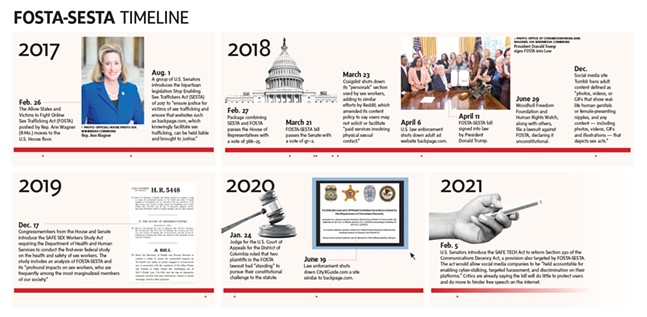

But time has shown that the legislation — a combination of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act (FOSTA) and the Senate’s Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) — has actually done little to combat the problem. Additionally, it’s being used as a tool to target sex workers by subjecting them to overpolicing, limiting their ability to work, and, in many cases, silencing them altogether.

Sex worker advocates believe problems of FOSTA-SESTA go even further, citing instances where law enforcement has blamed the bill for making their jobs more difficult, as sex traffickers have only gone deeper underground and into darker corners of the internet. Advocates also believe the bill has opened the floodgates for lawmakers to impose more restrictions on free speech online, not just for sex workers, but for everyone.

As a result, FOSTA-SESTA has inspired a movement with sex workers speaking out and demanding protections, and that their industry be decriminalized. This includes Pittsburgh, where, despite the city’s fairly conservative veneer, is still home to people providing a variety of services to clients, from full-service sex work to phone sex and camming.

Pittsburgh City Paper spoke to various local sex workers to understand how the city fits into what has become a national and, in many cases international problem, as the bill has created a ripple effect into other countries. They described how FOSTA-SESTA changed both their online and in-person communities and their ability to work safely, all while some law enforcement agents have argued the bill actually impedes their ability to crack down on sex trafficking.

Not long after FOSTA-SESTA became law, the Pittsburgh chapter of the Sex Worker Outreach Project was formed. SWOP PGH is part of a national network using education and activism to end the stigma against sex work. Co-founded by Jessie and PJ Sage, and Moriah Ella Mason, the volunteer-run group has gone on to become one of the most prominent voices for Pittsburgh-area sex workers.

“I would say that the passage of FOSTA-SESTA turned my world upside down,” says Jessie Sage, who worked as a sex columnist for City Paper and Pittsburgh Current before stepping away to focus on writing a book. “It made sex work less safe, especially for the most marginalized sex workers, and deplatformed all of us.”

As a result, Jessie and PJ devoted much of their time to sex work organizing. While Jessie no longer runs SWOP PGH, she and PJ still extensively cover the issue through writing, research, and their Pittsburgh-based podcast Peepshow.

Adrie Rose identifies as a full-service sex worker, and has made sex work the focus of her graduate study research, mainly looking at how websites and financial institutions deal with sex workers. She says FOSTA-SESTA has contributed to breaking down support systems central to sex workers, and not just online. This includes sex workers referring clients to each other, which Rose says is “crucial when you don't want to get arrested, or you're trying to stay alive.”

“The simple act of sharing information with another escort can get you charged with facilitation, which is a felony,” says Rose, who has stopped doing sex work during the pandemic due to health concerns. Under FOSTA-SESTA, she says giving client referrals, money, or even car rides to other sex workers qualifies as trafficking. “So not only did it really erode the way that we exist online, but it's eradicating our ability to create communities.”

PJ Sage echoes Rose, adding that FOSTA-SESTA has hit the sex work community hard, with many losing online accounts and access to payment methods, or being shadowbanned, a term referring to when content is hidden from internet searches.

“Not only is it harder to advertise, our political speech is being suppressed,” says PJ, who also researches sex work as a visiting instructor in Gender, Sexuality, and Women's Studies at the University of Pittsburgh. “It's become harder and harder to communicate and organize with folks in our community. Our posts are constantly taken down. … It's difficult to simply exist online.”

Rose adds that FOSTA-SESTA has also made relations between law enforcement and sex workers worse. “And already, the police were not really in our corner,” says Rose. “They weren't advocating for us, they weren't protecting us.”

In June 2018, Trib Live and other outlets reported that police officers in Allegheny County had been taking sex workers into custody for the first-degree misdemeanor charge of possessing “instruments of a crime,” in this case, condoms. Reports showed that in 2017, Allegheny County Police had charged people with both prostitution — a third-degree misdemeanor — and possessing an instrument of crime in 100 cases. In 15 of those cases, condoms were the alleged instrument of crime. Not long after the news came out, the county police announced they would no longer charge sex workers for posessing condoms.

Many advocates view this type of policing as overreaching and unconstitutional, and Rose claims tactics employed by police on sex workers can be even worse than the reported overcharging.

“Something that no one ever talks about is that, during vice investigations, the police are allowed or even encouraged to pay for sex, have sex with sex workers, and then arrest them,” says Rose. “That's rape by deception.”

Rose and others point out that FOSTA-SESTA has made things worse for sex workers in other ways too, especially for marginalized groups. Rose, who is Black, says people of color, especially trans women of color, have always been more targeted by law enforcement.

