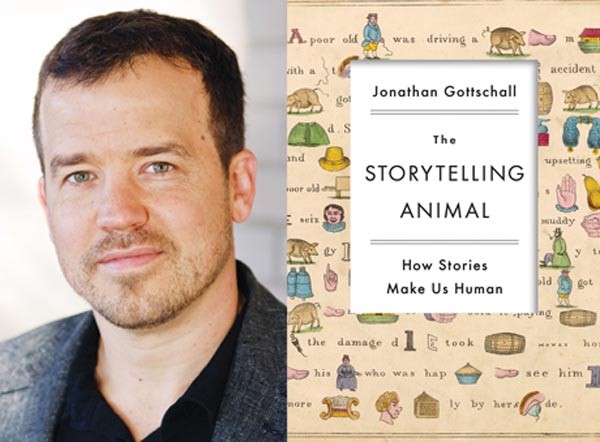

In his new book The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), Jonathan Gottschall explores the pervasive power of narrative through the lens of evolutionary psychology — that is, the adaptive advantages of human behavior. The critically acclaimed book doesn't deliver answers so much as ask provocative questions. And Gottschall, 39, who teaches at Washington & Jefferson College, has become a sought-after writer and speaker.

Gottschall's previous books include The Rape of Troy — an evolutionary-biology study of Homer — and his work has been featured in New York Times Magazine, Nature and Scientific American. He spoke with CP in June.

In your book, you ask not only how story works but what it's for. Why that approach?

Probably in the '90s, I was an English graduate student and I got interested in evolutionary psychology. And it sort of flipped around my way of looking at the world. It's really a nice discipline for making you think about those big fundamental questions about, well, why are things this way? Why are we this way?

Darwin used to say that when he looked at the peacock's tail, it made him want to vomit. It's like, why is that there? It doesn't make any sense in [Darwin's] theory; eveything should be strictly utilitarian. And you have this explosion of useless beauty in the peacock's tail. So of course he had to come up with a theory that it was sexual selection. And art is the same sort of thing — you have this explosion of useless beauty that takes a lot of time, a lot of energy, and if you're an evolutionist, you want to know why.

One theory you explore is that stories are little rehearsals for life.

We're in a period of fruitful speculation. A meaner way of saying that is we're in a period of generating just-so stories — which is usually a term of abuse. But a just-so story really is an evolutionary hypothesis. So we've made a lot of arguments, theorizing, specualtion, but we haven't gotten to the phase of attracting enough experimentalists — people who are actually clever about designing experiments to see which of these ideas is true.

The rehearsal idea is an idea that people have been triangulating on because the evidence seems kind of good from the perspective of dreams, and play, and fiction also. The thing that kind of brought me around to its plausibility was being really struck in my research by problem structure. It never really occurred to me to ask the question, why are stories so obsessed with trouble? Why are they so dark in many cases? Why are they always centered around problems and conflict and anxiety and stress and woe?

It's exactly the opposite of what you'd expect. People go into fantasyland — people say, "OK, I want to go into heaven. I want to go to a paradise that's all fried ice-cream, and sex, rainbows, whatever." But that's not what stories are like; those stories don't interest us.

That's one of the pieces of evidence for this sort of "simulator" idea, the idea that it's a rehearsal for the problems of human life, and that's why the stories are so problem-focused. But that idea may be wrong. There's other ideas that come up in the book that may be right. Or they may all be wrong: The whole thing could just be an evolutionary side effect; it could be for nothing at all.

What I hope the book will do is like draw attention to these poroblems, get other people speculating about it and ultimately start drawing in other experimentalists.

What about avant-garde narrative and other unconventional types of storytelling?

I think that's very cool, and I applaud that sort of thing. I think in the book I came off as being sort of anti-avant-garde-art. Maybe I was in a little bit of a cranky mood about it that day.

Finnegan's Wake comes up in the book — I really admire that book, I'm in awe of it, it's spectacular, the crazy commitment he had. Seventeen years of hell he spent on this book. But the crucial key is [people want to see] story. No one wants to read Finnegan's Wake. If I make a reference to that, even among literary scholars — "Honest to God, have you ever read that book?" — you know. And this is a book, when they do the poll, it's the 25th best novel of all time. And most literary scholars can't read it and won't read it.

It's interesting to me that [experimental narrative] does not reliably seize human attention and hold it. That's not a value judgment; I think it's a factual statement. You'll sit through four hours of Gone With the Wind, without your mind wandering at all. You'll sit through three hours of Avatar. Harry Potter's twice as long as War and Peace in its entirety. And we'll sit though it for hours on end, without our mind wandering. Nothing else in human life is capable of keeping our attention like that and holding it.

