The foremost problem with the current mortgage crisis is, of course, that too many families are losing their homes or risking doing so. Among important secondary issues, though, is that when foreclosed homes sit empty, they decay physically, declining in value and pulling the value of other nearby properties down with them.

Clearly, no one wants that to happen. Unless they are Wal-Mart. No, the mega-retailer isn't in the housing business, at least not yet. But with more than 7,000 stores worldwide, it is certainly in the real-estate business. In certain circumstances, Wal-Mart is not only happy to let defunct stores sit empty; frequently, the company actually insists on it contractually.

This and other revelations about the afterlives of closed big-box retailers are the subject of Your Town, Inc., a new exhibition of work by artist Julia Christensen, based on her forthcoming book Big Box Reuse. The exhibition runs through Nov. 22 at the Miller Gallery, at Carnegie Mellon (where I am an adjunct faculty member).

An artist by training and practice, Christensen became fascinated with big-box stores when she observed the sequences of structures and transactions that unfolded in her hometown of Bardstown, Ky. Wal-Mart built its first structure in the early 1980s, expectedly, at the edge of the town, drawing business and vehicle traffic away from the town center and its historic courthouse. That store soon closed, but not for lack of business. "[B]ig-box retailers are being vacated because the retailers are expanding to larger structures, usually within a mile of the original structure," Christensen explains. Indeed, a larger store followed at a nearby highway intersection.

Even more surprisingly, Nelson County (of which Bardstown is the county seat) elected to move its courthouse operations to the site of the old Wal-Mart. "The infrastructure for the traffic was there ... and the [other] empty stores surrounding the store offered the potential for economic development," explains economic-development officer Kim Huston in a quote Christensen cites. The Bardstown story is not tragic, in part because the town kept its historic courthouse building. But the story underscores the power of big-box retailers to siphon the life from the center of town, and then leave with callous abruptness when a better opportunity arrives.

Christensen's book and the several dozen photos of the exhibition present case studies of huge suburban retail structures and the eccentric, unexpected uses to which communities put them when the original owners depart. She documents senior-citizens centers, an indoor racetrack, charter schools and that perennial favorite, the Spam Museum. Yet this variety derives precisely from the common practices of restrictive leases and deeds that forbid competing retailers to occupy the buildings or sites for periods of 50 or 100 years. Happily enough, many varieties of reuse are possible.

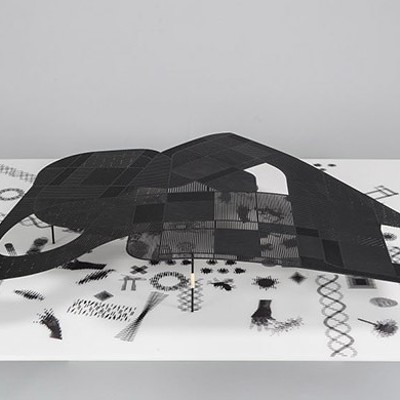

Christensen is an analyst rather than a bomb-thrower in her book, so the arguments are measured. The Miller Gallery installation, though, is more critical. Stripes for a code-correct parking lot are painted on the gallery's floor. Only six parking spaces fit in a room with a capacity of 250 people. Aside from the photos, the primary artifact in this space is the Unbox, a sequence of folding frames and screens.

The Unbox, says curator Astria Suparak, was "informed by all of [Christensen's] research, [but built to be] the opposite of a big-box structure in every way." Christensen and some of her students made it by hand in Oberlin, Ohio, where she teaches, to be modular and transportable. All of the components, down to the nails, were bought from local, non-chain outlets. The vehicle that brought it to Pittsburgh ran on biodiesel. The Unbox is adaptable, and it will change its shape and degree of enclosure through a full schedule of receptions, lectures, discussions and other events, key components of this show. (See millergallery.cfa.cmu.edu.)

The meaning of the Unbox as an armature of specific community will unfold literally and figuratively in its continuing use. But the non-plastic, non-disposable characteristics of its materials are immediately apparent. And while Christensen's book underscores the ingenuity of the communities that have reused big-box structures, her exhibit emphasizes the possibility and necessity of not building them in the first place.