The cops outside Club Zoo in the Strip District say kids in face paint have been waiting for the place to open since morning. When the doors finally open at 7 that evening, the liquid that's confiscated most often isn't bottom-shelf vodka; it's Faygo, a Detroit brand of pop. Today, it's more like holy water. Though it's getting tossed into giant trashcans, inside it will flow. And flow, and flow.

The kids are juggalos -- devotees in the cult of Insane Clown Posse, a pair of white-boy rappers from suburban Detroit who've earned hero status with self-identified outcasts the world over through hyper-violent lyrics and over-the-top stage shows. Pittsburgh is a juggalo hotbed, including an annual mass visit to Kennywood Park.

The group's status comes despite -- or maybe because of -- receiving almost no video airplay and almost no major-label backing. ICP fans say they are united by their outsider status and loving acceptance of one another. They call their fandom a family, which manifests itself in signoffs on e-mails and Internet postings: MMFCL, or Much Muthafuckin' Clown Love.

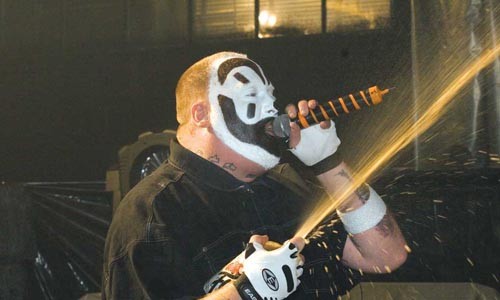

Family members are easy to pick out at ICP shows. Lots of fans ape the black-and-white "wicked clown" face paint affected by ICP's Shaggy 2 Dope and Violent J. Fans collect T-shirts and hockey-style jerseys emblazoned with ICP insignia or those of other bands on ICP's recording label, Psychopathic. And the Psychopathic logo, a little red man with spiky, twisted hair and brandishing a hatchet, is everywhere in the crowd: on shirts and medallions and inked into flesh.

At an ICP show, the Faygo is the blood of the beast formed by the band and the crowd. At one show early in the group's career, a booing audience member threw some on the stage, the guys threw it back, and a movement was born. It's as much a part of the stage show as the makeup and the microphones.

Call it shtick, call it a gimmick -- many do. The group, begun in 1990, calls its violent, circus imagery the "dark carnival." The term "juggalo" comes from Violent J's early juggler persona. Six of ICP's 19 albums and EPs are known as "joker cards" and are supposed to reveal some greater truth about the world to juggalos and anyone else who listens. The final joker card, The Wraith, claims that the entire experience has been about God and righteousness all along -- the cartoonish violence was meant as retribution for the unrighteous: bigots, negative people and haters in general. From the song "Thy Unveiling":

"When we speak of Shangri-La, what you think we mean? / Truth is we follow GOD, we've always been behind him, / The Dark Carnival is GOD and may all Juggalos find him!"

Whether God is present at Club Zoo, it's still rock 'n' roll -- as in "sex, drugs and ..." One outrageously hammered fan sweats and shouts in smeared makeup: "I am a juggalo till the day I die! Everybody that is down, they care about everything. You can't feel it unless you're part of it. It's part of everything we do." The "it" is family, but it doesn't stop this fan from demanding sex acts from a reporter -- to the mortification of the fan's apologetic girlfriend.

After an opening set by Drainage X, members of that band hang outside the club, explaining their take on the dark carnival.

"It's like a fairy tale, a fantasy, a horror movie," says Spider, the bassist. His face is painted white and his eyes appear to cry tears of blood. He's done some backyard wrestling with ICP's federation, a side project of the group, and was thrilled to be invited on the tour.

"Juggalos are the most loyal fans I've ever seen," he says. As a metal band, Drainage X might not have gone over with the usual rap crowd. "If we came out trying to sound like Violent J, they'd say, 'Fuck these guys.' It's why I'm happier to go on this tour than on a metal tour."