We have about 125 daydreams per hour. This is hard to even believe. But not when you're in a story. It's the one thing that's really capable of seizing and quieting the restless mind for significant amounts of time.

You note that story has conquered nonfiction realms like sportscasting: It's less game, more backstory.

I think producers, who've made it into a big broadcast phenomenon, have just figured out what priests have understood, and storytellers have understood: If you can wed your product to a narrative, to an emotionally rich narrative, with problem structure and with all those things, and put it into story format, you just do a better job of riveting human attention, of getting us emotionally absorbed in it, and ultimately attracting eyeballs and making money.

There's this insight, "Oh, we can get more people to watch if we weave it all into a story. And especially, we can broaden our demographics. Instead of just getting young men, who might be naturally drawn to this stuff, we can get housewives, we can get old ladies, if we can turn an Olympic broadcast into half sport and half lifetime television for women."

I'm incredibly frustrated by the extent of this when I watch the Olympics. All these soft-focus, fuzzy stories about these people's horrible dilemma that they've overcome in their lives. But it's very much playing into the universal grammar of storytelling.

What about story and politics?

In the '90s some time, the media began to ask consciously, "What's this candidate's story?" Not only their biographical story, but what's the narrative they want people to [heed].

It's almost like the contest isn't between the ideas or the politicians, but it's a story war.

When Kerry lost, in '04, I read James Carville saying, "Why did we lose? We lost because we had a list of things that we were going to make better: We're for the environment, we're for getting out of the wars, we're for social justice." The Republicans had a story [about] saving us from the terrorists in Tehran and the homos in Hollywood. Emotion. They really fired up their base emotionally and worked it into a story with bad guys — the homos in Hollywood, the terrorists — and good American heros.

But the best storyteller isn't necessarily the best leader.

It's hard to say that story's good or bad. What you can definitely say about it is, it's really, really powerful. It's a very good tool for the good guys,and it's a very good tool for the bad guys.

In advertising it's more pervasive still. You see these little stories even on beer labels.

They want to make clear they're not Budweiser. … I wrote a little short article about storytelling in business for Fast Company [Co.Create]. I think they called it, "Story — The Ultimate Weapon" or something. … I've been doing a lot of writing for blogs and promotional work for the book. It was probably the thing I wrote that took off the most. And it was because the business community is so incredibly receptive to those ideas. It got tweeted around like crazy. It really actually helped sales of the book a lot, in the short term at least.

It's almost reached a sort of faddish level in the business and corporate world, that if you don't have a story, you're dead. You need to have a story that defines your brand, defines your product, that helps you push your product.

Why is that?

The psychological research on fiction I get to in the book sort of suggests that we're pretty skeptical when reading nonfiction — we're critical, we're alert, we're on edge, knowing that we don't want to be manipulated, we don't want to be pushed around by believeing in something that isn't so. If you're against global-warming research and you think it's all bunk, and you read an essay that says, "Here's why you should believe that global warming is real and human-caused," the person's just going to dig in their heels. It's very, very hard to move anybody.

But if you work the same message into a story, say a disaster narrative about what's going to happen to the earth if things keep going along this way, you tend to get much more traction. This has been demonstrated in the lab. When [people] read fiction they drop their guard, they get a little softer, a little rubberier, a little easier to mold or manipulate. … They can be moved by statistics if statistics are put into a story.

I've been very impressed with what a big sort of meme this is in business right now. I've been contacted by researchers from Coke, from Nike, since the book came out, who are all trying to figure out how they can use storytelling better to achieve their goals — make more money.

Are yoo doing anything with them?

I have given a few interviews where they were sort of feeling me out and asking for ideas about things. Nike was actually working on a thing that was really cool. They do charitable work in Africa. It was really sort of laudable work. I worked for a little bit on that.

In the book you write, regarding storytelling, "We're the species that can't grow up." What do you mean by growing up?

In Peter Pan, the key moment of leaving childhood behind and growing up is when you leave Neverland for good. You never go back. But … we never leave it behind. In that sense we're very Peter Pannish. And we spend every bit as much time in Neverland as adults as we do as children; we just kind of change how we do it. Instead of making up our own stories, we just live inside other people's stories.

