Pittsburgh has the most extensive busway system in the entire country. There are about 19 miles of grade-separated, traffic-free busways that spread across three lines throughout Allegheny County. The East Busway, which runs from Downtown to Swissvale, is one of the most efficient non-heavy rail transit corridors in America. When compared to other transit lines in mid-sized Rust Belt cities, the East Busway is arguably the best, carrying around 24,000 riders a day.

But Pittsburghers generally don’t see busways as a unique asset. In fact, many people don’t even know they exist. Most stations are cast-off under bridges or surrounded by blight. Unlike transit stations in cities like Boston or Berlin, most of Pittsburgh’s busway stops lack retail and housing development nearby. The busway lines, East, South, and West, aren’t always seen as worth expanding.

When transit proposals are discussed in Pittsburgh, the ideas usually sought after are a light-rail to the airport, building new highways, or even more ludicrous ideas like the hyperloop or ziplines.

Local advocates, urban-policy specialists, and public-transit experts are trying to change that. They laud the busways for their importance to the region’s transit, but they see a unique opportunity in Pittsburgh to expand them, increase their marketing, and redevelop the land surrounding their stations. Those changes could reduce traffic, lower greenhouse-gas emissions, decrease cost-of-living expenses for thousands of residents, revitalize neighborhoods, and combat income inequality.

It may sound too good to be true, but increasing affordable and convenient access to the more than 150,000 jobs in Downtown Pittsburgh, not to mention the thousands more that could be created along the busway with redevelopment near several stations, could be game-changing in terms of fighting poverty.

Christof Spieler is a transit expert who wrote an atlas of America’s public transit systems called Trains, Buses, People. He visited Pittsburgh last year during the Rail~Volution transit conference, and was amazed at the efficiency and practicality of Pittsburgh’s busways, but believes they can be vastly improved.

“[The busways] have amazing potential and I feel like Pittsburgh isn't doing enough to maximize that,” says Speiler. “They are marketing to the public like they are just regular buses, when they are not.”

Proposals exist and advocacy is growing, but backers say making improvements will come down to whether Pittsburgh leaders apply the political will and the desire to boost the busways. Will everyone get on board?

At the time of their construction in 1977, Pittsburgh’s busways were revolutionary. Utilizing existing right-of-ways from trolley lines and the Pittsburgh Railways Company, the guideways operated like light- or heavy-rail train lines, but with buses instead of rail cars.

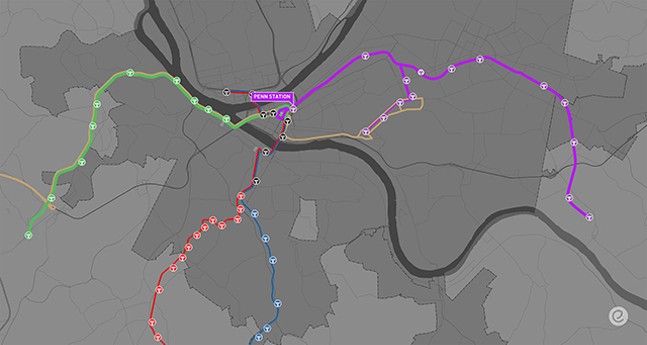

The South Busway, which runs alongside the Blue light-rail line from Beltzhoover to Overbrook, was completed first. The East Busway, later renamed the Martin Luther King Jr. East Busway, was completed in 1983 to Wilkinsburg and later extended to Swissvale in 2003. Before the East Busway was completed, travel times from Wilkinsburg to Downtown were about 45 minutes; now it takes about 15 minutes on the busway. In 2000, the West Busway opened and now transports passengers from Carnegie to Elliot in the West End. They are all owned and operated by the Port Authority of Allegheny County.

