On a spring day in 1992, a 16-year-old boxing prodigy named Paul Ross Spadafora walked into the Island Avenue Tattoo shop in McKees Rocks. Weeks before, he'd dropped out of his sophomore year at Sto-Rox High School to focus on boxing. But Spadafora wanted to demonstrate his commitment to the sport even more dramatically.

A natural righty who fought as a left-hander, he asked to have a paw-print tattooed on his upper stomach, with the word SOUTH inscribed above it.

His older brother, Harry, had told Paul that Island Avenue's tattooist, Nick Bubash, "was the best around." But Paul's trainer and mentor, Charles "P.K." Pecora, was not impressed -- despite having a set of tattoos of his own dating back to his days in the Navy.

"He didn't like it," Paul Spadafora recalls with a laugh. "He said, 'Quit doing that stuff to your body. You're supposed to come across as an old-school Italian fighter.'"

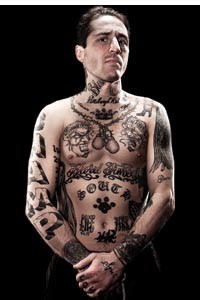

But by then, Spadafora was already winning regional titles in the 125-pound weight division. And the "southpaw" tattoo was just the first of 24 that Spadafora would have inscribed on his upper body over the next 17 years. Together, they serve as reminders of all he had and lost -- and all he still hopes to gain. They mark his rise from street tough to promising amateur boxer to world champion. And they illustrate his fall from grace, his struggles with alcoholism, and a prison term served for shooting his girlfriend. Most of all, they inspire his hopes of regaining the lofty perch he once held.

The next step up that hill will take place in late January, when he fights a still-undetermined fighter in Miami. Though the opponent isn't expected to be a ranked contender, Spadafora's promoter, Mike Acri, hopes this fight will put him closer to a serious fight later in 2010.

"Shakespeare would have a ball with his story," says longtime friend Jimmy Cvetic, a local boxing organizer and poet. "It's fate and chance together."

But on that day in 1992, Paul's body was an empty canvas.

"He was just a quiet, thoughtful kid then," says Bubash, who has inked nearly half of Spadafora's tattoos (and who now does his inking at Route 60 Tattoo). Today, "He wears his history on his body."

And at age 34, he's once again trying to stake his future on it too.

Lots of boxers have tough childhoods. Spadafora's was worse than most.

His father, Silvio Spadafora, was a drug addict who died of an overdose when Paul was 9. Harry, who was just 12 then, found the body at their home in Heidelburg, where their father taught gym at their school, St. Ignatius.

Their parents had divorced, and the boys had been living with their father because two years earlier, their mother's boyfriend -- the father of their half-brother, Charlie -- had shot at their house during a fight.

With their father dead, they ended up back with their mother, Annie. She moved around a lot, from the North Hills to Sheraden, to Millvale, and finally to the McKees Rocks neighborhood known as The Bottoms, a hard-knock area of town near the railroad tracks along the Ohio River.

Paul and Harry agree that their mother had her own problems. When her house was calm, they stayed there. When it wasn't, they found somewhere else to stay: a friend's, a neighbor's, even sleeping outside under someone else's porch.

"He would sleep over at my house sometimes. I never asked why," says Belia Cercone, the grandmother of one of Paul's best friends.

"Yeah, we had some bad times," Spadafora recalls. "But there was a lot of good, too, you know? I have a lot of friends from then."

"Harry raised him because they grew up on the street," says his step-aunt, Ann Spadafora, who is married to the uncle after whom Paul is named. "Harry was the one who had to find food for them sometimes."

And Harry was the one who introduced his younger brothers to boxing.

"I was getting in a lot of street fights," Harry recalls. "One of my mom's boyfriends, who'd been a professional fighter, saw that and took me to Jack's" -- a boxing gym in Pittsburgh's Hill District.

Harry started boxing when he was 15. Paul began fighting a year later, at age 12. It was one of the few family traditions they could still hold onto. Their maternal grandfather, Eugene Pelecritti, had been a former boxer, and "Pap" would be a lifelong influence on Spadafora. (His 4-year-old son, Geno, is named for Pap.)

Boxing gave them both some badly needed stability. "Boxing saved me for a long time. It taught me discipline. Paul too," says Harry.

Most importantly, boxing brought Spadafora into contact with P.K. Pecora. The initials stood for "Pittsburgh Kid," a nickname previously given to 1940s-era boxer Billy Conn, and later bestowed on Pecora when he was a young fighter. Later, the nickname would be attached to Spadafora as well -- and that's not all Spadafora inherited.

