Remember the UPMC advertisements that used to claim the health-care giant was "not a business" but "a collection of people, and surprises and ideas you weren't expecting"?

Apparently, it's not even that much. In a Jan. 3 filing to the National Labor Relations Board, the nonprofit health-care giant — routinely identified as the region's largest employer — claims it actually has no employees at all.

"UPMC is a holding company, which holds certain ownership interest in other entities. UPMC has such directors and officers as are legally required to maintain its corporate existence, but has no employees," UPMC attorney Thomas Smock wrote in a motion asking that a pending NLRB complaint be dismissed against the company.

"UPMC conducts no operations," the filing adds. And it "engages in no employee or industrial relations activities."

UPMC's filing was a response to a 30-page complaint the NLRB filed in December, alleging that a unionization effort was being unfairly blocked by UPMC, as well as by managers at Magee Women's Hospital, UPMC Presbyterian and UPMC Shadyside. Workers at those facilities began discussing joining the Service Employees International Union in January 2011, but said UPMC management went above and beyond to block their attempts to unionize.

For example, the complaint alleges that UPMC "engaged in surveillance of its employees who were engaged in union activities," "interrogated employees concerning their union activities and/or the union activities of other employees," and "promised employees increased benefits and improved terms and conditions of employment if they refrained from union organizational activity." Another allegation involves a supervisor at Presbyterian Hospital directing employees to "call the police and not let union supporters and organizers into employees' homes." Another claim alleged that employees "were not allowed to solicit for the union at other employees' homes while off-duty."

In other instances employees were told that talking about the union at work was a violation of the company solicitation policy, and other employees were issued verbal and written reprimands, suspensions and terminations.

For its part, UPMC, Presbyterian, Shadyside and Magee hospitals have denied the allegations in separate filings before the NLRB.

The NLRB's complaint consolidates those allegations across the various facilities, making an umbrella complaint against "UPMC and its subsidiaries." The agency plans to hold a hearing on them on Tue., Feb. 5. But UPMC's filing seeks to remove "allegations ... that UPMC is a single employer" with the hospitals.

As UPMC's motion notes, Magee has its own board of directors; another board governs both Shadyside and Presbyterian hospitals. And each of those boards, the motion says, "maintain[s] its own personnel policies and conduct[s] its own employee discipline activities, all without input from UPMC." UPMC's motion, in fact, seeks to remove only the corporate entity from the NLRB complaint, not the individual hospitals. UPMC and each hospital filed its own answers to the complaint — denying all claims. But each filing was very similar to the other and all were signed and submitted by attorney Thomas Smock of the law firm Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak & Stewart.

The motion does acknowledge that UPMC "owns 100 percent" of the hospitals. And there is overlap between UPMC's board of directors and the governing bodies of each hospital. Even so, the complaint asserts, UPMC "does not involve itself in the day-to-day operations" of the facilities.

UPMC did not return calls or an email for comment on its filing. But attorneys for the SEIU reject those claims, and at least one labor-law professor is baffled by them.

"It seems to me that the attorneys here wasted UPMC's money" by asking a judge to simply toss out the complaints against it, says Anne Lofaso, a labor-law professor at the West Virginia University School of Law. Lofaso is also a former NLRB attorney, and says, "I have personally never seen a judge grant a motion for summary judgment like this before a hearing."

Who actually calls the shots in an organization like UPMC is the kind of question that gets determined at trial, when testimony and other evidence can establish who bears responsibility for personnel decisions. "There is an employer here," says Lofaso. "Somebody employs these workers and if you say that's not you, then that's something to be decided at trial."

UPMC did submit one piece of evidence for its claim: a sworn statement from Michele Jegasothy, UPMC's corporate secretary. Jegaothy's statement simply restates the assertions made in the complaint — that UPMC "conducts no operations" and "does not employ any person mentioned" in the NLRB complaint, and so on.

That's not good enough, says Lofaso. "Say UPMC is just a holding company, fine, but you have to prove that at trial. You have to do more than just produce an affidavit from a company employee."