Exception to [passive consumption of stories] are kind of neat. You know there's LARP — live-action role-playing. It's got this incredibly dorky reputation — even D& D geeks get to make fun of Larpers! But to me, it's really cool, and I wonder about things like World of Warcraft, which is basically like LARP. It's LARP! But it's virtually. So we still make believe, in very childish ways, too.

Do you play video games?

I'm a fan of video games in the sense that I think they're really interesting. I don't actually play them any more. I stopped playing them because I got motion-sick from them. Otherwise I'd be a total video-game addict and I would have never written this book.

Regarding LARP — it's kind of on the cultural fringe, isn't it?

World of Warcraft is a dominant [multi-player online role-playing game]. But there's others. What I see happening is, right now, the dominant genre is sort of the fantasy genre, the dorks-and-orcs crowd. But there's no reason that this can't be Desperate Housewives. They're focusing on this little niche of people who are used to playing RPGs, the guys who graduated from reading J.R.R. Tolkien and D&D, and who graduated to playing World of Warcraft. But there's no reason my wife couldn't be playing Gray's Anatomy-style role-playing games in the digital universe.

If I had bets to lay, that's where I would see story going, and going in really interesting directions in the digital world. Worlds of interactive fiction — worlds that are very much like returning to Neverland in a childish sense, where most of the draw is the draw of collaborative storytelling, and interactive storytelling.

But unlike most RPGs, the world of a Gray's Anatomy is basically realistic.

But a lot of them are realistic — maybe secret-agent games that are highly realistic. Iraq-war games, commando games.

But those depict a heightened sort of reality. Gray's Anatomy takes place in a slightly glamorized version of the everyday world. If you're role-playing, do you want to be The Incredible Hulk or a doctor in a hospital?

My wife does not want to be The Incredible Hulk. You and I do. But my wife does not want to play Incredible Hulk. She might want to play the hot doctor courting McSteamy or whatever his name is, on Gray's Anatomy.

My guess is that video-game marketing … they're not going to be happy with this narrow segment of market share. They make a ton of money, and they're making it off of mainly young men. My guess is that they're gonna broaden out and go after my wife. And they're not really going after my daughters at this point, either.

There are a few games designed for young girls.

And we have some of them. and they like them. [It's] amazing to me that they like them, I can't imagine how anybody would like games about running your own bakery!

World of Warcraft, James Bond-style games, Star Wars-style games — these are all very action-oriented, action-movie-style fantasy worlds. But I don't see any reason in principle why other sorts of fantasy realities wouldn't be appealing. If you love romance novels in the real world, I don't see why you wouldn't love to participate in one in the virtual world.

In the book, uou cite studies showing that reading fiction can increase people's empathy. What about in the interactive realm?

I don't know of any research that's been done on the digital games. My guess is that you wouldn't find much effect yet. And it's partly because the games have not reached their full potential yet. Many of them are more towards the action spectrum — there's not a lot of perspective taking where you have to put yourself into anotherr [character's] frame of mind [as you would in fiction].

This is all exciting to me, because we don't know the answers. We don't know how our time in digital universes is going to shape us. We're just starting to understand and starting to examine in a rigorous way how stories in book form or film form change us or influence us.

What about violence? In many video games, the point is killing. Doesn't that affect the player?

The video-game violence thing, the same as the media-violence thing — we were very very concerned with the rise of TV, 50, or 60 years ago, that TV was going to turn all of our kids into psychopaths. [But] psychology has never been able to answer the question ... about whether or not there is a causal relationship.

I'm certainly concerned about what you're talking about though. We have a little kid who lives next store, he's about 8, 9 years old. And he talks about playing Call of Duty. And I don't say this, but I'm like, "Why are you playing Call of Duty?" And he talks to me in great detail about what he does. "Yeah, I slit this guy's throat, and I snuck up behind him, and I stabbed him." … This incredible brutality, you know? And he's not aware of that. … It's just a game to him. But you do worry about what the effects are going to be.

You talk about how simulators such as military pilots use, and even dreams, can create the same physiological and emotional responses as events in real life. Why not in video games?

It makes perfect sense to me. That's what I expected to find when I got into the research. But the research was just not definitive. The research about media violence in general is really a mess. You'll have some people saying strongly, "OK, we've got enough research, we've done this big meta-analysis, we can conclude that it does cause a rise in real-world agresssion." And then you find other people who are just as distinguished, and have just as much in publication, and they've been working in the same area for just as long, and they say, "No, it doesn't work that way."

But a lot of people have exactly the same intuition you do — that the immediacy of it, the idea that you're not watching it from the outside, you're the avatar, you are inhabiting that. You don't say, of the game, "He killed her." You say, "I killed her." It's you.