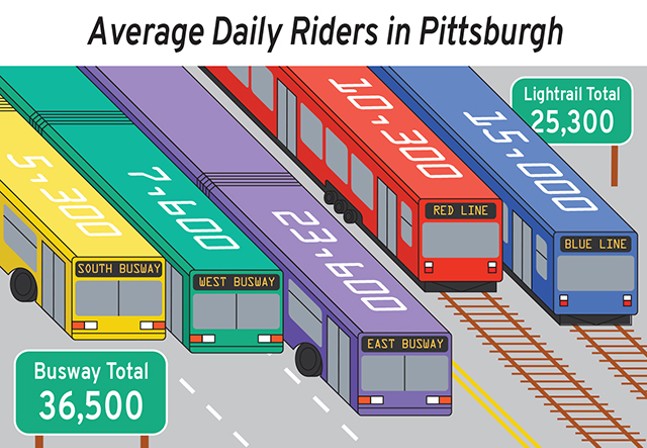

According to the most recent Port Authority figures, average weekday ridership on the busways is about 35,500, which is about 15 percent of weekday ridership. The East Busway alone carries just a bit fewer passengers everyday than both the Red and Blue light-rail lines combined. According to Pittsburgh’s bid for Amazon HQ2, the busways could immediately accommodate up to 60 buses per hour and expand by 200 percent without major capital investments.

“The idea that the busway is an inferior thing and that rail is the superior thing, I would disagree with that,” says Spieler.

One of the advantages of busways is buses can exit the guideway and ride on regular city streets. Spieler says this allows them to service low-density suburbs and bring in more riders to the busway, where commutes are quick. And since Pittsburgh has experienced and continues to experience suburban sprawl, busways are likely the best way to service the region, says Spieler. Busways also allow for emergency vehicles to skip traffic, something light-rail can’t offer.

It’s why the East Busway, which is about nine miles long, can have the high ridership of about 23,600 people a day. For comparison, a nine-mile light rail line in Charlotte only brings in about 16,500 riders a day.

Spieler says the simplest way to raise the profile of Pittsburgh’s busways, and potentially increase their already robust ridership figures, is to market them as they were originally intended. He says the Port Authority should rename the East Busway the Purple Line, the South Busway the Yellow Line, and the West Busway the Green Line, and have buses that ride on each busway match those corresponding colors. The reason each busway route starts with P, G, or Y is because each busway was originally assigned the color purple, green or yellow.

Spieler says this would indicate busway buses are different than those on other lines. A busway bus only takes 11 minutes to get from Downtown to East Liberty while a car in no traffic takes 15 minutes. Even without branding and other improvements, Pittsburgh’s busways still outperform other BRT-like systems in the country. Per guideway mile — areas where the buses are completely free of other traffic — Los Angeles busways carry about 877 passengers daily, while Pittsburgh carries about 1,921 passengers.

Port Authority spokesperson Adam Brandolph says the agency is supportive of a rebranding effort for the busways.

“We are interested in and have already had several discussions about branding our fixed guideways,” says Brandolph.

Once a rebrand is complete, Spieler suggests making stations more accessible to pedestrians and people with disabilities. Many stations typically have access only on one side of the busway.

Increased access to busway stations should be a development priority too, says Chris Sandvig of the Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group (PCRG). He says more stations should be surrounded by dense mixed-use development that combines housing, retail, office space, and amenities; what he calls “transit orientated communities.”

“We still have this hangover of a hangover that any development is good development,” says Sandvig about Pittsburgh. “We have extreme transit dependence along the East Busway. We need to stop building in places where there aren’t people.”

PCRG studied all the areas within half a mile of all busway stations. If this was considered a neighborhood, the population would be 115,000, with an average of about 10,000 people living near each station. Residents in this “neighborhood” average 1.33 public transit trips for every car trip. More than 76 percent of residents near busway stations own between zero and one cars, meaning they require less parking and car infrastructure that can be costly to developers and cities.

