For more than 100 years, the one constant in Pittsburgh's transit history has been the desire to give public transportation the right of way ... and the inability to do it comprehensively.

A 1906 study proposed "a system of underground railways" including "a downtown loop with a radial line to the east and several intermediate stub lines extending north and across the Allegheny River."

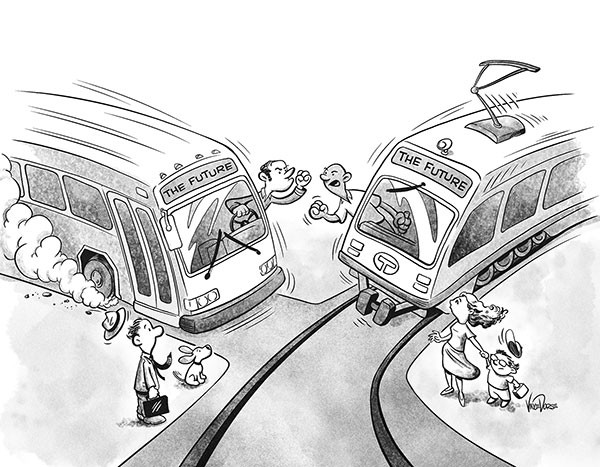

But where rail was once seen as the way to address the competing claims buses and cars have on street traffic, Bus Rapid Transit (or BRT) is gaining momentum.

The idea behind BRT takes the philosophy of rail and applies it to the bus: fewer stops, off-board fare collection, screens that show how far away the next bus is, and separate traffic lanes with signals that give buses priority.

And the Port Authority — which was among the first to borrow some of these rail-like characteristics on the East Busway — is looking to create a BRT system in the Oakland-Downtown corridor, at an estimated cost of $200 million.

"The goal has always been to link Oakland and downtown Pittsburgh, the two largest job centers in the region," says Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald, an ardent supporter of BRT. The current system, he says, doesn't make people want to forgo driving.

But some worry a BRT system between Oakland and Downtown goes too far, by spending scarce capital on one of the region's most heavily served transit corridors.

"That's a lot of money to invest in that corridor for the benefits that would result," says Helen Gerhardt, a transit activist who writes for a blog called Buses Are Bridges. "We have so many communities that only have one bus per hour."

Others worry planning hasn't gone far enough, that the focus on BRT is closing off more thorough discussions about whether other corridors deserve upgrades, and whether rail should be in the mix.

The plan the Port Authority outlined last November would require converting an existing lane of either Forbes or Fifth Avenues to be "bus-only," so both inbound and outbound BRT routes would have their own right of way. (Currently, only outbound routes have their own lane through Oakland on Fifth Avenue.)

That would render the several 61 and 71 buses, which currently run through Oakland along Fifth and Forbes avenues, unnecessary in a corridor that serves about 30 percent of the region's transit ridership, Fitzgerald says. Instead, BRT could replace buses that often stack up behind each other.

BRT's advocates also point out the project could be completed in phases, gradually improving service until completion. (Port Authority is considering whether the BRT could terminate in Shadyside or Squirrel Hill.)

The project could shave travel times between Morewood Avenue near Carnegie Mellon and Downtown to just over 14 minutes. That trip currently takes between 23 and 33 minutes, according to the proposal.

But the BRT project "[isn't] just about the time," Fitzgerald says. It's about spurring development in places like Uptown, which has plenty of property close to Downtown that could be attractive to developers.

"We realized there would be a significant amount of development that will occur; property values will go up," Fitzgerald says.

Ken Zapinski, vice president of energy and infrastructure at the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, agrees. "It's an economic development/transformation project that happens to have transit as a component."

He says public-private partnerships will be crucial in funding the project, especially given increasingly competitive federal funding. "We cannot use Washington and their procedures or lack of money as an excuse not to improve our transit system," Zapinski says.

And though the Port Authority is seeking federal grant money, it would likely get no more than $75 million — a reality, Fitzgerald acknowledges, that will require a "significant amount of local match."

In late 2011, Wanda Wilson joined the stakeholder group tasked with assessing whether a BRT plan should move forward, though she says BRT in the Oakland-Downtown corridor was the only transit project up for discussion.

The Allegheny Conference, Hill District Consensus Group, Pitt and CMU are among the nearly 50 organizations that have participated in the stakeholder group.

"It's a good group in terms of its makeup," says Wilson, executive director of the Oakland Planning and Development Corporation. But "it kind of started from [...] the assumption that bus rapid transit would be the best way to improve transit in this corridor." BRT might be the right idea, Wilson says, or the answer "might be a [rail] line that goes underground."

Members of the Uptown community have also expressed some skepticism over the value of BRT.