On a particularly chilly evening in February, about 14 residents are gathered in the basement of the Church of the Holy Cross in Homewood. It has all the usual trappings of a neighborhood meeting: plastic folding chairs, linoleum floors, drop ceilings and some sandwiches spread across a table in the corner — an incentive to show up despite the elements.

But what's going on at this meeting is hardly typical. After a several-minute crash course in urban planning, Operation Better Block (OBB) asks Homewood residents to put aside differences and re-think their neighborhood, one property at a time.

"There are people in the community who want to be involved in what's happening," explains OBB executive director Jerome Jackson. "But no one has really made it accessible to them."

That's changing, Jackson says. Over the past year-and-a-half, OBB has invested in an ambitious "cluster planning" process in which Homewood residents are responsible not only for coming up with a detailed plan for revitalizing their neighborhood, but are also charged with making sure those plans don't sit on a shelf collecting dust.

Just outside the church on Kelly Street, it's obvious change is needed: There are overgrown vacant lots next to boarded-up houses, and slabs of sidewalk that have gone unmaintained and have erupted into the air, like warring tectonic plates. A few blocks away next to a crumbling stoop, a sign reads: "STOP SHOOTING Live Love Respect."

These are symptoms of larger problems, but OBB isn't looking to rehash the challenges everyone already knows about. They're asking people — who have been invited because they all live within a few blocks — to roll up their sleeves and try to reach consensus on everything from what property should be demolished to where a new playground might succeed.

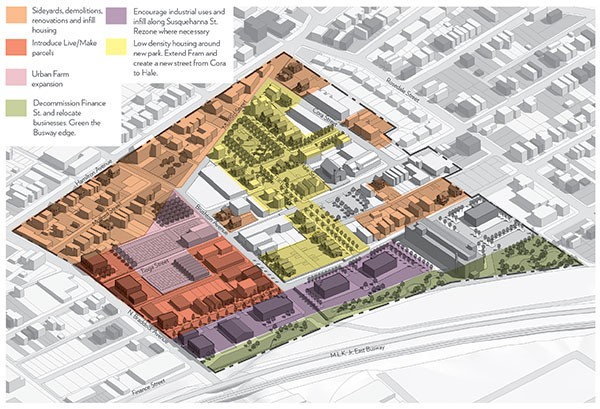

It's a painstaking process. From January 2014 to summer's end, OBB will have held roughly 30 community meetings, drawn up more than a dozen different land-use plans and knocked on every door in the neighborhood for input at least three times. They will have formed roughly 10 distinct "cluster associations," each responsible for carrying out its section of the neighborhood's consensus plan.

The process, which cost roughly $63,000 not including OBB staff time, was largely funded through the Richard King Mellon foundation, while the Pittsburgh Foundation contributed funds for an original effort to survey each of the neighborhood's properties, says Demi Kolke, who is leading the cluster-planning project. She notes that all of the cluster plans have been completed except one.

But not everyone in the neighborhood is on board. OBB is facing some skepticism from other community groups and residents, some of whom feel like they never agreed to OBB's approach and shouldn't be bound by its "consensus." And even among those who support the process, concerns linger about whether developers and property owners, including the city, will pay much attention to it.

"The confusion comes with the residents when they hear they're supporting something and all they know is that they participated and they signed an attendance sheet," says Dina Blackwell, co-founder and CEO of the Homewood Renaissance Association. Just "because you're in attendance, doesn't mean you agreed."

Still, almost everyone acknowledges the neighborhood is going to change; the question is how much control residents will have over it.

"The development is coming," says Emmett Wilson, who has attended OBB's cluster-planning meetings and points to its easy access to the busway and flat terrain. "They're preparing Homewood for change ... I'd just like to see the residents involved."

Born in Homewood 46 years ago, Wilson is perched over a map of "cluster five" — a several-block quadrant in the middle of Homewood that contains the 13 apartment units he rents out.

He has a green dot sticker in his hand and places it on a plot of land near Bennett Street marked "small apartments." He explains that building new apartments could "bring in people from outside the community to live side by side."

This is essentially what the cluster-planning process looks like: residents gathered around hyper-localized maps that each represent about one-tenth of the neighborhood. At each of three community meetings spread over a few weeks, they're asked to mark up the maps with ideas about how to use the vacant land.

The reason OBB divided the neighborhood into 10 distinct clusters, each with three set community meetings, is to "include people who would probably not engage in the traditional planning model," Jackson says. The typical process, he notes, is to invite people to one neighborhood-wide meeting — a practice that inevitably leaves people out who can't make it.

And since each cluster contains roughly 225 occupied parcels, it's possible to knock on every single door and invite people to the meetings specific to their cluster. Residents are guided by planning consultants from Studio for Spatial Practice, who lend expertise on zoning rules and best practices in planning. In between meetings, the same consultants turn the recommendations into draft land-use plans. Those plans are mailed to every resident in the cluster, who are invited in person by volunteers to attend the next meeting. Finally, the plan is resubmitted to residents for edits and approval.

