It’s Oct. 1, barely one week since Juanda Burton-Burch ended chemotherapy for stage-four colon cancer. But already, the 79-year-old matriarch is bound to a hospital bed, unable to eat or talk.

In four days she will be dead.

One of Burton-Burch’s daughters, Michelle Burton Brown, says visitors have been cycling in and out of her mother’s Hill District apartment on a consistent loop. And when City Paper visited, at least one neighbor stopped by to wish her well. A delivery man dropped off what might have been her last medicine prescription. Medical equipment whirred in the background.

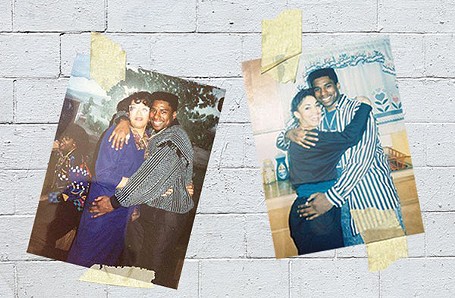

But one important visitor was absent: Burton-Burch’s 48-year-old son, Shawn Burton.

Burton has spent the past 20 years in state correctional institutions, more than 50 miles from his mother, sister and five other siblings. He’s serving life without parole for a 1993 jailhouse murder he claims he did not commit. Not only that, it’s a crime that others, including the man who actually confessed to the killing, say Burton didn’t commit.

“It’s been extremely difficult, especially knowing that he didn’t commit the crime. We know that our brother has been wrongly convicted,” says Burton Brown. “Once you’ve been wrongly incarcerated, it’s just an uphill battle to clear your name.”

Burton was charged with and convicted of the 1993 first-degree murder of Seth Floyd, a California native who was awaiting trial on burglary and robbery charges. Floyd’s death, which was originally ruled a suicide, was the first homicide ever in the Allegheny County Jail.

Burton has maintained his innocence from the start, filing a series of petitions and appeals for the past two decades. In 2013, he got a break when another man confessed to the murder.

But that confession hasn’t meant freedom for Burton. He’s spent the last two years petitioning the court for a new hearing to examine the new evidence. And while the Superior Court ruled in August that he deserves a new trial, Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala has appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

“To do over 20 years for a crime you didn’t commit has got to be the most desperate feeling,” Burton Brown says. “To work on something for 20 years and to get so close, [only] to have the powers-that-be constantly appealing you and fighting you at every angle.

“I’m confident they were hoping he would become tired or depressed and just not fight anymore, but this is his life. He’s been working on this for the past 20 years, and he’s very close to freedom.”

Whether or not Burton is innocent, taking his case as far as he has while acting as his own lawyer is an amazing feat, say legal experts who aid and study the efforts of the wrongly convicted. Post-conviction law is a difficult area to tackle, they say, even for lawyers with years of education.

“These things are incredibly complicated, and for Mr. Burton to have gotten that far is extraordinary,” says Marissa Boyers Bluestine, legal director for the Pennsylvania Innocence Project. “That takes an incredible amount of due diligence on his part. The pitfalls are immeasurable; it’s quite comparable to walking through a field of landmines. To get as far as he’s gotten is almost unheard of.”

Burton’s legal prowess, however, is of little solace to Burton Brown and her family, who had hoped he would’ve been able to be reunited with their mother before she died. Still, she takes comfort in believing that he will soon be free.

“He and his mother made peace years ago. He has nothing to regret in terms of his love for his mother and her love for him,” Burton Brown says. “I know she really had hoped to hold her son in her arms one last time, but I think now she can rest in peace knowing that he will be free.”

The question of Shawn Burton’s innocence was decided long ago for Burton Brown, who says she can still remember her brother mouthing the words “I did not kill your son” to the victim’s mother in the courtroom during his trial.

“My brother is free. It’s simply that the Allegheny County District Attorney’s office has to accept that. My brother did not commit the crime. That’s the bottom line,” Burton Brown says. “It doesn’t take but a couple months to convict someone, to sentence them to life in prison, but apparently it takes over 20 years to clear that person’s name.

“Certainly there’s a flaw in the system.”

When he was first found dead in his cell, on March 9, 1993, Seth Floyd was hanging from the top bunk by his shoelaces and a cord. His death was ruled a suicide, according to media reports from the time. Floyd’s family didn’t believe the finding and asked for a second autopsy to be performed by former Allegheny County coroner Cyril Wecht, who ultimately determined that Floyd had been strangled to death, making his death a homicide.