"He was my father figure," Spadafora says. "He was someone who never would shut the door on me."

"My other kids call him our 'other kid,'" says Rachael Pecora, P.K.'s wife. Spadafora was a regular guest at the Pecora home, and P.K. "kept Paul in line. He was the only one who could." Even at an early age, Spadafora "used to drink that doggone beer, but P.K. would straighten him out."

By 1994, Paul was a rising amateur, regularly winning Golden Gloves tournaments at the same time his brother, Harry, would win the heavier, 156-pound category. Cvetic, who likes to say he knew Paul "before the tattoos," says Pecora would regularly tell him in those early days: "This kid is going to be a champion."

"I thought his brother, Harry, was better," Cvetic admits. "Paul was just a little guy. But P.K. would say, 'No, he's the one.'"

Together, Pecora and Spadafora mapped out a plan for becoming a champion. It relied on a boxing style that avoided getting into slugfests, one that instead stressed Spadafora's technical skill, speed and agility.

But even as Spadafora developed finesse inside the ring, he was starting to trip himself up outside it.

On the night of Dec. 24, 1994, police spotted Spadafora and some underage friends drinking and driving. The driver tried to flee, and ended up hitting a telephone pole. At some point, a police officer fired at the car and the bullet lodged in Spadafora's left leg. The injury derailed any hopes Spadafora had of making the 1996 Olympic boxing team.

"It was stupid. And all because of drinking," Spadafora recalls, shaking his head. After a two-week hospital stay, "The doctor said I might never fight again."

But Spadafora refused to accept that possibility. He sought out another tattoo, this one a thorn-necklace-and-boxing-gloves tattoo inscribed on his chest -- an inspiration "to push me to focus more on fighting."

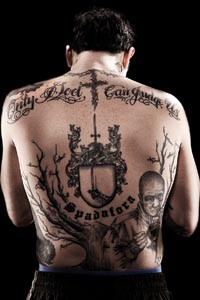

"Every morning when I'd look in the mirror, that's what I'd see," Spadafora says. "The thorns are like the crown Jesus had, and with the cross on my back -- it's all part of my struggle."

Eight months later, Spadafora was arrested again, this time for underage drinking. But by September 1995, with nine months of intense therapy and Pecora reminding him of how he had screwed up, his leg had healed. Too late to earn a spot on the Olympic team, he turned pro.

Spadafora fought 18 more times over the next three years, winning 10 of his matches by knockout. Finally, he got his big shot: an Aug. 20, 1999, bout against Israel "Pito" Cardona for the International Boxing Federation's world lightweight title.

With a 31-2 record, Cardona was the favorite. But the bout, held at Mountaineer Racetrack, went the full 12 rounds, with Spadafora outscoring Cardona in each.

Cardona and his trainer, John Cipolla, still suspect it was an unfair fight.

"It just seemed like his hand-eye coordination was almost over-human," says Cipolla. "In my view, he was helped."

Cipolla has no evidence that Spadafora used performance-enhancing drugs, but he and Cardona note that no drug testing was done before or after the fight.

"In a world title fight, the fighters always get drug-tested, right? But we didn't," says Cardona. "The pee-pee doctor didn't come see us for some reason."

Spadafora's camp laughs off the accusations.

"There were no drugs. He was just the better man," says Harry, who has attended all of his brother's professional fights. "He was fighting with that spirit, and Cardona wasn't."

With the win, 23-year-old Paul Spadafora became the first Pittsburgher to wear a title belt since Billy Conn became a light-heavyweight champ in 1939.

But P.K. Pecora hadn't lived to see it. He'd died in 1997, at age 68, the victim of a stroke. (Spadafora barely had time to mourn: The funeral came just two weeks before another fight.) Pecora had guided him to a championship, but for Spadafora, that would prove to be the easy part. He'd soon be wealthier than any kid from The Bottoms could ever dream of becoming ... but he no longer had his mentor to help him cope with the fickle nature of boxing success.

"That loss changed my life," says Cardona, whose career has been on the wane ever since (though he still harbors faint hopes of squaring off with Spadafora again someday). "The sport has not been good to me ever since I lost the world-title bout."

In fact, he adds, "For both of us, it was bad."

Over the next four years, Spadafora defended his belt 10 times, earning millions along the way.

Some of his opponents were worthier than others, but "he was a good champ. He wasn't dodging anybody," says John Taylor, who was the trainer for Angel Manfredy, at the time a ranked contender whom Spadafora beat by unanimous decision in March 2002.