Sandvig says these areas should be attracting development, and if zoning changes were made to lower or eliminate parking minimums, that development could become affordable for low-income residents and tenants. And opportunity exists: about 18 percent of the land surrounding stations is currently vacant.

“You could live all your life and not have to leave the busway corridor,” says Sandvig, noting the job centers emerging in places close to the busway in the Strip District and East Liberty. He adds that encouraging people to live car-free would help reduce congestion and greenhouse gas emissions, too.

Sandvig says land near the Herron and Wilkinsburg stations would be ideal for dense, mix-use development. Currently, there are 17 acres of lightly used land surrounding the Herron busway station. According to a 2017 Urban Land Institute study, the Herron stop could accommodate more riders and building transit-oriented development (TOD) there “offers many transportation advantages to the city and region.”

Wilkinsburg has already proposed TOD near its station, which is currently surrounded by more than 600 parking spaces in a surface parking lot.

Brandolph says the agency does have TOD guidelines that “call for dense, mixed-use, walkable, and, when possible, affordable development connected to high-quality transit service.” Port Authority also owns land near the Negley Station in Shadyside and has a detailed plan for TOD and increased pedestrian access.

“[The busways] have amazing potential, and I feel like Pittsburgh isn't doing enough to maximize that.”

tweet this

But for all other busway stations, those guidelines are merely suggestions and many municipalities throughout the region haven’t implemented TOD strategies into their rules.

The right kind of development near the busway isn’t just a strategy to fight blight, it can help fight poverty too. A recent study from Cleveland State University found that Cleveland neighborhoods that gained access to transit saw poverty rates fall by about 13 percent after 10 years, and overall employment in those areas increased by 3.5 percent.

“To be so close to the busway to help them earn income, that’s nothing to sneeze at because a lot of opportunities to earn income, you have to have a car,” said Nisha Blackwell, founder of Knotzland Bowtie Company. “It really knocks down some of the barriers people face.”

Laura Wiens of Pittsburghers for Public Transit agrees.

“The people who can’t afford cars, are being forced out into the peripheries,” says Wiens. “What we see in this county is areas where transit costs exceed the cost of housing.”

McKeesport has seen a large influx of low-income residents over the years, and according to Chicago’s Center for Neighborhood Technology, McKeesport residents spend 21 percent of their incomes on transit, and only 16 percent on housing.

“If it takes 90 minutes on the 61C bus to commute from McKeesport, then you are not going to get out of poverty,” says Wiens.

Sandvig says Monroeville is also a good candidate for a busway extension, which could have the added bonus of reducing traffic congestion on I-376, since residents could take the busway instead of driving Downtown.

Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald says he supports extending the East Busway through Braddock and would eventually like to see the West Busway extended to the airport. He says developing densely around transit stops, busway and light-rail, should help improve air quality by reducing driving.

“We just can’t grow with the amount of cars that want to drive on the parkway. I really want developers to use these areas,” says Fitzgerald of busway stations. “That is a big part of my economic development strategy.”

Fitzgerald says he has showcased sites near busways to developers and notes that redevelopment at the Lexington Technology Park near the Homewood Busway station includes housing and offices.

“We do really want to continue to grow around the busways,” says Fitzgerald.

State Rep. Austin Davis (D-McKeesport) was recently placed on Port Authority’s board, and has the backing of PPT, since he supports extending the busway. State Rep. Summer Lee (D-Swissvale) tweeted in February about how important the busway is for economic development, especially in Mon Valley communities.

“We can't truly have economic development in the Mon Valley without increased affordability and accessibility to public transportation,” Lee tweeted. “We need the busway extended throughout the Mon.”

And with state and federal public transit funding likely to be reworked before 2022, thanks to the expiration of the funding stream from the Turnpike Commission, Sandvig says creating a transit vision centered on the busways is timelier than ever.

“We have to get behind that vision and sell it to Harrisburg, Washington, riders, and our neighbors,” says Sandvig. “Now is the time for it.”