We are now so accustomed to the rhetoric of Pittsburgh's superiority that we have lost touch with the days when its ills seemed grave and its needs for improvement, acute. Why did we get Mellon Square? Because our post-World War II city was so notoriously smoky and dismal that Richard King Mellon could not get capable executives to agree to move here. "And if they did, their wives balked." So explains author Susan Rademacher in Mellon Square: Discovering a Modern Masterpiece, the second in the Modern Landscapes series from Princeton Architectural Press.

The Downtown plaza earns early entry in a prominent national series now, but a modern landscape was barely conceivable in the Golden Triangle in 1946. Other parts of town had old-time parks and the occasional square. But the city had built no new public space for decades, and Downtown had no designed open space at all. Meanwhile, the Pittsburgh Regional Planning Association declared in a report "that the automobile had become the dominant form of transportation in the Central Business District by 1937." The ensuing congestion was leading to the failure of small businesses, rising office vacancy rates and a precipitous decline in property values. Garages were needed, as well as open spaces.

Richard Beatty Mellon and his cousin Paul sensed an opportunity for both the city and their own business interests. They hired architects Mitchell & Ritchey to collaborate with landscape architects Simonds & Simonds to plan a complex centered on the block bounded by Sixth and Oliver avenues, Smithfield Street and William Penn Way. The site, which the Planning Association had recommended for such use, would include an underground parking garage, with office towers for Alcoa and U.S. Steel/Mellon Bank facing each other across an open space. That initial concept was the beginning of Mellon Square as we know it today. The two flanking skyscrapers that we see now proceeded only when the plaza/parking garage hybrid got the go-ahead.

The book centers upon a detailed recounting of the design and construction of Mellon Square. The underground parking garage was a new idea, and the modern plaza on top of one was truly unprecedented. Certain early design proposals, such as a round fountain and built-in restaurant, fell by the wayside. And most elements took definitive shape only after numerous iterative refinements. But the final design emerges through a series of drawings as if it were inevitable.

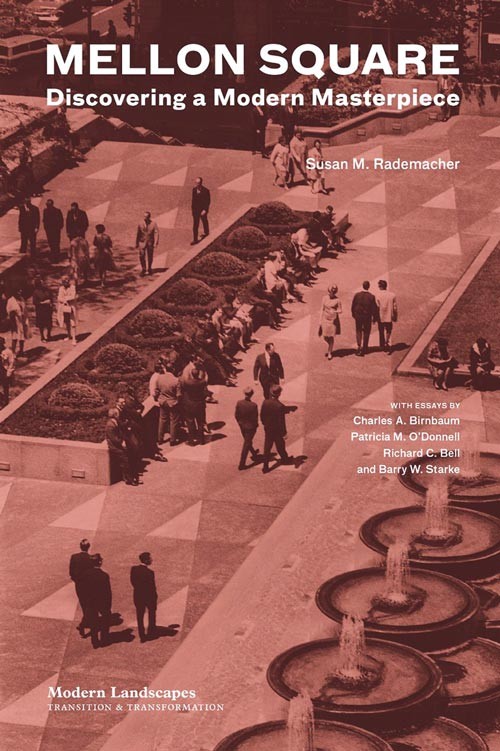

The broader plan accommodates cars at the sides and beckons pedestrians at the corners. It reconciles the slope of the streets by treating the spaces as overlooks above the street in most places, with the iconic cascading fountains along the steps to the corner of Smithfield and Oliver. The planters at the plaza level, through shrewd articulation of shape, height and plant material, allow for the suitable location of paths, spaces and seats with multivalent and asymmetrical grace, punctuated by that iconic paving pattern in layered triangles. Of course, these elements have undergone some significant changes over the decades, culminating in the recent, deservedly lauded renovation by the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy. But author Rademacher (who is also the Conservancy's parks curator) accounts for those changes in detail as well.

Throughout this narrative, collaborators Mitchell & Ritchey Architects and business partner and brother Philip Simonds play key roles in this project, but landscape architect John Simonds emerges as a particular hero. The Harvard-educated designer drew influence from the modernist icon Walter Gropius as well as the lesser-known, more gentle Harvard dean Joseph Hudnut. "One designs not places, or spaces, or things," Simonds wrote. "One designs experiences." His 1961 book Landscape Architecture remains an influential text in the discipline today. And his career of major projects in Pittsburgh and nationally put him at the top of his profession, a stature that book series editor and essayist Charles Birnbaum seeks to bolster.

The paradox of Mellon Square is that it inaugurates the era of Renaissance I, a period of Pittsburgh history when automobile- and plaza-driven megaprojects in the city have a checkered legacy at best. Point State Park is still celebrated, and Gateway Center is admired, but redevelopments in the Lower Hill (in which Simonds and Simonds contributed landscape designs, albeit incomplete ones) and East Liberty are widely viewed as historically disastrous.

This is not to question Simonds' talents or legacy, only to wish for broader discussions of 20th-century landscape and urban design in Pittsburgh and further afield. That is a larger scope than a book of this size can reasonably cover, but stimulating interest in the issues can be counted as one of its virtues.