Inside the club, the hatchet man is tattooed on the bared pecs of Doug Martin, of the North Side. "It's for life," he explains. "When they say 'family,' it's no joke. They got me through a lot of hard times, like fights with my parents. It's like therapy."

Around 9:30, after several opening bands, the crowd becomes an organism, swirling where the mosh pit will eventually materialize. A young couple squashed against the front barricade makes out frantically. Smoke of at least two varieties billows near the stage, where sound equipment is swathed in clear tarps, like the set of a snuff film in a horror movie.

On stage, two huge, hollowed-out skulls contain hundreds of two-liter bottles of diet Faygo cola -- sugary soda is too sticky to dump on eager fans, apparently. Twin crypts sit on either side of the turntable, which is behind a salad-bar sneeze guard.

Everything goes black. Blacklight strobes pulse over the crowd. With a blast of bass so loud you can feel it pushing out of the 12-foot speaker cabinets, Shaggy 2 Dope and Violent J emerge from the crypts -- shaved heads, identical black outfits and crisp, dichromatic clown makeup perfectly applied.

As the refrain "Get blood everywhere!" rises, the full-on Faygo assault begins. It never lets up, not for an instant, throughout the entire hour-long set. Violent J and Shaggy 2 Dope constantly twist the tops off the bottles as they rap and dance around, squirting them, throwing them into the crowd and shaking them up full throttle, then releasing them like hyper-carbonated rockets into the sopping crowd. Soon, ghoulish lackeys emerge from the crypts, throwing Faygo and restocking the skulls' ever-diminishing supplies. The ghouls blast Faygo from water cannons, slosh buckets of Faygo into the crowd and, between more costume changes than Britney Spears -- now they're mushroom-headed monsters, now hellish clowns -- throw feathers, confetti and streamers into the Faygo-besotted crowd.

About halfway through, Shaggy's shirt comes off and his semi-toned torso begins to steam from the Faygo, which feels freezing in the sultry club. Kids have been flinging themselves toward the stage all night, crowd-surfing on the wet, sticky hands of their family.

For the final song of the night, the orgy of thrown pop reduces visibility to blizzard levels. When the lights go on, the three-foot-wide trough between the stage and front-row crowd barrier runs thick with a muck of Faygo, feathers, confetti and several errant shoes.

Outside, the cold and stink of generic diet soda hits hard. Fans leave the show wetter than if they'd showered with all their clothes on. As they disperse into the otherwise-deserted city, a cry comes from some unseen corner: "Woo! Woo!" The reply comes from blocks away: "Woo! Woo!"

It's the family, calling to one another.

With lyrics such as "What is a juggalo? He just don't care, he might try to put a weave in his nut hair," and song titles like "I Stuck Her With My Wang" and "I Stab People," it's understandable that Insane Clown Posse could have something of a public-relations problem. And some violent criminals -- a Massachusetts teen attacking patrons of a gay bar in February, and a gang of kids in face paint mugging people in Seattle -- have ascribed their own violent impulses at least partially to the band, which doesn't help the public perception.

Any real juggalo, the band said in a statement released after the gay-bar attack, knows that the band's message, however violently packaged, is ultimately about tolerance. "Anyone that knows anything at all about juggalos knows that in no way, shape or form would we ever approve this type of bullshit behavior," said the release from band manager Alex Abbiss.

Most media accounts of the juggalo experience have focused almost exclusively on this violence, and on the outright weirdness of the fandom. But what's been overlooked, fans say, is the juggalo refuge for kids who might not have a haven and an outlet.

"It's an outlet for kids who would otherwise be getting into fights," says Anthony Walker, a 23-year-old juggalo from the city's Allentown neighborhood. Criminals invoking the band's name, "they're not down. They're just using it as an excuse," he says. "We're just a bunch of kids listening to music" -- banding together as quasi-kin.

Rick and Megan Topping, 25 and 26, live in Brentwood with a 7-year-old son and another kid on the way. "I'm the educated juggalo guy," Rick says through the makeup, touting his managerial IT job and their home and family. The 7-year-old's not allowed to listen to ICP just yet, Megan says, though he does know that Dad wears makeup to go to ICP shows. "He thinks it's odd for a boy to be wearing makeup," she allows.