Attorneys for both the union and the NLRB are already challenging UPMC's claims. They note that the holding company admits to fully owning the hospitals, and that there are numerous ties between the board of UPMC itself, and the boards of individual hospitals. (To take just one example, UPMC Executive Vice President Elizabeth Concordia sits on Magee's board of directors.)

"One-third of the votes of UPMC's Board of Directors are held by individuals appointed by or historically involved in the governance of the subsidiary hospitals," writes Claudia Davidson, an attorney for SEIU Healthcare Pennsylvania. "Thus, many of the same individuals oversee the management of and set policy for both UPMC and the subsidiary hospitals."

What's more, Davidson argues, UPMC and its hospitals also file joint tax returns.

Davidson writes: "Certain of UPMC's subsidiaries, including UPMC Presbyterian Shadyside and Magee-Women's Hospital of UPMC, no longer file separate tax returns and instead report their activities to the IRS together with UPMC's activities, on a ‘group return.'"

In lieu of paying taxes like private businesses, nonprofits file a Form 990, which breaks down the organization's revenues and expenditures. Prior to 2006, Davidson writes, "UPMC and each of its tax-exempt subsidiaries were separately recognized by the IRS," but later on, "UPMC and its subsidiaries were permitted to file a group return after the IRS reviewed the relationship between UPMC and its subsidiaries and determined that they were entitled to a group exemption." And in its Form 990, Davidson writes, UPMC describes its hospital network as "functionally integrated" while billing itself as "the parent organization of a large integrated healthcare delivery system consisting of controlled subsidiaries."

But if anything will have Pittsburghers confused about UPMC's legal argument, it's probably the commercials. For years, UPMC has used ad campaigns and other media to build a brand identity. And it's still doing so today.

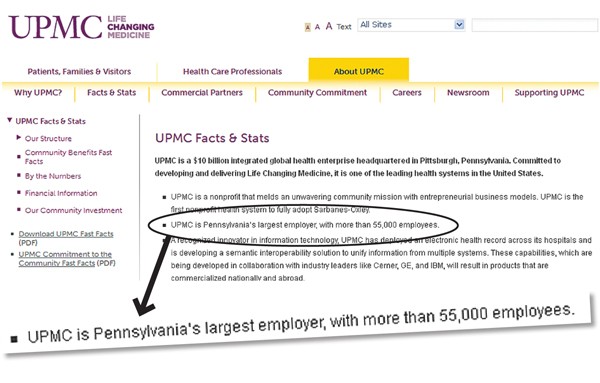

At a UPMC.com web page explaining "Our Structure at UPMC," the nonprofit claims to be "more than a network of hospitals. We are 55,000 individuals whose compassion and care reach far beyond our hospitals' walls." Elsewhere online — on a page titled "UPMC Facts & Stats" — the site boasts "UPMC is Pennsylvania's largest employer, with more than 55,000 employees."

Meanwhile, in a UPMC-produced video entitled "Pittsburgh: A New Vision, A New Tomorrow," CEO Jeffrey Romoff seems to know enough about personnel policies to describe which employees will be successful.

"The person who succeeds at UPMC has fire in his belly; is committed; is energetic; is desirous of being better tomorrow at what he does — or what she does — than he is today," Romoff says into the camera. "What UPMC nurtures is creative talent on the part of very, very creative people and allowing them to blossom and to grow."

UPMC has spent years "branding the heck out of themselves to make money," says Barney Oursler, executive director for Pittsburgh United, a local social-justice group that has been calling on UPMC to "pay its fair share" of local taxes, and to not interfere with unionization efforts. "But when the time comes to take responsibility for its actions," says Oursler, "they say, ‘Oh, we don't exist.'"

"It's a shell game," Oursler adds. "They are who they want to be in order to serve their own best interests at the time. They're proud to say it's their people who make them who they are — right up until it's time to treat those people fairly. If it wasn't so sad, it would be laughable."

Lofaso, the West Virginia University professor, says after the hearing, the hearing judge will make a recommendation to the NLRB. Based on that ruling, the agency will make a decision and, if necessary, levy punishment.

If UPMC loses, it can appeal the case through the federal courts. But Lofaso says it would be a mistake to press the arguments in its complaint if a judge tosses them out: Claiming "that ‘we don't exist and we don't have employees' is probably going to end up pissing off the court."