Sonny Jani always maintained he would stay in McKees Rocks until his mother died.

The 1988 Sto-Rox graduate moved to the suburbs as soon as he could, after amassing a small property empire and eventually winning a landmark lawsuit against the NFL on behalf of Mike Webster. But until a few months ago, he continued to work out of a small office at the back of Blue Eagle, his family’s Broadway Avenue convenience store.

Six days a week, after tending to business, Jani would sit down to eat with his mother in the flat above where she lived before driving back home to Cranberry Township.

When Kamlaben Jani became sick in the spring at age 85, Sonny and his siblings knew they had some tough decisions to make. They settled on selling the store, as long as they could agree on an owner to entrust with their parents’ legacy.

Seven years earlier, a Muslim family from Pakistan who bought a rival store two doors door, would have seemed like unlikely candidates. But a slow blossoming friendship led to a transaction which, they now say, came to represent much more given their distinctive family histories.

“For the longest time I was raised up to hate Muslims,” Jani says, noting his sister was once held captive for 48 hours by a neighboring Muslim family while the Janis still lived in India.

Hindu-Muslim animosity in the Indian subcontinent extends back centuries, and has recently reasserted itself there at the center of political life through the rise of Prime Minister’s Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party. But for many families connected to either side, the feuding is fused with personal history.

Anytime Market owner Mohsen Khan says his upbringing was rare in the sense that his father had some Hindu friends who would occasionally come over to watch cricket. But the Khans, who have lived around Pittsburgh since the 1990s, haven’t been spared from the sectarian trauma. Mohsen’s grandmother was forcibly uprooted from her home and marched to the newly formed nation of Pakistan during the Indian partition.

“She was actually forced to leave India in 1947,” Khan tells City Paper. “One day, her dad was like, ‘Alright, we gotta go.’ And she had to travel like 200 miles to Lahore, and she was probably only like 8 or 9 years old.”

Although leaders like Mahatma Gandhi had fought for a unified independent India, the separatist faction eventually won out and the Indian subcontinent was split into two nations at the time of its emancipation from British rule. The larger portion, today’s India, was apportioned for the Hindu majority, while Pakistan and West Pakistan (now Bangladesh) were formed for the Muslim minority. It’s estimated up to a million people died crossing the borders following the partitioning.

“Could you imagine hundreds of millions of people all at the same time were told, ‘leave your home and go somewhere else?’” Khan says.

When Jani arrived in the U.S. at age 15, he felt he had more to fear from white American teenagers than the small number of Pakistani Muslims who then lived around Pittsburgh.

His business success meant some of those former bullies later called on him for help, and he would usually find them a job or an apartment when he could. Yet he continued to keep Pakistanis (he has had long friendships with Muslims from other parts of the world) at arms length for several decades.

Somehow, though, as rival business owners, Jani and Khan came to be close friends — drawn together by a similarly mischievous sense of humor. The prank that secured their friendship was supplied by a handful of difficult customers known to both store owners, who took turns sending them next door, promising the other proprietor had what they were looking for.

“You know people get real hurt, and they don’t know how to take a joke,” Khan says. “When I hear a joke from Sonny, I just give him one back straight away…So over the course of the years, I mean, I got to know his family, too. I got to know his mom, his sisters, his brother, his brother in law.”

But when it comes to the fate of a 40-year family legacy, as was the Blue Eagle to the Janis, intergenerational conflict can quickly reassert itself.

Kamlaben traveled 7,000 miles from Gujarat, India to build a better life, and Blue Eagle came to represent the security and permanence her family had made for themselves in America. For nearly forty years she worked there seven days a week, Jani says, without ever closing for major holidays like Thanksgiving or Christmas.

For Jani and his siblings, their bond with the family business was also strong.

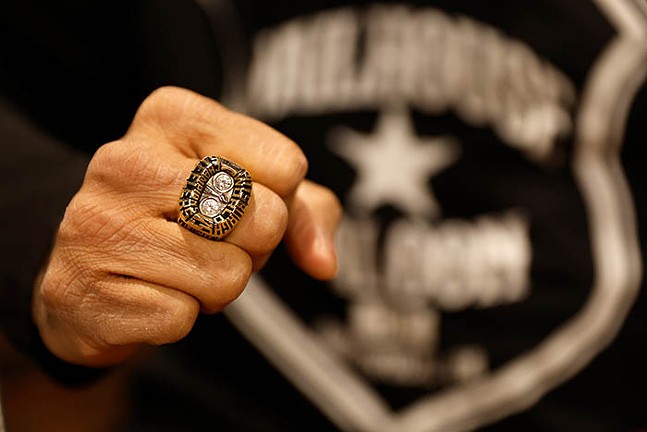

“Blue Eagle was not just a corner store to me because I raised my two kids there, Mike Webster was there. When I got kicked out of my house, I was living there,” he says.

Jani was 22 and running a sports card store when he ran across a down-and-out Mike Webster sleeping in a Downtown bus shelter. But where others may have dismissed the brain-damaged former Steelers star, Jani found a way to improve both their fortunes by setting him up on a signing and speaking circuit, and splitting the profits. Jani eventually became a close friend and caregiver to Webster, and, after he died, he successfully sued the NFL on behalf of his estate.

Khan says he discussed his interest in Blue Eagle before Kamlaben became ill, asking simply if he could make the first offer. Jani agreed, but he didn’t immediately have his whole family’s backing.

“I think it was harder for people in his family to accept it,” Khan says. “Just because they're older and they've been through stuff in India.”

Kamlaben, who Jani says, came to like Khan despite her lifelong dislike of Pakistanis, helped settle the matter with her vote of support.

She said, according to Jani, “I want you and your brother to live happily, and if this would make you happy, then do it.”

When Kamlaben died in August, Khan was among the small circle of friends and family invited to her Hindu memorial ceremony. They closed the deal on the store several weeks later.

“We’re not in a war, we’re in a friendship,” says Jani. “And now our friendship is growing.”