"You can't outbox Paul Spadafora; he's a boxer, not a puncher," Taylor says. "I kept telling Angel, 'Get in there, man, and break his leg. You can't outbox him. You have to rough him up.' But he couldn't get to him."

In late 2002, Spadafora won a second belt, earning the International Boxing Council's title with a victory over Dennis Holbaek Pederson. He became a favorite of the HBO Saturday-night boxing series. He had a steady girlfriend for much of the time, Crystal Connor. And he became a father twice over.

But the quiet, thoughtful kid who walked into Nick Bubash's tattoo shop in 1992 had also become increasingly brash.

"I remember in the pre-fight, he was telling me, 'I've got a black woman.' Yeah, well so do I," recalls Taylor, who is black. "He seemed like he wanted you to know he was a young fly guy. He wanted people to know he was too hip."

Spadafora remained in McKees Rocks, but with an average of six months between fights, he began a pattern of splurging and purging. He was the life of a non-stop party, and his weight would sometimes balloon to 155-160 pounds. Frequently, his pre-fight training regimen included dropping 20 pounds or more to make weight.

Meanwhile, the money and fame attracted an entourage of hangers-on and yes-men, who did everything they could to encourage his excesses.

"We were told that people who wanted things from Paul would get him drinking and then he would sign whatever they wanted," his step-aunt, Ann Spadafora, says. "He was under the influence of the wrong people and he just blew it."

"I remember all that money," says Harry Spadafora. "I mean, you're talking millions of dollars all the sudden in his bank account, and he was giving it to street people, friends, people he barely knew -- all because he's a good guy."

"I was letting other people decide who I was, you know what I'm saying?" Paul Spadafora recalls of those days. "You've got to find what you need to do, who you want to be. I wasn't doing that."

Partly that's because during his championship run, Spadafora lost a second father figure: In the years following Pecora's death, Spadafora began to rely increasingly on his grandfather's support and guidance. But in 2001, Pap died as well.

"If Pap was here, I wouldn't have gotten into this trouble," says Spadafora, who has three tattoos honoring his grandfather.

Spadafora's fans are haunted by such possibilities. What if Spadafora hadn't lost his mentors so early in his career? Could Pecora have kept Spadafora out of trouble?

"I don't know," says Harry. "But I know Paul would already be thought of as the best 140-pound boxer who ever lived by now if he did."

The beginning of the end came on May 17, 2003.

Spadafora was challenging Leonard Dorin, hoping to claim his third championship belt, Dorin's World Boxing Association lightweight title. But Spadafora could manage only a draw, the first blemish on a boxing record composed of 36 wins.

Things fell apart quickly. During the months that followed, two members of Spadafora's inner circle, trainers Tom Yankello and Jesse Reid, were ousted.

Spadafora is reluctant to discuss that chapter, even today. "It was just a bad situation," he says. Yankello and Reid "didn't get along with everyone, and I had to make a change."

Meanwhile, Spadafora was having so much trouble making the lightweight limit that he switched to the heavier junior welterweight (140-pound) division. His promoters began seeking a fight against one of the division's luminaries, a fight that could have been Spadafora's first million-dollar payday. But on Oct. 24, 2003 -- just days before he was due in training camp -- Spadafora was arrested in Downtown Pittsburgh instead, for public drunkenness and urinating in the street.

Cvetic was among those who went Downtown to see if they could get Spadafora released.

"It crossed my mind that maybe I should let him sit it out in there," acknowledges Cvetic, who is a retired narcotics detective. "But I talked to the judge and got him" released. "I wish I hadn't."

Two days later, early in the morning on Oct. 26, 2003, Spadafora was out drinking again -- this time with his then-girlfriend, Nadine Russo.

By this point, Spadafora's license had been suspended for another drinking-related offense, so Russo was driving his Humvee H2. And when she turned into the BP Gas Station, located just off the McKees Rocks Bridge, she hit the curb, blowing out two tires.

Spadafora flew into a rage and the couple fought outside the car. As Russo later testified, according to newspaper reports, in an attempt to try to scare Spadafora, she grabbed his gun from her purse in the car. While they fought over the gun, she said, it went off, striking Russo in the chest.

"Like the time I got shot, it was because of alcohol," Spadafora says today. "Because of that, I hurt someone I love and it changed my life -- our life -- forever."

