At the beginning of jury selection in a sexual-assault trial, many prosecutors have been known to give the following instructions to potential jurors:

“Look at the person next to you and tell them about your most recent sexual experience,” he or she will say.

The potential jurors often stare aghast or even gasp before the prosecutor tells them they don’t actually have to share such a personal experience with a stranger. But, the prosecutor says, that’s exactly what the alleged victim in this trial will be asked to do.

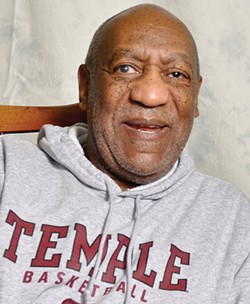

Next week, jurors for the Bill Cosby sexual-assault trial will be selected right here in Allegheny County. Cosby is being tried for the alleged sexual assault of Andrea Constand, a former Temple University employee. The woman claims Cosby, a Temple alum and then-member of the school’s board of trustees, drugged and sexually assaulted her at his mansion in Elkins Park, Pa., in 2004. (City Paper does not typically print the names of alleged sexual-assault victims, however, Constand has spoken out publicly in this case.)

From start to finish, sexual-assault cases are some of the most sensitive tried in court. In sexual-assault trials, jurors come to the courtroom with a set of preconceived notions, and it’s up to legal teams to uncover them in an effort to ensure the case is not hampered by sexual-assault biases. But uncovering these biases presents its own set of problems for potential jurors as the process can be traumatic for those still coming to terms with their own experiences with sexual assault. And, ultimately, according to research into sexual-assault cases, biases are often unavoidable: In cases like Cosby’s, jurors are more likely to base their verdict on what they bring to the courtroom, not what they learn once they’re there.

“It’s going to be a very complex jury selection,” says Jeffery Frederick, director of jury-research services for National Legal Research Group, Inc. “You have the nature of the case being a he said/she said case, and people’s experiences with sexual assault and rape, not only their own, but people they know. You have Mr. Cosby as a public figure who has taken a great hit on his reputation, but there are still people who are great fans. There’s a lot of different issues that are floating around here.”

The jury-selection process isn’t like picking teams in gym class. Legal teams don’t select the jurors they want; they can only exclude jurors from sitting in a trial. The prosecution and defense each has a set number of preemptory challenges, which can be used for any reason, and an unlimited number of challenges for cause, that are decided by the presiding judge.

In order to decide which jurors to exclude, the legal teams conduct a process called voir dire, a preliminary examination that examines a juror’s background and attitudes toward the case. This is especially important in this case because sexual-assault accusations against Cosby have been at the center of media attention for years.

“For either side, what you’re trying to do is, you’re trying to understand the opinions, viewpoints and motivations of the potential jurors you face,” says Frederick. “In this case there’s a number of avenues you have to consider. One is the substantial publicity of this case and all the information that’s been out there. Some of this information is inadmissible. For example, the 59 or 58 people who claim they have been sexually assaulted by Mr. Cosby, that is not relevant to this case. But the fact that there are indications of other alleged victims, you’ll have issues with that and whether jurors can set that aside.”

Nowadays, some jury analysis is conducted behind the scenes by analysts who pore over a potential juror’s Facebook page. According to Frederick, 70 to 80 percent of people have Facebook pages, and thanks to the social-media site’s interface that allows users to respond to posts with emojis, analysts can uncover how jurors feel about certain topics.

“You’d have to look at stories and articles related to Cosby on Facebook and look at the comments people have made. You go through to make sure none of the jurors that have come up have expressed their emotions on these posts,” says Frederick. “You want to see if they have certain likes that would indicate that they’d be more receptive to government or the defense. And there are actual Facebook pages that are pro- and anti-Cosby.”

Uncovering the biases of potential jurors is especially important in sexual-assault cases, says Lynn Hecht Schafran, director of the National Judicial Education Program.

“People come into court with a mental script of what rape is. Rape is a stranger who jumps from the bushes with a knife and there’s a woman walking alone late at night in a provocative dress,” Schafran says. “That’s 180 degrees from reality. The reality is that the vast majority of rapes are committed by someone the victim knows, indoors. It has nothing to do with the clothing you’re wearing. There are no weapons involved. You have to get jurors to give up their script and listen to the evidence presented.”

The biases jurors bring to sexual-assault trials are especially important in those cases involving scenarios that mirror the Cosby case, where the defendant is known to the victim. And according to research, the preconceived notions jurors have about these kinds of incidents can often determine the verdict in these cases, regardless of the facts presented during the trial.

In the 1960s, Philadelphia researchers Harry Kalven and Hans Zeisel observed jury deliberations and surveyed judges in 3,576 criminal jury trials. In approximately 25 percent of the cases, they found, the jury and judge disagreed on the verdict.