Confusion grows over funding sources of meal-delivery programs

“I’m afraid whatever happens, it’s not going to be good."

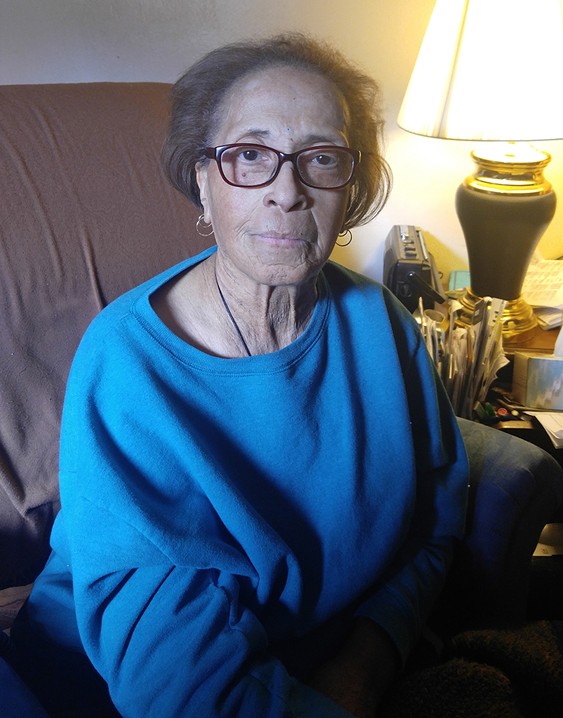

Karen Stanton of Lawrenceville says she heard on the news that the funding for her thrice-a-week meal deliveries is in jeopardy. A senior citizen who has trouble getting around, Stanton is one of 250 people in eastern city neighborhoods served by Catholic Youth Association’s meal-delivery program, which most refer to as “Meals on Wheels.”

So when the Trump administration unveiled its budget that proposed cuts to Community Development Block Grants, which some states use to fund Meals on Wheels or similar programs, a lot of people connected the dots to suggest Meals on Wheels was in jeopardy.

But Catholic Youth Association’s meal delivery would not be directly affected by CDBG cuts. It’s one of the nine meal-delivery programs administered by the Allegheny County Area Agency on Aging (which, with the Pittsburgh accent becomes “Mills on Wills").

The majority of the Agency on Aging funding for meal-delivery programs comes from the Pennsylvania Lottery, with a small portion coming from other federal sources, says program administrator Marion Matik. As long as Pennsylvanians keep playing the lottery, “these programs are relatively safe” from budget cuts, Matik says.

The Agency on Aging contracts with community organizations to get the meals out, including Catholic Youth Association; Eastern Area Adult Services, in Turtle Creek; the Hill House Association; Mollie’s Meals, via the Jewish Association on Aging in Squirrel Hill; Life Span, in Homestead; the Northern Area Multi-Service Center, in Sharpsburg; Penn Hills Senior Center; Plum Senior Center; and Riverview Community Action, in Oakmont.

To be sure, there are Meals on Wheels programs that would be affected if CDBG funds were reduced or cuts. The Meals on Wheels program in the city’s Brookline neighborhood, for example, receives about 20 percent of its budget from CDBG grant funds.

While CDBG grants are not the majority source of funding for most Meals on Wheels programs — that distinction belongs to the Older Americans Act Nutrition Program, overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services— the grants are vital to those programs that do use them.

“Cuts of any kind to these highly successful and leveraged programs would be a devastating blow to our ability to provide much-needed care for millions of vulnerable seniors in America, which in turn saves billions of dollars in reduced health-care expenses,” Ellie Hollander, president and CEO of Meals on Wheels America, said in a statement.

CDBG grant cuts would also have an impact on about four dozen other social programs in Pittsburgh. The city’s 2017 budget includes about $12.5 million in CDBG funds. Organizations like the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank and the Pittsburgh Women’s Shelter would be left with funding gaps if CDBG funds were reduced or eliminated.

But among area seniors, there’s confusion about whether the meal-delivery programs are going away.

“I couldn’t get by without it,” says Frank Kline of Lawrenceville. He lives alone, and has trouble navigating steps.

The Catholic Youth Association program, which is run out of the Stephen Foster Community Center in Lawrenceville, delivers two meals per customer three days a week (and adds frozen meals for the weekends, if needed).

The drivers also do safety checks on the seniors receiving the meals, says Catholic Youth Services Executive Director Gretchen Fay. This could mean everything from making sure a senior is in good health, to helping them bring in garbage cans, to changing a lightbulb so the senior doesn’t have to climb a ladder.

The morning preparation routine in the community center kitchen is impressive to behold. About a dozen drivers and runners put together the meals from food delivered by Ambridge catering company Metz Culinary Services.

Payment is not required, but some meal recipients make small donations. Most of the staff are senior citizens themselves, and for many of the meal recipients, their meal delivery may be the only interaction they’ll have with another person that day.

