At a recent Hollywood fundraiser, the out gay actor Neil Patrick Harris introduced President Obama by saying that he would be "coming out soon!" The joke is a clear indication of a seismic cultural and political shift. While Obama has openly courted the LGBT community by declaring his support of same-sex marriage, it was not that long ago that the political indifference of the Reagan era to the HIV/AIDS epidemic galvanized the gay-rights movement. In 1987, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was formed as a direct-action grassroots network. Its unofficial propaganda arm was called Gran Fury, a collective made up of activists and artists.

Donald Moffett was a founding member of Gran Fury, but just prior to his involvement, he created street posters that became an iconic image of the era. One side shows an amused Ronald Reagan above the words "He Kills Me" in bold orange letters; the other shows an off-center bright-orange target.

Covering one wall at the entrance to the exhibition Donald Moffett: The Extravagant Vein, at The Andy Warhol Museum, the posters demonstrate Moffett's visual dexterity. While best viewed as street art, the posters here form a backdrop for "Lost Weekend" from 1997, a piece from Moffett's "Blue (NY)" series. The pairing serves to encapsulate a decade in which the artist began by focusing on more militant work and ended with what organizing curator Valerie Cassel Oliver calls a "tentative sense of optimism."

On the other side of the exhibition entrance is "Untitled (Lot 010804)," a more recent piece. While technically a painting, it is also sculptural. Here Moffett tests the limits of the wall by displaying the painting as if it were a signpost anchored in a bucket of concrete. The surface of the painting also defies two-dimensionality. Instead of lying flat, the paint protrudes into space. By framing this survey exhibition with these particular works, the viewer is introduced to the artist's interest in challenging perceptions, whether visual, literal, political or philosophical.

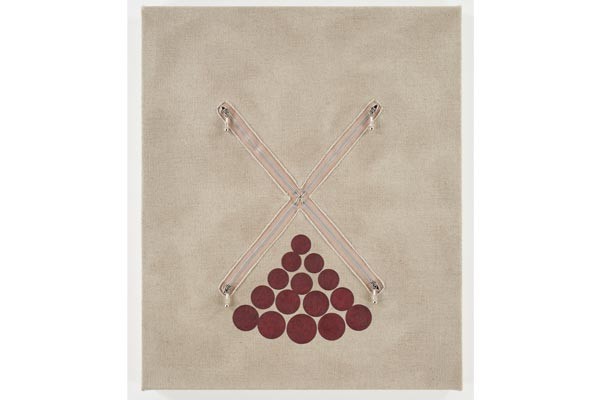

On their surfaces, literally, Moffett's paintings are about painting — the act of painting, the materials of painting and the history of painting. But they are far more complex than that. They are also about identity and about the boundaries and definitions of art as inextricably bound up in the social, political and historical contexts in which it is made. Like many of his art-historical antecedents, Moffett experiments with materials and colors in an effort to destabilize the surface of the painting. He incorporates zippers and neatly sewn holes into his "Fleisch" series and he literally flays open the painting surfaces of his "Gutted" series, unzipping them to reveal monochrome studies underneath. Monochrome is also something that Moffett explores in "Comfort Hole," in which he extrudes white paint so that it appears as if it is growing like fur from its support.

Paint is not the only medium Moffett uses to confound his surfaces and thereby viewers' perceptions. He also uses light. His "Blue (NY)" series is made up of photographs of the blue sky that at first seem to be studies in monochrome — art-historical descendents of Yves Klein, Picasso and the Byzantines. They are ethereal and spiritual, yet in making them Moffett was keenly aware that sky blue is a trick of perception caused by an optical phenomenon. And so with all things Moffett, there are endless layers of complexity. But it was the color red that led Moffett to layer video projections onto his painting surfaces. In "What Barbara Jordan Wore," the congresswoman's red dress at Richard Nixon's impeachment becomes both a visual and philosophical focal point. Moffett projects images of the hearing onto gold painted surfaces, which causes them to shimmer, flicker and float somewhere between figuration and abstraction. He uses a similar effect for his "Extravagant Vein" series and for his "D.C." series, although the latter uses densely layered silver paint.

Underlying all of Moffett's work is the politics of identity and the way political power dictates our lives. While Moffett himself makes a distinction between his more activist work prior to 1993 and his work after 1996, Bill Arning argues in his catalogue essay that any interpretation of Moffett's career as "bifurcated" is "overly simplistic." This survey includes very little work made prior to 1997; the inclusion of more early work, including Moffett's commercial and activist projects produced by his design firm Bureau, would have been a welcome addition. Nonetheless, the exhibition demonstrates Moffett's unique vision and his ability to critique the world, influence political change and expand the art-historical conversation.