"We're a big wicked clown family here," says Bryan Pitman, who traveled a long way to see the show: He's on leave from Iraq, coming today from his home in Akron, Ohio. He and his Army buddies treasure the music's ability to release their aggressions. "I'll listen to anything, whatever I can free my mind to and just relax," he adds.

Ten years ago, when Phil Mineo started coming to ICP shows, he would spend the whole time up front, enduring the violence of the pit to be close to the clowns. "It was different back then," says Mineo, 25, of Erie. "Now I'm just back here," hanging in the relatively uncrowded back of the club. He met his wife through the fandom, though she's not with him tonight -- she just had their child three weeks ago. The kid's future juggalo status is in the air, he says, since his wife is backing away from full-on juggalism herself.

Michele Knight, 21, and Paul Werme, 25, say they've been to scores of shows -- almost 50 between them. They've been fans since about a decade ago, when they used to paint up.

"I like [the music] because of the issues they bring up -- 'Hell's Pit,' 'Crooked Preacher Killa,' those are about the priests and what they did to the kids and how it was wrong," Knight says, echoing the notion that all the dreadful violence is meant to be retributive.

"People who don't listen just think we're freaks."

At 25, Michael Sorg is Pittsburgh's juggalo elder statesman.

He's a husband, homeowner and film editor by day, but his spare time is dedicated to maintaining westernpajuggalos.com, and making music of his own in an ICP tribute group called Crap. The Web site includes wife Melissa's juggalo advice podcast, the Missfit Advice Hour. She also answers questions on the site -- questions like: "I am a juggalo and have been for quite some time, but I also like other rap music like Juvenile and like Jay-Z. Does this mean I'm not a true juggalo?"

"Down is down!" she replied. "As long as you're down, that's all that matters. Being down isn't just about the music. It's about the sense of belonging and the sense of family. As long as you're down with that, that's what makes you a juggalo."

"It's partly proximity" to Detroit, says Michael, that's made Western Pennsylvania such a juggalo hot spot. "People have told me this was one of the original clown towns." Some ur-juggalos scoff at newbies, whom Sorg calls mall-a-los for picking up their merch at Hot Topic or Spencer Gifts instead of at shows.

There are gradations in the fandom too, he says. "A lot of people need to prove how down they are."

He's moved past that now, he adds: "I haven't done the face paint since 2001." That was for the Gathering of the Juggalos -- a mobile yearly outdoor festival that draws thousands of juggalos and bands from Psychopathic's roster. "We slept in the car for three days," he recalls. After that, "I didn't want to touch face paint."

One local fan's tattoo commemorates the beef between ICP and another white rapper from Detroit, Eminem. A mountain of skulls climbs the guy's shoulder, and the top of the pile is crowned with a pike impaled with the pretty blond head of Marshall Mathers, bleeding from the mouth. The bad blood started when Eminem circulated a flier for a show of his saying that ICP might stop by, without having cleared it with them first. The two camps have traded barbs in dis tracks ever since, notably in ICP's "Nothin' But a Bitch Thang."

Days after the Club Zoo show, another show celebrating the five-year anniversary of Sorg's Web site was held at HKAN, a South Side hookah bar. Featuring Crap and other local ICP-flavored groups Twisted Thoughts, Broken Wingz and No Clue, it was part of the club's weekly "Hip Hop and Hookah" series. Emcee Ryan Cassidy of Basick Sickness, an up-and-coming local hip-hop act, hosts the show and did a set. While his tastes run far and wide, Cassidy, 23, is unable to disavow his juggalo roots.

"Back in the day, I was diehard," he says. "I had enough [ICP] shirts to wear every day for a month." His horizons have widened, but he still goes to the shows, and at Club Zoo, was in the pit in front of ICP. "Once you're a juggalo, you can't shake it." He recalls his mother picking him up after shows back in the day, "Her car seats were covered in garbage bags" to keep the Faygo off, he says. "She made me strip down to my underwear!"

