Some artists are like creative athletes who approach visual problems like laboratory scientists. Examination, experimentation and the imperative execution — all of which likely require a high physical and mental pain threshold. Reject, reformulate. Repeat.

RR&P: Repetition, Rhythm, and Pattern, an exhibition at SPACE gallery, showcases the work of 12 such artists, a group of emerging and mid-career talent from our region and throughout the U.S. Curated by internationally exhibited artist/curator Lindsey Landfried, this touring show surveys trends in installation art, drawing, sculpture and video with post-minimalist prescriptions past and present. Design-driven, resourceful and clever: It’s minimalism, but with just enough humanity.

Thematically, repetition, rhythm and pattern is broad and well-trodden territory in art history. For this show to bring something fresh and notable would be most ambitious.

A reductive form repeated is seen in Landfried’s own tiny doodle loops (a la Cy Twombly but miniaturized) in "Tyrian and NonSpectral Color"; they’re marks so fallibly human, a work session’s beginning to end is visible. Likewise, "Illumination + Snack" is Kate McGraw‘s belabored, simple-made-complex patterns in bright inks. But visual experimentation always has a problem to solve. Landfried’s wall-sized million loops on paper are afflicted with catastrophic but exacting dents, while McGraw’s scale of dedication is expressed in an approximately 30-foot roll of paper (its ends rolled up like a giant scroll). Both works are drawing experiments with generous interruptions into the third axis, emanating human-scale energy.

Two totemic works by Corey Escoto and Megan Cotts echo a conceptual similarity. Escoto’s cleverly titled "Diamond Dhallus and Ionic Dongle" uses curated junk — think spent paint-roller naps and couch foam — to create classical columns, while their "marble" finish is either faux-painted or nonchalantly printed photograph. The mishmashy directness suggests an Art Brut modesty, only this is sly ingenuity that floats on an island of plastic the size of Texas where nothing can be created, only assembled. In "Helen, I Love You," Cotts uses handmade paper honeycomb to create a 70-inch-tall floor-standing object in bright orange. The vague shape, best described as a pawn chess piece, is somewhat lost on me — personal, historical or purely aesthetic? Still, it’s eccentric, with its passé decorative largeness. Both Escoto and Cotts summon human foibles against the constructed object, whether it’s classical, reified or factory-made.

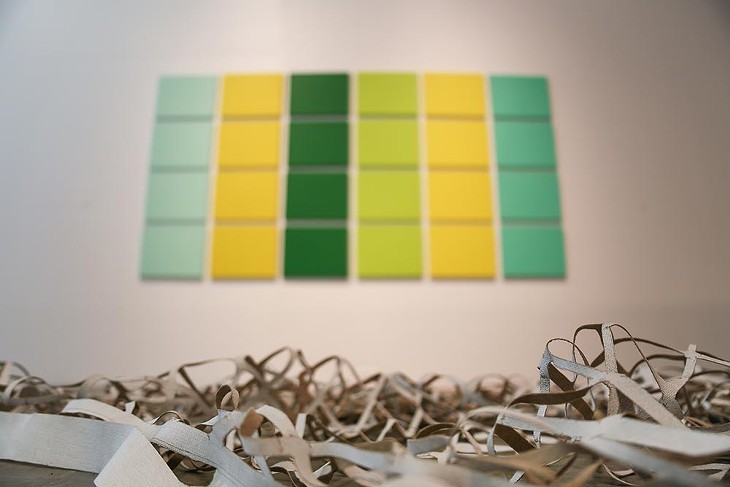

Similarly, Kim Beck’s construction-zone fencing facsimiles, hand-cut from oil-primed linen, are like a wrist-punishing meditation on our too-far-gone state of industrialization. One swath is piled on the floor, another tacked loosely to the wall and draped toward the ground like empty skins. Their flaccidity communicates a feeble unhappiness that is almost comical.

Helen O’Leary works in the disappearing territory of the sculptural rectangle. "The thing about yellow" and "Geometry of White (armour)," equal parts painting and sculpture, harken to early post-minimalism (Eva Hesse comes to mind) that features the lovable imprecision of human touch. The milky, over-worked layers of solid color belie the chaotic wood and glue substrate, a functioning disorder forced below a hardened surface.

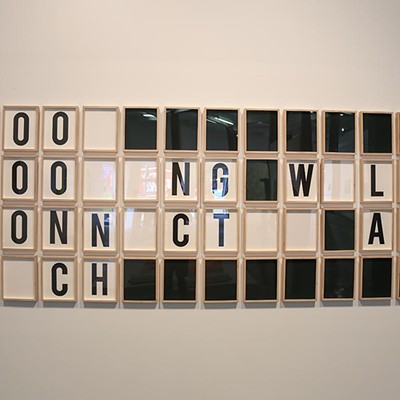

Persistence of light, planes and human perception play into Alex Paik’s wall-sized installation in paper, "Modular Wall Installation: Hexagon (Cube)." The individually mounted forms reveal the outlines of dozens of cubes whose neon colors pop when viewed from the proper angle and then all but disappear at another. Crystal Gregory’s leaded glass structures, "Before She Knew She Was There Where She Had Gone To She Was Really Away," also tend to reform at different angles, their negative spaces creating new views. Though different in media, both works establish rapport with viewers through a shifting geometry and negative space.

RR&P also includes work by David Prince, Brian Giniewski, Lilly Zuckerman and Anna Mikolay.

Many individual works in the show are handsome, generous and easily appreciated through a rich, decades-long art history. Unfortunately, something different happens when the exhibit is taken in as a whole. SPACE is overstuffed, with a whopping 27 works of mostly large scale that, in the genre of post-minimalism, is the sort that thrives in open white spaces.

Consequently, the sum is too distracting and the parts, though presented as rarefied, get lost in the visual competition. Also, the staunch design-driven attractiveness in many of the works boils down to a frustratingly effortless art experience — though this is coming, admittedly, from a viewer who'd rather be provoked than pleased.

Perhaps it’s just a hunch, but this exhibition may reveal deeper struggles artists face in the art world’s current supply-and-demand nightmare. With few resources available, creative athleticism and laboratory-like deductive thinking might be taxed by the need to sell work. Talent and creds notwithstanding, perhaps risking a reinvention of the wheel can wait till tomorrow.