She adds that technology plays a big role in persecuting marginalized sex workers, especially as websites and social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr have been swift to ban certain posts and users under FOSTA-SESTA.

“It has become something of an issue where social media sites use algorithms and automated systems to go after sexually explicit content,” says Rose. “A lot of algorithms are already biased because the people that created them are biased. ... Content moderation is always going to go after marginalized people.”

But some are trying to use technology to benefit sex workers. Lena Chen is a Chinese American performance artist and writer who serves on the SWOP PGH steering committee. She and fellow artist Maggie Oates have been developing a video game called Only Bans, a play on the popular adult video platform OnlyFans. The game, which is being featured this month as part of Kelly Strayhorn Theater’s Freshworks creative residency, is described on the theater’s website as a “digital performance work” that “critically examines the policing of marginalized bodies and sexual labor to empathetically teach people about discrimination faced by sex workers on the Internet.”

Chen, a sex worker and MFA candidate at the Carnegie Mellon School of Art, believes her work could help educate people about the realities of sex work, as well as the implications of FOSTA-SESTA for those working in other arenas.

“It’s more about telling people’s stories,” says Chen. “I’ve participated in a lot of collaborative art projects with other sex workers and sex worker collectives that have to do with the experience of trying to work online in the post-FOSTA-SESTA environment, which is quite hostile, not just to the sex workers, but also to artists who are dealing with nudity or sexuality, or activists who are dealing with issues of gender or sexual violence.”

Chen also became a fixture at Pittsburgh anti-Asian hate rallies in the wake of the Atlanta spa shootings, which has led many Asian American women to speak out on how they are often seen as objects of fetishization. Chen says this is not uncommon to sex work.

While sex trafficking remains a problem that needs to be addressed, FOSTA-SESTA may not be the best way to tackle the issue, a theory already being observed by law enforcement. Since its passing, police departments and agencies across the country have expressed frustration with how the law has actually made it more difficult for them to identify and arrest sex traffickers, as the adult sites the law targeted, primarily backpage.com, served as a way to track them. In a story by WRTV Indianopolis from July 2018, a vice cop said his department had been “blinded” by the loss of backpage, saying the site was a valuable tool to “trap” sex traffickers and pimps.

Instead, critics say the legislation has only served to chill free expression by using sex trafficking as a “boogeyman,” as Rose calls it, to pressure websites into banning users over fears of being shut down. Rose says much of this is due to the spread of misinformation over how sex trafficking works and how it targets victims, which then casts sex workers as a victim or facilitator of sex trafficking.

She says viewing sex workers as victims who need to be saved is part of the problem, as many enjoy what they do and view it as a valuable service. There’s also the issue of how sex work is defined, with many not recognizing that even the act of watching pornography or going to a strip club qualifies as supporting sex work.

To combat this, advocates are emphasizing the humanity of sex workers. Chen says when she worked as a stripper at a club in Downtown Pittsburgh, she and many of her co-workers were students who saw the work as an opportunity to make a lot of money.

Jessie and PJ Sage do this by working together as a married couple, demonstrating that people in the sex work industry have stable relationships and families. “I think all sex workers challenge stereotypes simply by not being one-dimensional tropes,” says PJ.

Jessie Sage says that, in the midst of these crackdowns and harsh penalties, FOSTA-SESTA “does absolutely nothing to protect victims of sex trafficking.”

“It is important to recognize that the law itself doesn't offer any funding or resources, it is strictly punitive,” says Jessie, adding that it's driven by morality, and more concerned with policing the internet and banning pornography under the guise of helping trafficking victims. “By and large, it is an anti-sex work agenda, not an anti-trafficking agenda.”

In a July 2020 article from WHYY, former sex trafficking victim and advocate Melanie Thompson still supports FOSTA-SESTA through the criticism and argued it will help out an end to “an oppressive system that thrives off of other oppressive systems, namely misogyny, patriarchy, and capitalism.”

On a Pennsylvania level, state Rep. Summer Lee (D-Swissvale) proposed legislation that would decriminalize sex work in Pennsylvania. Introduced in October 2020, the legislation, which Lee created with help of sex worker advocates, is believed to be the first of its kind in the state General Assembly’s history.

“We can no longer ignore the fact that sex work is work, however stigmatized – and that sex workers deserve the same protections as other workers,” Lee said in a press release. “As legislators, it is our duty to serve all of our constituents to the best of our ability, regardless of which profession they are in.”

Until real policy change occurs, however, activists are working together with organizations to better aid sex workers in this dangerous time. SWOP PGH member Nicole Gallagher says the organization has been partnering with Planned Parenthood of Western Pennsylvania and others to deliver safe, welcoming health care and resources to sex workers.

PJ Sage says people should also support organizations working in the sex worker community, naming SWOP PGH and Planned Parenthood of Western Pennsylvania, as well as TransYOUniting and SisTers PGH.

Rose believes that, no matter what, those creating the laws affecting sex workers should actually listen to the people in the community about what they need.

“Part of the issue is that people who don’t know what they’re talking about are doing the most talking,” says Rose. “They’re talking over people with the lived experiences and with the actual knowledge.”