It's easy to misunderstand what ICP and juggalos are all about, he says: "When it comes to artists, [ICP] doesn't get one ounce of respect: It's a gimmick, a bunch of white dudes in face paint throwing Faygo around, are you kidding me?"

But even the band's business acumen commands his respect. "Those motherfuckers are hustlers," he says. "They're eatin' off the music and they aren't on MTV dancing around in shiny jumpsuits. Granted, they're in clown makeup, but no label told them to do that. They've never had a major label backing them."

"Never" is not exactly accurate. The fourth joker album, The Great Milenko, was initially released by Disney-owned Hollywood Records. After Disney board members objected to some of the content, the group excised three tracks from the disc. But hours after its release, the album was pulled from shelves and ICP was dropped from the label.

The record was later re-released in its original form by Island Records. The publicity helped make it one of ICP's most popular albums, leapfrogging to platinum status from the controversy.

What most people outside the fandom don't understand, says Michael Sorg, is the idea of God hidden in the violence of the lyrics.

"They're not by the letter," he says, "but it's in there."

Josh Trafinchick's induction into the family happened at age 6, when he found an unlabeled cassette tape he only later identified. But his fixation has only grown. Ten years later, the baby-faced high school student bears tell-tale signs of his fidelity -- piercings and tattoos, ritual garb and an obsessive collection of paraphernalia, both purchased and homemade.

A moment in his presence, in his Belle Vernon house or walking down the street, betrays his ICP allegiance. Other disciples recognize and greet him. He spends hours each day before his computer, maintaining his Web site and communicating with other juggalos across the country. His mother, Wendy Fitman, at first skeptical of his devotion, soon found herself something of a devotee. She started istening to the music she'd only tolerated before, even when Josh wasn't around.

"It's truthful," Wendy says. "It's stuff you want to say but don't." Wendy wouldn't go so far as to classify herself as a juggalette, but she's wearing a T-shirt of Twiztid, a Psychopathic band.

Sitting in the kitchen of their neat, cheerfully decorated home -- country-style Americana, Halloween and, in Josh's bedroom, wall-to-wall ICP -- the pair share an easy affection. Josh is as tolerant and respectful of his mother as any 16-year-old could be expected to be. They both talk about Josh going to college, since he is putting in all those hours teaching himself programming languages to run gzninjas.net. It's already the top-rated site on top100psychosites.com, a site that ranks juggalo sites by counting how many visitors each gets.

Josh played the foundling cassette tape and liked the sound. It spoke to him -- and it was lots of fun. As he got a little older, he searched out the lyrics online and realized this was The Riddle Box, ICP's third joker card. He read up on the group and started downloading its music. By the time he was 14, in addition to the hatchet man on his shoulder, he had juggalo spilling down his calf.

When Wendy and Josh had lived previously in Johnstown and she started a new job, one of her coworkers began gossiping to her about a strange new kid at their children's school -- a kid with blue hair, piercings and tattoos. "I said, That's my son," Wendy recalls. "I explained that I'd rather him do this, that's not hurting anyone, rather than the drugs and the alcohol. I get a lot of flak from it but I stick up for him."

Wendy says such criticism, which she hears from other mothers, was not entirely unexpected. She was so worried about getting into trouble for allowing Josh to get inked at 13 that she checked first with the county's child and youth services office. But she's proud of her son, his self-taught programming expertise, his avoidance of drugs and booze, and his creativity.

Josh and Wendy say that miscreants in face paint who commit crimes such as the Massachusetts gay-bar attack, or Seattle park muggings, aren't really juggalos, and that the music couldn't motivate criminal behavior.

"That's bull," Josh says. "Just because someone's out there doing something retarded and saying, 'I'm a juggalo' ... they're not a juggalo. If you're a juggalo, you just kick back, you like the music. We don't want fights. We don't want all the drama."