Former employees of the Sheridan Broadcasting Network have yet to see a penny from a $240,000 court judgment issued last year following a long fight for unpaid wages and severance payments.

Eleven former staffers of the now-defunct, Pittsburgh-based network say they were abruptly terminated in 2017 without their final paychecks or the severance payouts spelled out in their union contracts. Several reportedly struggled for years to find new work.

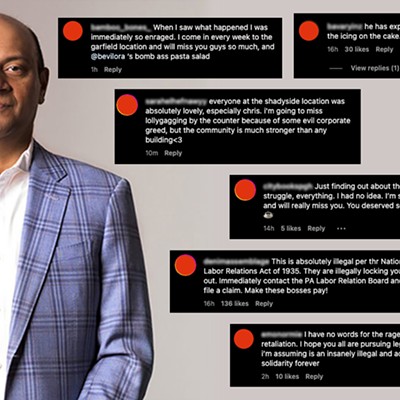

Sensing an impasse five years along, the group is now appealing to the public and current affiliates of owners Ron Davenport Jr. and Ron Davenport Sr., who remain active in Pittsburgh media circles.

“The victimized workers are outraged by the bad business behavior of the Davenports, who continue their radio business and have the gall to retain board seats with media companies like Block Communications (owner of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette) and Mellon Private Asset Management, to name a few,” the employees wrote in a recent press release. “The former employees are calling on these companies and others associated with the Davenports to urge them to pay their debts out of a sense of common decency if nothing else."

When the employee’s union, SAG-AFTRA, filed a suit to reclaim the unpaid wages, they initially secured a judgment that would hold the Davenports individually liable if the company did not or could not pay. Sheridan appealed this, and in February 2021, a judge confirmed the underlying claims against the company but determined the Davenports were not personally responsible for making the payments.

The employees say they’ve stayed silent until now on the advice of their union, but they remain committed to claiming what they’re owed.

Ty Miller, a former SBN director, says he was pushing to go public early on and is frustrated he and his colleagues chose to wait five years.

“What boggled my mind at the time was, 'Why didn’t we go public with the money that was owed?'” Miller says. “Why not say someone owes you money publicly?”

He adds that he hasn't "given up the belief that I’ll be getting paid by some form or another."

The union maintains it has fought for the employees since the beginning and is continuing to pursue the judgment.

“SAG-AFTRA has pursued every viable legal avenue to compel Sheridan to comply with their contractual obligations,” says a union spokesperson in an email statement. “We have also tried to keep the affected employees up to date on the process. Unfortunately, Sheridan's deliberate, egregious and anti-worker actions have forced the union to use the legal process, which has not moved quickly, and Sheridan has taken full advantage of the process to keep its former employees from receiving the compensation that they have earned.”

Reached by phone, Ron Davenport Jr. declined to comment. Lawyers representing Sheridan did not return email inquiries.

Once a major player in Black radio nationally, Sheridan Broadcasting Corporation owned urban local stations WAMO-FM, WAMO-AM, and WPGR-AM until it sold them to Westmoreland County's St. Joseph Missions in September 2009. (WAMO had since been purchased by Martz Communications Group which sold it to Audacy in March 2022.)

Sheridan was then forced to give up its 51% share of the American Urban Radio Networks in 2016, following a lawsuit launched by junior partner National Black Network. Following the dissolution, the company maintained four newsrooms, including SBN in Pittsburgh and others in Georgia, New York, and Alabama. SBN was shuttered a year later.

Some employees said their pain and frustration were compounded by the trust they once placed in their former employers.

“It is the principle because I feel like we were a very small shop. … We all were like family, even with the Davenports,” says former SBN reporter Allegra Johnson. “I feel like you wouldn’t do that to family.”

Johnson says after being laid off, it took her a year to find new work as a communications director during which time she had no severance pay to fall back on. She said other former colleagues struggled for even longer amid a declining media economy.

“Some of us are only now getting jobs,” she says.

Miller, who joined the network in 1990, sees the Davenports’ choice to wage a legal campaign while denying the payouts as a demonstration of bad faith.

“They’re paying someone not to pay us,” he says.