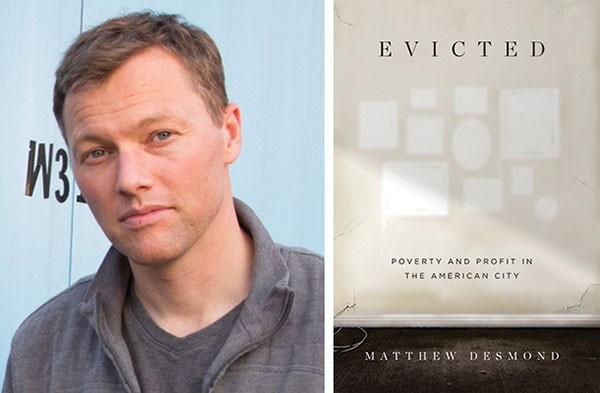

Harvard sociologist Matthew Desmond’s new book Evicted reads like a novel, but tells the true and heartbreaking stories of tenants and landlords dealing with eviction and its effects on their lives.

He’ll discuss the book at a lecture at Carnegie Music Hall on Thu., Aug. 4, hosted by Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures. Evicted (Crown) is set in a poor section of Milwaukee in 2008 and 2009, and includes a cast of characters struggling to survive that includes women with children, an amputee in a wheelchair, and a nurse-turned-heroin addict, as well as a landlord and a trailer-park owner who alternate between trying to help their destitute tenants and working to stay afloat themselves.

“I had no idea when I started [the book] that eviction was such a common, critical experience,” Desmond says in a phone interview, “and no idea how directly it was contributing to poverty.”

Desmond says that part of the book’s mission is to acquaint readers with the texture of poverty. “We sometimes talk about poverty in America in a really simple way,” he says. “But poverty is complicated.”

Eviction, Desmond found, is more often a cause of poverty than it is a condition of being poor, and once it starts, the cycle of living in substandard, unaffordable housing is extremely difficult to break.

Many of the situations Desmond writes about in Milwaukee apply in a lot of American cities, he adds.

“The story of the American city is often written at the margins; we have a lot of books about New York and Los Angeles and Detroit. But writing a book about Milwaukee, or Indianapolis or Cleveland or Pittsburgh, you have a shot at representing the broader experiences of housing insecurity being felt all over the country.”

He notes that within the Rust Belt, most poor renting families spend half of their incomes or more on housing. Many families who qualify for housing assistance must wait years, in some cities decades, before they can get placed because the wait lists are just too long.

Here in the Pittsburgh area, roughly 30 percent of the population lives below 200 percent of the federal poverty level of $24,250 for a family of four, according to the Pittsburgh Foundation. The organization is sponsoring Desmond’s visit to Pittsburgh.

“While our city is certainly on the rise, nearly one-third of the people who live and work here cannot get access to the improved economic and cultural life of Pittsburgh,” says Maxwell King, president and CEO of The Pittsburgh Foundation.

And cities can have that economic prosperity and success and still address affordable housing, Desmond says: “They don’t have to choose.” He points to Boston, Seattle and New York as examples of cities working toward solutions, and organizations like Right to the City, for raising awareness of America’s affordable-housing crisis.

One of the more high-profile evictions in Pittsburgh is still playing out. Last summer, LG Realty Advisors issued 90-day eviction notices to residents of the Penn Plaza apartment complex, one of the few remaining below-market housing options in the neighborhood. City officials arranged agreements between LG and the tenants to provide relocation help, delayed move-out dates and other assistance, and a fund was created to pay for other affordable-housing projects in the future.

As of this writing, one of the buildings is half-demolished, and residents in the other building have until March to find alternate housing. About 60 tenants remain.

Last week, Whole Foods announced it had signed a lease to build a 50,000-square-foot store on the site of the mixed-use East Liberty Marketplace complex that will replace the apartment buildings.

But Sherman says the general pattern for evictions nationally doesn’t show all of them happening in gentrified neighborhoods.

“They tend to happen in poor neighborhoods, where there isn’t a Whole Foods, or a juice bar,” he says. These are neighborhoods where the cycle of poverty is nonstop, whose residents are largely forgotten, he adds, and who have little influence or voice.

In Evicted, Desmond advocates for a universal housing-voucher program, which would cover all families under a given income level. He says vouchers are a more feasible and cost-effective option than developer incentives to build affordable housing, or new construction.

Since doing the research for Evicted, Desmond says little has been done to change the plight of poor people on the verge of homelessness.

And for those living in poor neighborhoods where eviction rates are highest, the cost of eviction is community, he says; there’s no stability, and no trust among neighbors who move in and out every few months. That translates into very little political capital or ability to effect change from within.

“It’s important for these neighborhoods to become communities instead of places people churn in and out of,” he says.