But you argue in your book that there's a crucial difference.

The one thing that does give me some hope in that category — this is something that's often left out of the media-violence discussion — is the violence is almost always socially acceptable violence. Whether you think any violence is good or bad is [another] question. But Grand Theft Auto is really a grand blazing exception to the rule, where[as] for the most part the games do send the message that your job is to inflict heroic and righteous violence. You are to protect the good and weak against the bad and the strong.

And that's the message of media violence in general. The bad guy kills, and he kills in an unjustified way, out of greed, evil, whatever. The good guy kills the bad guy to protect the innocent and the weak. So there is a sort of morality in the violence, even if it's also troubling.

Meanwhile, many Native American tales, for instance, are sort of morally ambiguous.

One thing that made me wonder about it was sort of trickster tales.

The coyote.

I remember reading these incredible Yanomamo Indian folk tales, which are just an incredibly isolated people. One of their great hero tricksters is this guy with an 11-foot penis who can impregnate girls around corners. And he's kind of a bad guy. But he's actually sort of a culture hero, makes people laugh.

Most of the trickster heros, they're usually bringing somebody down in authority, somebody who's arrogant, somebody who's swaggering around. The guy with the 11-foot penis —

There's an RPG for you, by the way.

— he's kind of little and dwarfish, and no one will give him any respect, but he's always stealing these women out from beneath their swaggering husbands' noses. I think the message of the stories is a very ancient message about not being haughty, not being arrogant, not lording it over the weak, those sorts of things.

One of the overarching concerns in your work is "consilience." What's that about?

Consilience is the marriage of the disciplines. It's an argument based on E.O. Wilson's book from 1998 that the idea of disciplinary barriers is a figment of our imagination, and there's nothing to keep people from the humanities from wandering into the sciences — borrowing methods, borrowing ideas — and there's nothing to keep people in the sciences from migratnig into the humanities and asking big questions about why do we have art, and how does art affect us?

The idea is really counter to our intuitions. But I think at least for me, it's really obvious once you think about it. And the idea's basically just this: that we think about art as being in the sort of province of the humanities. But it's not. That's a one-sided way of looking at it. We think of art as the cultural product par excellence. But art is also deeply natural. You can't go anywhere on the planet and not find art, no matter what kind of society you go to. Literally a human universal. And with fiction, you always find the same kind of fiction. You don't ever find a society where you lack problem structure, for instance. You don't have the kind of society where they write stories mainly about like making the morning meal. It's always about the big plights of human existence. And you don't ever find a society where children do not play at story by nature. As naturally as learning how to work, they learn how to pretend at stories.

We've drawn a line between science and the humanities, between art and culture, art and nature, that has really retarded our understanding of these things. For instance, a scientist does not see fiction as his jurisdiction. So they don't ask big questions about it. And other people might ask big questions about story, but they're unequipped to answer them because they don't have the methodological, statistical sort of [tools]. It sort of requires a marriage betweeen the disciplines to try to answer these questions.

Does consilience figure in your teaching career?

I mainly teach freshman composition. … My professional situation is somewhat famous. I'm sort of famously underemployed. A real disconnect between the level of success of the books I've written — I've had a lot of media attention, Science and Nature and The New York Times Magazine — and my sort of dismal professional [record].

I've had really hard time getting a job, and part of the problem is I just fall in the cracks. I'm a little bit of a mutant as far as my discipline. I don't fit nicely into any of the disciplinary pigeonholes. And a lot of it's like in my home field, there's a lot of wariness about me and what I represent, and the worry that … allowing science in the humanities is like allowing something unclean into the temple. Or a snake into the garden. I think it's amisplaced worry, but it's made it hard for me to find real full-time, tenure-track academic work actually in my area.

Even though as you point out, when the snake comes into the garden is when things get interesting.

That's what I think! I think they'd be much better off with me in the garden.

What you have in literary studies, my home field, is a field that badly needs a shake-up. It badly needs fresh ideas, it badly needs some controversies. It badly needs a new hardball argument. And it badly needs to change how business is done. Because right now, that field is sort of gradually fading away. All of the indicators are terrible.

On the other hand, you don't have a big teaching load.

An enormous upside. In some ways, the luckiest thing that ever happened to me was not getting a job. It was a very fortunate kind of failure. The kind of job I was likely to get would have had massive teaching loads, and tons of service. Not a job where I would have time to do the research and writing that I've done. I still would like to have an academic job, because I like that world, too.