Artist Greer Lankton's final work, the dioramic piece It's all about ME, Not You, was first exhibited at the Mattress Factory in 1996, just a few months before she died. Since the piece became a permanent fixture at the museum in 2009, the museum has built a kind of shrine around the artist, exhibiting sketches, sculptures, journal entries, and other pieces of her work and life.

To give museum-goers a more intimate look at her life, and to celebrate the transgender artist during Pride Month, the Mattress Factory will hold Greer Lankton on Film, an event screening home videos of Lankton in childhood and as a young adult. The collection of 11 films will be on display June 4-9 in the museum's lobby with a special event on June 6 featuring Margery King, curator of the Greer Lankton Archive Exhibition.

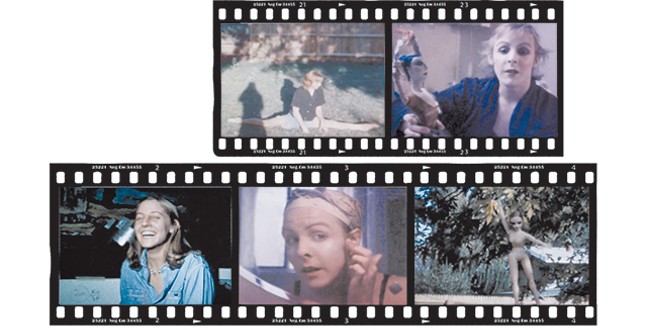

The films, made in the mid-’70s, were donated to the Mattress Factory in May 2018 by Lankton’s lifelong friend, Joyce Randall Senechal, who came to visit the museum last year along with some of Lankton’s family to see the archives they’d donated on display. The Super 8 films were digitized, and after they’re screened this week, Mattress Factory archivist Sarah Hallett hopes to make them viewable for the public online as part of a larger project to digitize Lankton’s archives.

The films are short, most of them around or under three minutes and without sound, though the longest is around 15 minutes long with sound. They offer brief glimpses into Lankton's life and work throughout the years, from early sculpture and stop-motion work to pondering her gender expression and transition, to opening presents on Christmas morning with her family. The clips were not filmed with the intention of public viewing – many of the clips are dark and hazy – but they nonetheless evoke many of the themes found in Lankton's archive.

There are repeated images and scenes in the films that are reflected in much of Lankton’s work. Many of the films, which are mostly unlabeled, feature dolls in some form or another. Oftentimes, the dolls perform stop-motion ballet, or are contorted into splits, cartwheels, and other acrobatics. Most of the dolls are naked, though some show them undressing, one item of clothing at a time. Some of the films are intriguingly vulgar, like the one that features a doll giving birth to three armless, legless babies. As is common in Lankton's work, there is thoughtfulness and sadness but also a weird and surreal humor.

In one of the films, the only one with sound, Lankton talks at length, while putting on her makeup in the mirror, about her feelings on gender and her decision to transition. “I can’t stand being a boy, it’s such a bore,” she says. In the same film, Lankton holds up one of her dolls, this one lightly clothed with a heavy face of makeup, and explains some of her fixation with them. “I realized when I first started making [dolls] that the thing I was doing was making these women, when in reality what I wanted to do was make myself into a woman,” she says. “The dolls just became more and more of a refinement of what I wanted for myself … there’s so much beauty in being a woman that I wanna be. It’s just something I want.”

There’s uncanniness to watching someone explain themselves to you so long after they’ve died, and to see their work transition from childhood fun to a fixture in a museum. Lankton likely never imagined that these home movies would be something for public viewing, but they’re a posthumous gift. It’s a joy to hear her talk and see her smile and better know the artist who left so much behind to be admired.