In the introduction to Hidden America, Jeanne Marie Laskas suggests that this collection of her reportage about underappreciated jobs is slightly subversive. After all, "our celebrity-driven culture," she writes, is about being seen, being feted and getting rich quick. It barely deigns to acknowledge folks grinding it out like the truck drivers, coal miners and landfill workers whom her book depicts and honors. Yet these are "the unseen people who make this country work," she writes: "the people who .... [w]ere they to walk off the job tomorrow, would bring life as we know it to a halt."

And Hidden America is good stuff. Sometimes it's even great stuff — even as Laskas' own insistence that her book is apolitical feels, if not disingenous, at least at odds with its very content.

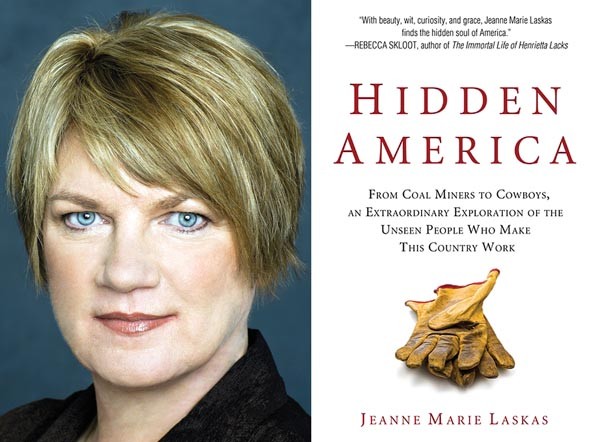

Laskas is director of the University of Pittsburgh's writing program and a top writer for national publications. In fact, versions of six of her book's nine chapters previously appeared in GQ, and a seventh in Smithsonian.

Her style is crisp, deceptively light, with an eye for detail and an ear for humor. Here's how she opens "Underworld," about coal miners in Cadiz, Ohio (an hour west of Pittsburgh):

He handed me a salt-and-vinegar potato chip. We were more than five hundred feet underground, sitting on a blanket of powdered limestone, up in section two and half south. I asked him if there was anything he enjoyed about coal mining.

He thought a moment. "I'm gonna say no," he said.

Laskas is usually a character in these pieces, befriending and cajoling her subjects even as she interviews and observes. And she finely renders the microcosms populated by Texas cowboys, Arizona gun salesmen, migrant Latino blueberry-pickers in Maine and air-traffic controllers at LaGuardia. The coal miners are gruffly kind, brutally funny and very talkative, the cowboys charming, even as their trade now includes hormone injections and artificial insemination (manual). The air-traffic controllers are a bitter lot — angry at both the feds and their union, overworked and certain that some catastrophic human error is inevitable.

Laskas' prose can be lyrical, too, as when she depicts the migrants raking blueberries to a radio soundtrack: "The sugary blueberry smell came out with a rhythmic punch as the brush was continually jostled, and the shush, shush, shush of the rakes was roughly in time with the thumping beat coming from the trucks."

Hidden America offers plenty of easily digestible technical details about these jobs. But what drives the book is Laskas' genuine interest in who these workers are, not just what they do. That's especially plain in arguably the book's best chapter, "The Rig," about oil-rig workers on Alaska's North Slope. In this supremely remote, alien habitat — punishing cold, constant dark — Laskas beautifully depicts these men, many of whom are psychologically damaged, and a few of whom seem certifiably nuts.

Like many of the folks in Hidden America, lots of oil-rig workers seek employment that allows them to escape from the stresses of everyday life. (They're "hidden" partly because they're hiding.) But Laskas' empathy for these guys seems special, as when she sums up after describing an horrific accident: "Roughnecks live terrible shit like that, the kind of constant shit that can bond a man to another for life, like combat soldiers who easily shrug off each other's madness." "The Rig" also features a virtuoso, novelistic passage about drilling a difficult well, and even a shock ending.

Hidden America has imperfections. The otherwise engaging chapter on Cincinnati Bengals cheerleaders, for instance, feels thematically astray: Would "life as we know it" really "halt" without pro football's sideline dancers?

But the book's main flaw, curiously, is that Laskas frames it as resolutely apolitical. "My own political views have no place in this book," she writes in the intro.

True, writing about the faceless rather than famous might not be a partisan choice. But it is political: a paradigm shift, as Laskas herself writes. How is it not political to put faces to political straw-men like immigrant workers and gun salesmen? In a funny and thoughtful chapter on the engineers and heavy-equipment guys who staff a Southern California landfill, Laskas insists that we should know what it takes to dispose of our oceans of trash. Knowledge begets responsibility, which is where politics begins.

Likewise, leaving things out can be a political choice, too: In writing about the people who extract our two dirtiest fuels, for instance, Laskas barely mentions environmental issues. What do these coal miners think about global warming, which is changing the very face of the planet?

Still, Hidden America is a fine book — even if Laskas feels compelled, for some reason, to deny some of its most basic impact.