Sixty years ago this week, Pittsburgh artist Andy Warhol began his ascent to stardom.

On July 9, 1962, at his first solo Pop Art exhibition, Warhol unveiled his soup can paintings at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. It came with mixed emotions. He was disappointed that he couldn’t show the paintings in New York. But, after two years of struggling to get a serious gallery to recognize his fine artwork, he was excited to show his work in California because he loved movie stars. Inside the Ferus Gallery, Warhol’s 32 Campbell’s Soup paintings lined the gallery’s walls on shelves rather than hung on the wall. Each 20-inch by 16-inch painting featured a different flavor of soup — chicken noodle, green pea, tomato — meticulously crafted with hand painting, tracing, and rubber stamps for the label’s fleur de lis.

The paintings attracted attention, not all of it positive — but it turned out to be a pivotal moment in the artist’s career.

Writing about Warhol’s 1962 show, a Los Angeles Times reviewer called him “either a soft-headed fool or a hard-headed charlatan.” Another L.A. Times writer complained of “seeing perhaps more paintings of soup cans than one might care to see.” A neighboring rival gallery bought actual soup cans and stacked them in their front window with a sign reading, “Do Not Be Misled. Get the original.”

“A lot of the public thought it was a big joke, like ‘ha-ha-ha what nonsense,’ but Andy’s point, which was brilliant, was always that he wanted to paint a lot of the things we took for granted that were in our everyday lives,” says Richard Polsky, of Richard Polsky Art Authentication, who has written two books on Warhol and the art market. “That was the whole point of Pop Art.”

It’s hard to imagine in 2022 just how radical these Pop Art paintings were, Polsky says. In the early 1960s, he continues, few people collected what we now call contemporary art. Collectors valued Impressionism. Edgier collectors in that era purchased abstract expressionist works by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, or Mark Rothko.

Campbell’s itself supposedly sent a lawyer to the gallery after word spread about the paintings. “The lawyer came back kind of stumped, like most people were at the time, being like, ‘I don’t see any problems. It’s just a painted version of our soup can,’” he reported, according to what Campbell Soup Company Corporate Archivist Scott Hearn has heard. The lawyer wasn’t the only one who was baffled by the bold Pop Art concept.

The paintings were on sale for $200 each, and just a handful sold during the Ferus Gallery show. But the gallery’s director, Irving Blum, so adored the paintings he asked the buyers to return their purchases, so he could keep all 32 together. He convinced every buyer — even actor Dennis Hopper — and persuaded Warhol to sell them to him at a discounted rate of around $1,000 total, though Warhol wasn’t happy about the deal. At least that’s how one telling of the story goes, Polsky says, adding that we’ll never know exactly what really happened.

Even if the exhibition wasn’t a money-maker, the controversy drew debate and helped launch Warhol to fame. By the fall, he was selected for a group show with other emerging artists in New York, then scored his first major solo show in New York at the Stable Gallery, where he presented his Marilyn Monroe paintings. The gallery promoted the show by handing out tiny Campbell’s Soup buttons.

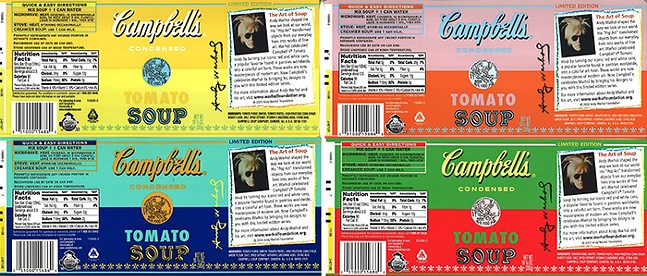

Another indicator of his quick success: By 1964, Campbell’s — once stumped by the concept — commissioned a tomato soup can artwork for a retiring executive. The company paid Warhol $2,000 for the work, though the retiree wasn’t impressed, Hearn says, adding that he’s never been able to track down that particular piece. By 1967, Campbell’s was selling Souper Dresses, patterned paper-like garments with the soup can design that sell for thousands on eBay today.

The meaning of the soup cans has been debated ever since that first show. One theory is that the cans are a portrait of American democracy, says John Zinsser, an artist who teaches a class on Warhol at The New School in New York City. Each can is different, but they’re all soup on the inside, just like each person in the U.S. is different, but they’re all American at their core. The soup cans also speak to the idea of populist products, Zinsser adds. The Queen drinks the same Coca-Cola as everybody else; Campbell’s soup is the same in the White House as it is in your pantry. They’re “iconic monuments to shared ideals,” Zinsser adds, “where high culture meets popular culture.”

Or, each can presents a metaphorical human body with fragile skin (the paper label), skeleton (the metal can), and squishy innards (the soup), posits Kristina Olson, who teaches “The Art of Andy Warhol” at West Virginia University.

Or maybe Warhol just really liked soup, the experts agree. With Warhol’s guarded, beguiling public persona it was impossible to tell if he was putting you on, says Polsky, who met Warhol in the ’80s.

In 1985, Campbell’s continued to commission Warhol for work, including a design for the company’s new soup and recipe mix. After Warhol’s death in 1987, Campbell’s donated to a scholarship in his name. When Hearn, Campbell’s archivist, ponders the artwork’s meaning, he reminds himself of Warhol’s background in advertising before his Pop Art career. He was someone who could see art even in a white-and-red label dating back to 1898. “He showed us the art of our own label,” Hearn says.

Eventually, Blum sold the set to New York City’s Museum of Modern Art in 1996 for a reported $15 million (considered a partial gift) where they draw crowds on par with Monet’s Water Lilies and Van Gogh’s Starry Night. Inside MOMA, Warhol’s series of 32 soup cans has become “like a national monument in the same way people would want to have their picture taken at Mount Rushmore,” Zinsser says. Parents snap photos of their kids with the paintings and millennials hold their iPhones just so for the perfect Instagram photo. Some museumgoers comment on the images — “Who knew there were all those different soups?!” “What’s your favorite?”; others breeze past, seemingly uninterested in the depiction of items they could as easily survey on a grocery store shelf. As they have for the past 60 years, these paintings spur debate: Incisive fine art or vapid, unimaginative copies?

Today, the series is valued at more than $200 million, Polsky estimates. Warhol was fascinated by the alchemy that turned a 19-cent soup can into a painting, a commodity to sell for much more than the original object, Olson says. So it’s ironic — or maybe intentional — that his soup cans, the literal picture of consumerism, inspire more consumption today in the form of kitsch. MOMA’s gift shop sells soup can magnets, puzzles, notebooks, sticky notes, bookmarks, and prints. A search on Etsy brings up pillows, skateboards, crocheted keychains, and stickers inspired by Warhol’s soup cans. Now, everybody can have a Warhol soup can. Maybe that’s a tribute to the artist or maybe it’s an infatuation with consumerism — or perhaps, as Warhol may have intended, those have come to be one and the same.

A Pittsburgh-area native living in New York, Rossilynne Skena Culgan is a journalist whose writing can be found in Saveur Magazine, Atlas Obscura, Thrillist, Google Arts & Culture, and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. She’s the author of the travel guidebook “100 Things to Do in Pittsburgh Before You Die” and is currently writing a Pittsburgh history book. Follow her on Twitter @rossilynne.