How did Ed Piskor go from drawing comics in his parents' Munhall basement to standing alongside the likes of R. Crumb as an illustrator for comics icon Harvey Pekar? By being fast, cheap and good (not necessarily in that order).

In 2004, Piskor met a short deadline for a long story in Pekar's book Our Movie Year, written in the wake of American Splendor, the acclaimed biopic based on the lifelong Clevelander's long-running comics series. The following year, Pekar asked Piskor to illustrate a new graphic novel. Macedonia, adapted from original text by graduate student Heather Roberson, recounts her trip to the Balkans to learn how war was avoided in the 1990s in that one small country in a war-torn region. It's due May 1 from Villard Books.

Piskor, 24, still lives at his folks' house (with his three younger siblings) and draws in his basement studio -- a glorified cupboard lined with cartons of comic books and shelves of bound volumes, from The Essential Fantastic Four to The Complete Crumb Comics. Wearing a Leatherface T-shirt and camo pants, his wrists adorned with matching studded bracelets and a digital watch, Piskor spoke recently about Macedonia, the art of comics, and working for Pekar.

How did you feel about drawing Macedonia?

It seemed daunting. I've never been out of the East Coast here, man. I have no idea what goes on in Macedonia. I don't know which side of the road these people drive on.

Pekar recruited you in April 2005.

I didn't have much time to think about working on this thing. It was just working on pure adrenaline. If you take a look here, this is the artwork for this book. It's like this high [spreads his hands 2 feet apart]. I just plugged through. I worked on it seven days a week for 14 months straight. I pulled like 30 all-nighters -- just because I was real excited about it. I would lay down and I just couldn't sleep. I would blink and it would be 9 o'clock the next night. It felt like cartoonist boot camp.

What excited you so much?

I always wanted to draw comics, man! I'm just imagining the final product. I'm drawing comics for cash. I'm sitting here in my boxer shorts. My friends have to wear collared shirts, with ties, they gotta get up at 9 a.m., they take lunch at 12:15 or something. I could get up, make my own hours. It felt pretty cool.

Does Pekar send a lot of instructions with his scripts?

On the other stuff I did [Our Movie Year], I had to pencil these comics, and I had to send them to him; he would look them over. It was actually good that he did, because the way that I drew his wife in those strips? Awful. That's all I'll say about that, man.

But with [Macedonia], he was confident enough in me to just let me go nuts, and it kinda required a lot of tweaking of his script anyhow.

Because there's so much text?

A lot of his stuff, it would amount to small heads at the bottom of the panel, with this avalanche of dialogue. It required that a lot of that stuff get broken up. That's why there's sometimes like 12 drawings on a page, when initially he wanted four.

How much liberty did you really have?

Every piece of text needed to remain. But I added a lot of stuff, because his scripts, it's just two little stick figures with dialogue.

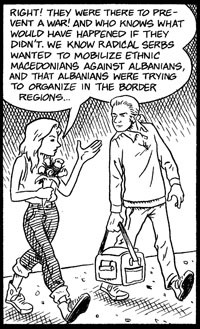

Early on here, [the Roberson character] meets her boyfriend. This is a 12-page conversation, and the way it read in the script is just these two heads, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. So I have her meet him at the train station. They get in the car, they're driving home. They reach home, they set their things down, they start making dinner, they water the garden. You kinda have to do that to just make it interesting. The reader I don't think would put up with two heads back and forth with all this like florid prose.

So you just made all that up.

Yeah. I think if he would have laid that stuff out, it would have probably saved us two months of time, of me just wasting mental energy trying to think of where the heck should I put these talking heads.

Why these particular actions for this sequence?

I wanted to give the impression that a lot of time was going by. The way it was initially written, that could have been a simple 15-minute situation.

Did you intend the pictures to comment on the words?

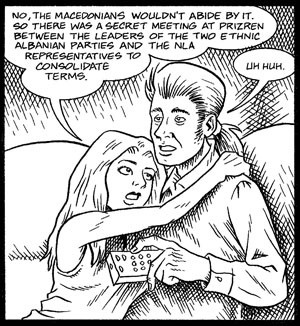

There were certain things. She gets sort of on a soapbox. I made sure to make [the boyfriend's] panels very constrained -- he only gets this much time, while she gets all of this. Some of the subtext that I injected, she's kinda going off, where he's getting maybe one, two words in edgewise. He has the television controller, and his eyes are getting tired. And she's hugging him, and she's still going on and on and on and on.