Russo recovered and she and Spadafora reconciled. A little more than a year after the shooting, the two had a child, Geno, and even planned to get married. But their volatile relationship fell apart, and Russo also landed in some trouble of her own. Last year, she was charged for allegedly taking part in an insurance scam. She also stands accused of distributing cocaine.

(Geno is being raised by a family friend as Russo awaits resolution of her case. She could not be reached for comment: She had been staying with her father, John, but when reached by City Paper, he refused to discuss her whereabouts. "I don't want to be any part of that," he said before hanging up the phone.)

As a result of the 2003 shooting, Spadafora was charged with attempted homicide as well as aggravated assault, reckless endangerment and unlicensed possession of a firearm. The next year, Spadafora pleaded guilty to aggravated assault, and spent seven months in prison and six months in boot camp.

Edward J. Borkowski, the Allegheny County prosecutor who handled Spadafora's case and is now a county judge, says Spadafora's problems went beyond alcoholism: "I don't think he could figure out early on who was in his corner for Paul Spadafora-the-guy-from-McKees-Rocks" -- as opposed to "Paul Spadafora-the-boxer-who-any-hanger-on-could-take-advantage-of."

At bottom, Borkowski says, Spadafora's problem was "success -- too much, too soon."

Ann Spadafora agrees.

"He was just so focused when he was younger on what he wanted to be," she says. "Then when he got there, he didn't know where to go."

And then, Paul Spadafora -- the street kid who lost all three father figures in his life -- was forced to spend 13 months thinking about that, instead of trying to forget it with drugs and alcohol.

"I thought it was over, my career," Spadafora says of his time in prison. "I know that me and alcohol don't agree. I can't put that in my body because it doesn't do well with me.

"I promised myself, I'm not going to have that happen again."

Spadafora chose a by-now familiar way to make sure the lesson sunk in. After he got out of prison, he had his upper chest tattooed with the theater masks representing comedy and tragedy. "Smile Now / Cry Later," the inscription reads. It's a reminder of the price he has paid for his high living ... and of the fact that "as bad as it got, crying isn't going to help me."

Harry Spadafora, who has his share of tattoos as well, says, "My ex-wife used to say, 'You guys write all this pain on your body.' She's right."

In the six years since he shot Russo, Spadafora has fought just seven times, thanks in no small part to his prison stint. For a guy who fought in 10 title defenses in a little less than four years, that's working part time.

None of his seven post-shooting opponents have been contenders or even rising stars, just journeymen who can help prove that Spadafora is still worth fighting.

"I'd love to be in front of Mayweather," Spadafora says of the world welterweight world champion, Floyd Mayweather Jr., considered by many to be the best pound-for-pound fighter in the world. "I know that's talking crazy right now, but I know once I get my game back I can be there with him."

Boxing experts say that's a long shot, partly because Spadafora is in his mid-30s, when most fighters are on the decline.

"What it's going to come down to is: Can he perform at a certain level?" says Teddy Atlas, an analyst for ESPN2's Friday Night Fights, who called Spadafora's fight against Cardona in 1999. "People aren't going to line up around the block if he can't perform. And we don't know yet if he can."

But Spadafora does carry an added mystique: He has never been beaten. And adversity has never fazed him. "I mean, I got shot, man!" he says. "I got through that. I was away in the penitentiary. I had a lot of money, and then I was bum-busted ... and it was all over alcohol."

Spadafora's voice still carries some of the swagger he exhibited a half-decade ago, though his eyes no longer look so cocky. As his brother Harry puts it, "Pain and loss will make you humble."

But Spadafora has already outfought some of his demons. This past fall -- just about the time his parole for shooting Russo ended -- Spadafora turned 34. "My dad died at 33 years old, and I used to tell my mom that I was going to die at 33 too," he says. He even got a tattoo to remind him of his own mortality, complete with his birthdate and a blank space for a date of death. "My promoter, Mike Acri, was with me on my birthday and he was all over me: 'I told you you'd make it!'"

And his tattoos now serve as reminders of all he has to fight -- and to live -- for. His left forearm features a depiction of his oldest child, Giana. On the right, a picture of all three of his kids together.

To look at Spadafora, in fact, it's hard to see what he has left to prove. For one thing, his entire upper body is covered with tattoos -- with one exception. It's a four-inch-wide space on his right shoulder, just above the CHAMP tattoo and its index of the years he wore a championship belt.

Spadafora points to the space and says, without a hint of a smile, "That's where I'm going to put the year I returned as a champion."

[Editor's note: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the tattoo parlor where Paul Spadafora got his first tattoos.]