuff for commercials or the children's show we're working on, and then I would work for two hours on my stuff and two hours on Eric's stuff. It kinda grew into everyone working on each other's projects around that point.

"We did 20, 30 [commercial] songs, and I met Will and a bunch of other people through that. That's definitely how a lot of us met, and I guess that's really where The 9th Ward started." Even the band's approach to gigs is more businesslike than many Pittsburgh groups: "I call up the guys and I say, 'Here's the dollar amount that we're being offered, and this is what everybody can get paid if we choose to do it,'" says Graf. If the group decides to play, they hold just one quick practice beforehand. "I don't want to burden people down with, 'Wednesday night is practice night!' I'm not doing that anymore," he explains. "And because I've chosen talented people, most talented people have more than one iron in the fire."

Because while Graf is determined to keep his projects creative and fun, he's also committed to keeping the band afloat -- and the studio booked out at $25 an hour (a bargain rate next to comparable studios in town). He recently moved his personal life into another home he's purchased, to free the upstairs for studio office space and additional production work.

On a given day, the sheer number of people operating out of Blackberry Studios is a little mind-boggling. Regular producers doing work out the studio include Kwan Semley and DJ Detonate; hip-hop producer Tremaine is currently working on tracks with Hill District rapper M-Sceazy. Recent projects at the studio have included everything from hard-edged rapper Cynik Lethal to the gentle alt-country of Boca Chica, from the metalcore band Ludlow to Bernabo's jazz- and folk-inflected solo album, Assembly. Meanwhile, Omar-Abdul (an occasional CP contributor) is putting the finishing touches on his new mixtape.

"The music keeps getting in the way," jokes Sam Matthews, who manages the studio's business affairs. The 49-year-old multi-instrumentalist has been a mainstay of Pittsburgh's DIY and punk scenes since the late 1970s, while also working in advertising and media, and as a producer and project manager. "I've always hung out with artists and done music," Matthews says, "but I've been able to stay organized." Initially, he managed The 9th Ward; now he's helping Blackberry Studios develop its business plan, and reaching out to more commercial work and grant money.

If they're off to a good start, Matthews says, it's in part due to the inexpensiveness and convenience of this still relatively undeveloped part of Lawrenceville. He and his partner recently bought a house nearby. Yet, he acknowledges, "If you want to say we're a collective of Lawrenceville artists, you have to give something back to the community."

"The 4800 block of Blackberry Way has been a challenge, ever since I've been in Lawrenceville United," says Tony Ceoffe, the community organization's no-nonsense executive director and a life-long Lawrenceville resident. "What you have is just like six Section 8 houses there, or substandard houses there, and it's just a pocket of poverty, and it never spins out of that. Because every time we get a good tenant back in there, who might be taking advantage of the Section 8 program, they can't wait to get out of there, 'cause there's two or three other bad families back there that cause all kinda shit."

In such a context, Ceoffe is pleased that Graf moved in, and notes signs of change in the alley. "Over the past several months it's been more quality-of-life type issues -- it's trash, debris -- not so much the more dangerous stuff that was there prior to this summer."

But while Blackberry Studios may be a quirky and charming addition -- and the people who run and frequent it pleasant, hard-working and armed with good intentions -- planting a business like this in the middle of a neighborhood of low-income families and run-down properties raises the specter of gentrification. Purposefully or not, are Graf, Matthews and other fixer-uppers the "urban pioneers" in an economic process that will ultimately displace current residents?

"We're not trying to displace anybody here. We just came here, and whatever will be will be," says Graf, shrugging. Staring into the dregs of his espresso, he looks tired for the first time this afternoon. "This neighborhood still has a long hard climb -- long hard climb."

So far, Blackberry Studio's presence has led to positive, tangible results, says Ceoffe. During the recent Community Cleanup Day, Graf "came up with an idea that if we could get eight or 10 of the kids in the alleyway to help clean up the alleyway, take a little bit of pride in where they lived at, that he would go ahead and allow the kids to come into the studio for eight hours for completing that task," says Ceoffe. "He probably had eight kids back there that busted their ass for most of the day, cleaning up, and they did a wonderful job."

"We work within the community -- we're not really pushing anybody out," says Kwan Semley. A musician and producer who works out of Blackberry Studios, Semley recently moved to Lawrenceville from the North Side; he grew up in New York City. "It's not like we're a realty company which is changing living situations," he says. On a positive side, he adds, "we're working with a couple of kids in here right now, trying to show them the equipment, so they're at least acclimated to it. That's like jobs, prospects, furthering the knowledge they've got."

On the surface, what became the Blackberry Way Community Cleanup Day Mixtape benefited everyone: a cleaner environment for everyone on the block, a creative activity for ambitious young musicians, and, for Graf, a little face-time with his neighbors -- never a bad policy for a visible business in a rough area. "When we did the Community Cleanup Day, and I showed up over at Tony's with a bunch of kids from my block ... [it showed] the neighborhood that we're here as a business, and you're our neighbors too, and we can work together on things," says Graf.