CP was able to retrieve details about the murder that officials say Burton committed through witness statements and a court brief filed by him and the DA’s office during the long appeals process. According to court records, Burton was in the Allegheny County Jail in 1993 after being arrested for possession of a controlled substance. CP was making arrangements to visit Burton in prison but details could not be finalized by press time.

During the trial, witnesses testified that they had heard that Burton and another man, Melvin Goodwine, were going to murder Floyd because of a family-related dispute between Goodwine and Floyd. Several witnesses testified that they saw Burton and Goodwine in the victim’s cell around the time of the murder.

“[Inmate Marvin Harper] likewise testified that as he walked past a cell, he heard scuffling inside and witnessed two men, whom he positively identified as [Burton] and Goodwine, wrestling another man, whom he did not know, on a bed,” the Allegheny County District Attorney’s office wrote in an appellate brief. “He said the man he did not know was positioned face-down on the bunk and it appeared that he was trying to force his way up from the bed. He said that when he walked past the cell a second time, the three men were still inside.”

Burton was convicted of first-degree murder and received life without parole. Goodwine was acquitted of murder, but found guilty of conspiracy. He received a 5- to 10-year sentence.

But in 2013, Brown received a letter from the Pennsylvania Innocence Project saying that Goodwine had written an affidavit confessing to the killing. Goodwine had written the confession in a 2009 motion to expunge his criminal record.

“[I] committed this act in self-defense. However, I was advised not to use this defense at trial,” Goodwine wrote in the motion. “The petitioner has already admitted to the parole board that I committed this act on my own in self-defense. [I] also [admit] and [take] full responsibility and ownership that an innocent man went to jail for a crime that I committed.”

Burton has filed a number of appeals and petitions over the years, but his most recent application for post-conviction relief was based on Goodwine’s statement. However, in 2013, Common Pleas Court Judge Donna Jo McDaniel, who presided over Burton and Goodwine’s case in 1993, denied the petition because under state law, a request for post-conviction relief must be filed within 60 days of discovery. And while Burton filed his motion within 60 days of being told about Goodwine’s affidavit in 2013, McDaniel ruled that it would have been discovered in 2009 if Burton had done his due diligence.

Burton appealed McDaniel’s decision to the Pennsylvania Superior Court, where six judges voted to reverse her ruling in August 2015. In the majority’s decision, the judges said that although Burton did not discover the confession until four years after it was entered into the public record, his level of due diligence was adequate for an inmate representing himself.

“It would not be reasonable to expect [Burton] to investigate public records with sufficient regularity to ascertain quickly whether Goodwine may have disclosed potentially exculpatory information concerning [Burton’s] case,” they wrote.

“What the court says in this opinion is that you can’t hold an inmate to the same standard as someone who’s not in prison,” says Boyers Bluestine, of the Innocence Project. “And you have to consider the fact that he is in prison without resources. It’s very easy to say, ‘You were convicted 15 years ago, why did it take you 13 years to find this guy?’

“But just because there’s a period of time where it appears nothing happened doesn’t mean that he wasn’t actually working on it. So, to overcome that kind of presumption of lack of diligence because of mere passage of time is very important.”

Three judges disagreed, saying: “Goodwine’s acquittal gave him license to make exculpatory disclosures without risk of criminal prosecution. Combining [Burton’s] awareness of this fact with the precise factual posture of this case, Goodwine was the most, if not the sole, promising source of exculpatory evidence supportive of [Burton’s] innocence claim. This considerably narrowed the scope of [Burton’s] information search from the ‘entirety of the public domain’ to the criminal docket filings of his former criminal confederate, Goodwine.”

On Sept. 11, Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala appealed the Superior Court’s ruling to the Supreme Court on the same basis. A spokesman declined to comment on or respond to written questions about the case because it was still going through the appeals process. But in its appeal, the DA’s office continues the argument started by McDaniel that Burton did not meet the requirement of due diligence.

“Where the newly discovered fact is a matter of public record, the Majority now allows a pro se petitioner (and not those represented by counsel) to obtain a hearing without having to plead and prove due diligence,” the DA’s office said in its filing. “This exception, however, directly conflicts with this Court’s long-standing precedent that matters of public record cannot be ‘unknown’ for purposes of the after-discovered facts exception to the timeliness requirements of [state law].”

Burton Brown claims that the DA’s appeal is an attempt to hide evidence of misconduct in its office.