“It could be a small interaction, maybe 30 seconds, but they get to trust you and you get to know them,” says driver Mark Lewandowski. “You can’t put a monetary figure on that. It’s not just a budget item.”

For Rich Yost, 80, his motivation for being a meal-delivery driver was simple: “I just wanted to take care of old people,” he says with a wink. Yost drives a regular route with runner Karen Kahler. She brings the food to the door, and he navigates the route they travel three days a week.

Kahler, whose father is 85, says she’s always worried about the uncertainty around social programs that affect the elderly. “Eventually we’re going to get there too,” she says. “These people can’t get around, and they worked all their lives. They deserve to be treated better.”

For her part, Stanton says she thinks the Trump administration’s budget looks bad in general for low-income people and children. But she isn’t surprised.

“The sad part about the whole thing is everyone who helped put him in [office] is hurting,” Stanton says of the president. “I’m afraid whatever happens, it’s not going to be good. He doesn’t know what it means to need something.”

So when the Trump administration unveiled its budget that proposed cuts to Community Development Block Grants, which some states use to fund Meals on Wheels or similar programs, a lot of people connected the dots to suggest Meals on Wheels was in jeopardy.

But Catholic Youth Association’s meal delivery would not be directly affected by CDBG cuts. It’s one of the nine meal-delivery programs administered by the Allegheny County Area Agency on Aging (which, with the Pittsburgh accent becomes “Mills on Wills").

The majority of the Agency on Aging funding for meal-delivery programs comes from the Pennsylvania Lottery, with a small portion coming from other federal sources, says program administrator Marion Matik. As long as Pennsylvanians keep playing the lottery, “these programs are relatively safe” from budget cuts, Matik says.

The Agency on Aging contracts with community organizations to get the meals out, including Catholic Youth Association; Eastern Area Adult Services, in Turtle Creek; the Hill House Association; Mollie’s Meals, via the Jewish Association on Aging in Squirrel Hill; Life Span, in Homestead; the Northern Area Multi-Service Center, in Sharpsburg; Penn Hills Senior Center; Plum Senior Center; and Riverview Community Action, in Oakmont.

To be sure, there are Meals on Wheels programs that would be affected if CDBG funds were reduced or cuts. The Meals on Wheels program in the city’s Brookline neighborhood, for example, receives about 20 percent of its budget from CDBG grant funds.

While CDBG grants are not the majority source of funding for most Meals on Wheels programs — that distinction belongs to the Older Americans Act Nutrition Program, overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services— the grants are vital to those programs that do use them.

“Cuts of any kind to these highly successful and leveraged programs would be a devastating blow to our ability to provide much-needed care for millions of vulnerable seniors in America, which in turn saves billions of dollars in reduced health-care expenses,” Ellie Hollander, president and CEO of Meals on Wheels America, said in a statement.

CDBG grant cuts would also have an impact on about four dozen other social programs in Pittsburgh. The city’s 2017 budget includes about $12.5 million in CDBG funds. Organizations like the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank and the Pittsburgh Women’s Shelter would be left with funding gaps if CDBG funds were reduced or eliminated.

But among area seniors, there’s confusion about whether the meal-delivery programs are going away.

“I couldn’t get by without it,” says Frank Kline of Lawrenceville. He lives alone, and has trouble navigating steps.

The Catholic Youth Association program, which is run out of the Stephen Foster Community Center in Lawrenceville, delivers two meals per customer three days a week (and adds frozen meals for the weekends, if needed).

The drivers also do safety checks on the seniors receiving the meals, says Catholic Youth Services Executive Director Gretchen Fay. This could mean everything from making sure a senior is in good health, to helping them bring in garbage cans, to changing a lightbulb so the senior doesn’t have to climb a ladder.

The morning preparation routine in the community center kitchen is impressive to behold. About a dozen drivers and runners put together the meals from food delivered by Ambridge catering company Metz Culinary Services.

Payment is not required, but some meal recipients make small donations. Most of the staff are senior citizens themselves, and for many of the meal recipients, their meal delivery may be the only interaction they’ll have with another person that day.

“It could be a small interaction, maybe 30 seconds, but they get to trust you and you get to know them,” says driver Mark Lewandowski. “You can’t put a monetary figure on that. It’s not just a budget item.”

For Rich Yost, 80, his motivation for being a meal-delivery driver was simple: “I just wanted to take care of old people,” he says with a wink. Yost drives a regular route with runner Karen Kahler. She brings the food to the door, and he navigates the route they travel three days a week.

Kahler, whose father is 85, says she’s always worried about the uncertainty around social programs that affect the elderly. “Eventually we’re going to get there too,” she says. “These people can’t get around, and they worked all their lives. They deserve to be treated better.”

For her part, Stanton says she thinks the Trump administration’s budget looks bad in general for low-income people and children. But she isn’t surprised.

“The sad part about the whole thing is everyone who helped put him in [office] is hurting,” Stanton says of the president. “I’m afraid whatever happens, it’s not going to be good. He doesn’t know what it means to need something.”