When I sent these pages to her, she was like, "You captured this exactly right!" She explained that she would hug him, and it was supposed to be a tender moment, but then she would get back on her soapbox and just get so excited about the whole idea, about Macedonia and the Albanian minority and all this stuff, and it really put a strain on their relationship.

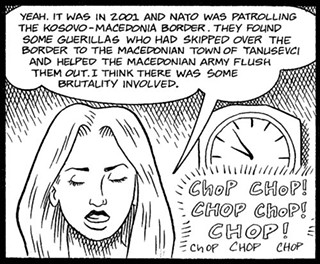

Here Heather's chopping vegetables while talking about warfare. Were you intentionally being ironic?

Man, we'll call that a happy accident. It was a pure adrenaline rush, this whole thing. A lot of interesting stuff happened, but it was only upon looking at it afterwards that I found it interesting.

What did you base the characters' appearances on?

She sent me like one photograph of the [boyfriend]. Most of the other people were just made up. I always like to inject my dad into the comics: He took the role of this crazy taxicab driver guy who was trying to hustle these broads out of their cash. That's when he had teeth. He doesn't have them any more.

I liked the Yugoslavian guy on the plane.

With the like 1980s LL Cool J outfit.

The funky hat and the Adidas sweats.

I just always like on TV when they show people in a club scene and they talk to Russian people, they always wear what we wore back in '87.

The story overall has little high drama.

It's a Harvey Pekar story, and there's not usually big guns or knock-out fights. I expected it to be a very conversational thing, and the dialogue between the characters would move the story along. The money shots that I wanted to get in there were just like interesting backgrounds -- cool drawings that were kind of big -- whenever I had the opportunity.

It's also a complex book that asks a good bit of the reader.

Stupid people don't read these kind of books anyhow. ... This story was kinda serious as a heart attack. Harvey's known for his slice-of-life stuff, and life is a series of conversations.

When characters tell stories, why not illustrate what they're telling?

I think it would take away from the conversation. I've been getting really, really fascinated with the passage of time between panel and panel. I thought it was cool to draw a character holding a coffee cup and then bringing it to its face -- it's the closest thing to animation that I'll ever get to.

It might not be as cool as going back in time and showing bloody heads or people getting beat up. But there's a school of thought that if they're talking about it, then you don't need to show that. We don't need to beat the reader's head with [it].

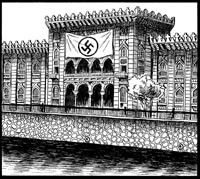

In this section on the history of Yugoslavia, which formerly included Macedonia, you do more illustrating.

It was probably the most complex thing. It was just all this text, and there was nothing to go by. [Pekar] had no idea for the images. It might have just been her head, talking to the reader, and I didn't think that would fly.

I spoke with Heather, and she wanted maps for almost all of this stuff. Maps don't work good in comics. [Readers] need to see something really visual, and a map just doesn't cut it. That's too National Geographic. So we came to a compromise. We have a couple maps and I researched it a little bit and I came up with some scenes. Google Images helped us out a lot. She would talk about specific buildings. It was this particular hotel -- you would type it into Google Images and the exact building would come up!

Had you ever drawn from a female point of view?

Never have.

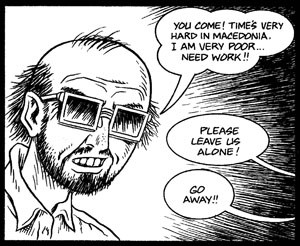

There's this motif of Heather's run-ins with men ...

Misogynists. That was definitely a running theme, of guys trying to take advantage of her.

She asked me if when this book comes out if I would go there. I told her I had the utmost respect for her, because I think I would be completely taken advantage of.

Looks like you had fun drawing these menacing guys, though.

I just like to draw ugly people.

Joe Sacco, who's drawn for Pekar extensively, did his own book about visiting the contemporary Balkans, Safe Area Gorazde. Did you read it?

I kinda wanted to, but I knew that would be a tremendous mistake. I would start working on this thing with all that stuff on my mind. We're going to be compared to Sacco when this thing comes out anyhow. That's a losing battle. We have to try to figure out how to sell this thing as a Harvey Pekar story.

Discussing your craft, you've noted how you've progressed in just a few years.