“How long is it going to take for Allegheny County to accept that they cannot suppress this information?” Burton Brown says. “Once it’s opened, a lot of things are going to come up. People have written affidavits to the effect that they were offered deals or less time, things that were inappropriate and will reflect poorly on Allegheny County.”

Burton is referencing a February 2014 affidavit where the now-deceased Marvin Harpool says he provided testimony against Burton in exchange for favor. In the original trial and court documents Harpool was referred to as Marvin Harper, one of the witnesses who said he saw Burton and Goodwine in Floyd’s cell. CP specifically asked the DA’s office in writing whether it had investigated allegations that witnesses were offered favors for testimony against Burton.

According to the Innocence Project, informants and incentivized witnesses providing false testimony contributed to wrongful convictions in 19 percent of the 1,600 cases of exoneration nationwide since 1989.

In the affidavit, Harpool wrote:

“I, Marvin Harpool, was 19 years old in 1993 and in the old county jail at the time when Mr. Shawn Burton was a suspect in a jailhouse homicide, this particular homicide was not witnessed by me. I was informed by the county jail guards that if anyone would be willing to provide any information which would link to Mr. Burton to this homicide that I could receive legal favor in exchange for this information.

“I did notify the prison guards that I had actually witnessed Mr. Burton commit the particular homicide, in exchanged [sic] for my $50,000 bond to be dropped and that I could gain my freedom. I was informed by the Allegheny County Jail guards that the bond deal had been approved by the District Attorney, at which time I gave a false statement to the District Attorney and the Courts also that I had actually witnessed the homicide.”

Harpool also wrote: “I also hope and pray that the Burton family will also forgive me for what I have done to their loved one.”

Even if the Supreme Court rules in Burton’s favor, it doesn’t necessarily mean that he will be freed immediately. It only means that there is enough new evidence to suggest that a new trial is warranted. That’s an idea that Burton Brown can’t believe the DA’s office won’t acknowledge.

“I think it’s disingenuous when people won’t even entertain the idea that maybe they made a mistake, and continue to use all the powers of the court, the county and the system to fight one single incarcerated man who is doing legal work from his jail cell without a lawyer,” says Burton Brown. “It’s like David and Goliath. My brother Shawn has a rock, and they have the whole power of the system behind them: lawyers, advisers, money, clout, influence, status …”

And the fact that Burton has spent the majority of the last 20 years fighting for his release on his own is what makes his case so significant, advocates for the wrongfully convicted say.

“You do it all on your own, without access to the Internet, without access to up-to-date case law, without resources to hire an investigator,” says Boyers Bluestine from the Pennsylvania Innocence Project. “And those are just some of the obstacles in your way. That’s assuming you’re literate and have some access to some resources.”

“The law is very stacked against inmates. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court has said that finality trumps everything, even in light of potential innocence claims,” Boyers Bluestine continues. “My understanding is that Mr. Burton has claimed his innocence for a very, very long time. Courts get kind of almost deaf to claims of innocence … so the fact that he has been able to do this is just an incredible testament to him and the work that he’s put in.”

Now Burton’s case is in the hands of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The court must first decide whether to hear the case. If the justices choose not to, the Superior Court’s decision to grant Burton an evidentiary hearing will stand. If they do decide to hear the case, Burton will face yet another legal battle.

“We’re requiring inmates who really have no experience at all, no knowledge of the system, no education, no expertise; we expect them to navigate this on their own. It’s kind of insane,” Boyers Bluestine says. “We’re making this so difficult for people. When we continue to put these restrictions on them again and again, the only thing that we do is cut off people who are actually innocent from being heard. That’s all these procedural barriers do.”

And what happens if Burton does finally win his plea to retry his case? Both the district attorney’s office and the defense will have to track down witnesses to a more than 20-year-old murder.

“Under the best of circumstances, these are all difficult cases,” says John Rago, a law professor at Duquesne University. “You’re dealing with witnesses that are 20 years old[er], witnesses whose memories no doubt have been lost or exaggerated or falsified. We know enough about memory science that just to try a case alone on memories that go back 20 years would be a very difficult thing. And that’s if you can find them.”

And what would overturning Burton’s first-degree murder conviction mean? His conviction for conspiracy in the murder could still stand, but his co-defendant Goodwine was sentenced to 5 to 10 years for conspiracy.

“If everything alleged is true, he has served more than twice the time of the actual killer in this case,” says Rago. “That’s the irony.”