For budding neighborhood emcees like 17-year-old Chris Wagner, a.k.a. Chasm, the offer of studio time for doing the Community Cleanup Day was attractive. After moving to Blackberry Way last December, he hoped to continue the recordings he'd begun in Cincinnati. But although Wagner lives just across the street from the studio, it seems like a different world, at least when viewed through his expectations.

"When you go over there, it's a long process," he says of the studio, his frustration evident. "I can't even get [my music] promoted -- I've got it on the CD, that's not the problem, but I want people to know who I am though, me and my brother, and everybody else who goes over there."

Part of the tension may arise from the fact that studio producers Tremaine and DJ Detonate want to use the studio to do some positive "pro bono" work for the community, as Graf puts it. What Wagner seems to want, though, is a record label -- one that doesn't attempt to change his message. Although he gets along with DJ Detonate, "They tell me, 'rap about the struggle,' but I rap what I feel like rapping about," he says. "I want to be positive and negative. ... [Y]ou could make a couple club songs, then you could rap about somebody being killed or something, but it's like a movie though, you know what I'm saying?"

Despite such disconnects, when the topic of the neighborhood's kids come up, Graf brightens visibly. "The younger kids, this place is a curious wonder to them," he says. "It's got this artwork on the side, it's got this artwork on the front now. I throw out chalk or paints if I have it, or flowerpots to paint, whatever I happen to have that day. They did some clay work one day. For them, it's just something to do in the summer months before they go back to school." He pauses. "And it just so happened that I played soccer in college, and there's a bunch of Somali kids that like to play soccer" -- he laughs -- "so just play with them."

While giving the neighborhood kids something positive to focus on for a few hours is a good start, Graf is trying to make a more lasting impact. If he can obtain funding, he hopes to purchase supplies and hire a teacher to run a twice-weekly art program out of the studio. And those dreams aren't just pie-in-the-sky, says Ceoffe.

"We're hoping that we get more people like [Graf] that are involved, where we can give them a stipend of our money out of the 'seeding' part of 'Weed and Seed' to do programs just like this," says Ceoffe. He's referring to the federal grant Lawrenceville won last year, which will pump roughly $1 million into the neighborhood over five years.

Half of that government money is earmarked for additional, targeted policing in Lawrenceville, he says; the other half goes to community-based activities for young people, "not just music, but also the artists in the neighborhood, and those other kind of literacy-building-type activities." He notes additional projects underway, including DJ training by the Boys & Girls Club, a local potter offering a pottery camp to students with good grades, and activities involving Lawrenceville history.

"We want things that are going to have a lasting effect on a kid," Ceoffe says. And while Graf hasn't received any outside funding thus far, Ceoffe hopes he'll apply this September for a grant to cover art supplies and other costs. "It's not meant for a struggling artist to make a couple bucks for himself, but it can facilitate a business that is doing some work." (Graf says the studio is currently pursuing some funding options including the Weed and Seed grant; he and Matthews don't want to discuss those plans until they've developed.)

Back in Blackberry Studio's control room, a man's voice comes through the monitors. It's an African religious song, followed by an explanation in heavily accented English: "We could sing that song, but it means that Jesus, God, is my dad, or is my father, and Jesus is my savior. When Satan sees him, he trembles and he cries tears nonstop. When he sees Jesus in me, he starts shivering, he can't even stand it, and is like, 'Oh, I lost him, I can't handle this!'"

The man on the recording is a Ugandan minister named John Baptist Mugabi, who lives just down the street. He continues, "So we sung that song ... and everything was just breaking down. Salvation was dancing and dancing and dancing ..." The minister's voice begins to fade, gradually replaced by the gospel-tinged blues rock of The 9th Ward -- it's the intro to the album's scorching final track, "It's Alright."

"We buy our dreams sight unseen / There's no returning / when Rome is burning to the ground," Graf sings in his insistent, Dylanesque cadence. "We pay for losses, we bear our crosses / What goes around is coming on back around."

For the last half-hour, Graf has sat behind the mixing desk, playing educational songs, his own music, Tremaine's work with M-Sceazy that seems destined for WAMO and recordings Omar-Abdul made the night before -- all with apparently equal enthusiasm. But "It's Alright" is obviously an important song to him. He beams with pride as he cues up a version The 9th Ward performed on the 'DVE Morning Show, where he urged the band to stretch the song past 7 minutes, to soak up as much air time as possible.

The WDVE version is dirty, ferocious rock, with soulful guest vocals from two Aliquippa women, Lydia Barnett and Harriett Washington. As they sing and improvise on the refrain, the song builds toward a religious ecstasy: "It's alright, it's alright, it's a-gonna be fine." The volume's almost painfully loud, but as Jake Johnson's lead guitar tears into another extended solo, it's hard not to picture the mural on the side of the studio, that very literal depiction of sin, salvation -- and the surrounding neighborhood.

Just then, Graf turns away from the mixing board and shouts to me over the blare of the speakers:

"I think this band sounds like this neighborhood!"

The 9th Ward, perform at the Ellsworth Street Fair. 9:30 p.m., Sat., Sept. 15. Ellsworth St., Shadyside. Free.