"[OBB's Jackson] was explaining it to me and I was like, ‘Damn, man, that's a lot of legwork,'" says Henry Pyatt, the City of Pittsburgh's small-business and redevelopment manager, who says he has rarely seen so much effort devoted to soliciting resident input. "It makes it really easy for me and other organizations in Homewood to guide developers. ... We can say, ‘Here's the plan; here's what the community wants.'"

OBB has drawn a higher-than-expected 615 unique participants to attend cluster meetings (about 10 percent of the neighborhood population) But the group acknowledges the neighborhood won't change overnight. Jackson, for instance, notes that there hasn't been a house built and sold in Homewood without a government subsidy since 1998.

An interconnected web of disinvestment, vacancy issues and public-safety concerns all pose challenges, says OBB's Kolke. Of the 5,160 parcels in Homewood, 61 percent are vacant, she says. And for the past 70 years, the neighborhood has experienced significant population loss. The neighborhood went from a population of 31,000 in 1940 to about 6,442 in 2010.

But there have been bright spots in Homewood's recent past.

"Beginning in the mid-'80s to the very early '90s ... Homewood was becoming a very good example of revitalization," says Mulu Birru, who served as the executive director of the city's Urban Redevelopment Authority from 1992 until 2004 and was a director of the Homewood Brushton Revitalization and Development Corporation, before it went defunct.

The HBRDC successfully attracted development to Homewood Avenue, Birru says, drawing on revitalization that was happening in North Point Breeze. "It just went down after that," he says. "The apartments were not maintained, the Dairy Queen shut down ... I think crime was one [reason]."

Another reason, he says, is that despite "great" community leaders, "you need a professional staff to carry that mission."

That's a legacy OBB is well aware of. "The biggest challenge was just the lack of belief in OBB, community planning, in the revitalization of Homewood," says Kolke. "People have been promised many things ... their hopelessness is justified."

That's one of the reasons for the creation of "cluster associations" — groups of interested residents facilitated by OBB who will do everything from notifying 311 problem properties to negotiating directly with developers. The idea is to make sure the focus isn't just on lofty long-term goals, Kolke says, but short-term projects residents can work on right away.

"The low-hanging fruit will be to develop green space and initial cleanup," says 44-year-old Bob Lee, a Homewood resident involved in his newly formed cluster association. He says his association has already started meeting with developers who have expressed interest in building apartments.

Asked how optimistic he is about the process, he says: "I think it's good to have something on paper, [but] I'm on the fence. I have no idea if what we say is actually going to happen. We don't own any of this [land]."

Carl Redwood, chairman of the Hill District Consensus Group, also cautions against holding a sanguine view of Homewood's future.

"The real issue is, how do you take the plan done by residents and force politicians Downtown to honor it and support it?" Redwood asks. "I'm not trying to throw shade on the OBB process. It's one of the best processes you could use to move forward. I just don't want to lose sight of what's happened already: large displacement of black people."

One way to avoid that history, some argue, could be the city's land bank — a quasi-government entity approved last year that is designed to serve as a clearinghouse for publicly owned blighted and vacant property. (Roughly one-third of Homewood's vacant land is publicly owned as of 2010, Kolke says, and 93 percent of those parcels are held by the city or URA.)

"We have what appears to be a model inclusive planning process," says Helen Gerhardt, who serves on the housing committee on the Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations, but was not speaking on behalf of the organization. "Whether we have processes that give those plans teeth," she said of the land bank's yet-to-be-determined policies and procedures, "that's going to be crucial."

So far, at least, the cluster-planning process appears to have government support. Cluster planning is "something we support at the URA," says Karen Abrams, community- and diversity-affairs manager, who notes that OBB's individual work with residents can also help link them to social services. "We definitely need to figure out better ways of engaging communities around planning."

For the city's part, Pyatt says, cluster planning is a model he'll "push" for in other neighborhoods when it's appropriate. But he stresses the importance of being realistic about the pace — and consequences — of change. "I'm under no illusion we're going to build every single building," that was drawn in a cluster plan, he says.

And because development is driven in part by private dollars, "we're trying to match the market with community desires," Pyatt says. "It's about finding a compromise. ... Our mantra is ‘development without displacement,' [but] as prices rise, some folks are inevitably going to be displaced."

And while most people in community-development circles lauded OBB's efforts, some expressed skepticism of its approach. The Homewood Renaissance Association's Blackwell, for instance, says she's heard residents wonder whether their mere attendance at a cluster meeting signals that they must agree with it. "Is this being considered the master plan? There's just a lot of questions," Blackwell says, noting that she doesn't want to "[take] away from the hard work and booklets and outreach."

OBB's Jackson has heard some of these concerns. "We've gotten some pushback from gatekeepers," he says. "It really is about the old, traditional model. We have a group of people who sit around a table and make decisions, then convince the community of that decision."

"We don't want to be the voice of residents," he adds. "We want to give residents a voice."