Starting out, whenever you start to develop a marginal amount of skill at this stuff, I think there's a ridiculous kind of overcompensation, a small-dick complex that a guy gets. You use a lot of detail because you have no confidence. You're hiding a lot of mistakes. You want people to get hypnotized by all this line work or something, because you don't want them to see that maybe you can't draw eyes perfectly symmetrical.

It takes confidence to do something simple?

I think all cartoonists eventually move toward a pretty simple style, where every line is in service of the story. The little cross-hatching details don't matter. You should have confidence in your foundation kinda linework. There's a school of thought where if your eye lingers on a panel for too long -- where if you're like, "OK, this is a '78 Camaro dashboard, and they have an Alpine tape deck" -- that takes away, and you're lingering too much. It should be boom boom boom boom boom.

Who are your formative influences?

I would say Robert Crumb is my top. Whenever I worked on that Our Movie Year book, he had a couple pages in there, and this is the accomplishment of like three life goals for me. One is to get paid drawing comics. One was to work with Pekar on a comic. And the other was to appear on the same place as Robert Crumb -- my God! I looked up to this guy my whole life practically. I was 13, 14 years old, I had to get my parents to take me to Phantom of the Attic to get me these disgusting, pornographic comics. I had to convince them that it wasn't for the nudity or the perverted situations. This guy drew beautifully.

Why do you jibe with Pekar?

He understands that I'm really into the history of this medium. I have a real fondness for the underground artists of the '60s. We can just talk about this stuff endlessly. ... I think he likes the idea that he's giving this kid his start. He gave me this chance, and I started getting better and better.

Are you planning more work with Pekar?

We are working on a book about the Beat Generation. This is one of the best things I ever read from Harvey. I can't wait to draw this thing. ... The editors are getting every piece of dialogue perfect, because they know I letter this stuff by hand, and a lot of people do this stuff by computer, and it's easier that way because you can just retype something. But I like the human feel of just hand-lettering.

What about doing some more of Pekar's autobiographical stuff?

I am itching to get back to just drawing him in a comic. He appreciates me drawing him with liver spots, and veins and stuff like that. And it's funny to draw your boss as ugly as you want to.

Are you working on your own stuff, too?

One of the reasons why I do this stuff is to make money to sit around and do comics on my own. My idea is to make a name for myself with this stuff [like Macedonia]. I think I heard Martin Scorsese say it: "I'll make one for the studio and I'll make one for myself." That seems like an excellent recipe for creativity.

Who are you reading lately?

There's a lot of people who produce mini-comics. They put them together on Xerox machines. You go to Office Depot and hook this up. They're starting to break out. These publishers are becoming aware of them. There's not so much money to go around where these people could quit their day jobs. But they're able to not have to think about distributing and printing, and they can just focus on the comics.

There's this guy named Dan Zettwoch who's doing a fantastic comic. Kevin Huizenga does a comic called Or Else. Robert Crumb's daughter, Sophie, and I, we edited a few mini-comics anthologies.

Any newspaper strips you like?

Nothing now. But there's been so much great reprinted material coming out, there's not enough hours in the day to read it all. They're reprinting these Popeye strips from like 1928 to 1938. Fantastic. They're reprinting the run of Chester Gould's "Dick Tracy."

As a fan-boy, that's one my favorite interests. I don't really read that so much for inspiration, as much as it's just really fun to me. "Gasoline Alley" reprints. A lot of stuff from when comics was a very new art form, and there were almost no rules. These people were really making stuff up as they went along. They [did] a lot of stuff that worked really well, and hasn't been done over the past 50 years, say. That kind of stuff can be used and retooled for modern comics, and people would see you as being a very clever guy even though you're stealing from somebody who did something in 1925.

So you're a full-time artist now?

Yeah! It's really cool. I live here with my parents, but I could easily live on my own. This book would have taken 16 months if I had to worry about making dinner and things like that.

At my girlfriend's place, she got me a drafting board, so I'm gonna work there too, man! I have a couple places I can post stuff and draw comics.

It sounds like a lot of hours.

I'm parlaying it into a decent living. Slightly over poverty wages, probably. You don't calculate hours if you're doing something you love.

You can't see too many punk-rock shows when you're drawing comics. I like to go out with my friends and wreak havoc, but I think they understand that it's just not so much a possibility nowadays.