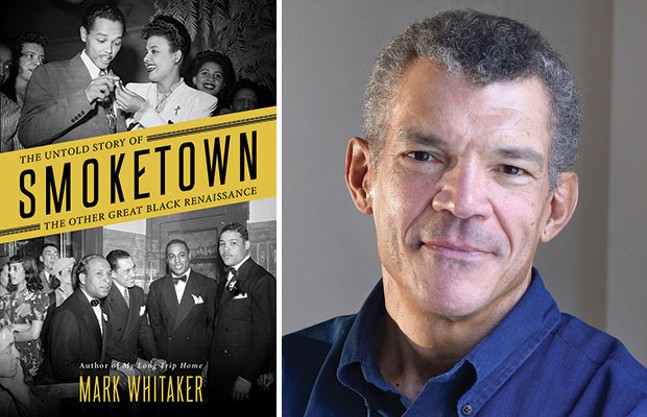

Local culture vultures know Teenie Harris’ photography from the Carnegie and may have an Erroll Garner LP lurking in their stacks of vinyl. Baseball fans probably know how Cum Posey transformed the Homestead Grays from just another sandlot team into the greatest in the Negro Leagues. But journalist Mark Whitaker is the first to consider the prolific incubator of Pittsburgh’s black community as a whole in his new book, Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance (2018, Simon & Schuster). Whitaker will talk about his book at Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures series, on Wed., Feb. 21.

Whitaker, a veteran journalist who has worked for CNN Worldwide, NBC, Meet the Press and Newsweek, among others, was at work on his 2011 memoir, My Long Trip Home, when he started really digging into the story of Pittsburgh’s black community. Whitaker’s father grew up in Homewood, and he made frequent visits to see his paternal grandparents. His grandfather was one of the first black undertakers in the city, the owner of the Whitaker Funeral Home, a long-time fixture in Homewood. His grandmother ran the Edith Whitaker Funeral home, which operated for many years on Fullerton Street in the Hill, before she moved the business to Beltzhoover. His family research opened the city up to him: There were so many African-American innovators and creators.

The brilliance and vision of publisher Robert L. Vann; the largesse of numbers kingpin and Pittsburgh Crawfords owner, Gus Greenlee; the talents of baseball great Josh Gibson, singer Billy Eckstine, photographer Teenie Harris and playwright August Wilson. Then, there were the pianists Billy Strayhorn, Erroll Garner, Earl Hines, and Mary Lou Williams; if New Orleans jazz is captained by a trumpet, Pittsburgh jazz is led by a piano. Whitaker was pulling at all of these individual threads when he started to see them as part of a complete tapestry. The interconnectivity of Pittsburgh’s black community then came into focus.

The Harlem Renaissance, in the 1920s, was very much the culmination of “the life of the mind,” as Whitaker phrased it, urbane and sophisticated. Whereas the black renaissance in Pittsburgh suited the city itself: Born of commerce and business, it was brawny, corporeal and expressive.

Early on in Smoketown, Whitaker lays the groundwork for black Pittsburgh’s awakening: “As likely as not to have been descendants of house slaves or ‘free men of color,’ these migrants arrived with high degrees of literacy, musical fluency, and religious discipline. … [O]nce they settled in Pittsburgh, they had educational opportunities that were rare for blacks of the era, thanks to abolitionist-sponsored university scholarships and integrated public high schools with lavish Gilded Age funding. Whether or not they succeeded in finding jobs in Pittsburgh’s steel mills (and often they did not), they inhaled a spirit of commerce that hung, quite literally, in the dark sulfurous air.”

Whitaker is a lifelong jazz fan, and his love of the music shines through in his prose. But, as he told City Paper via telephone, one of the great joys of this book was that he could bring to life some lesser-known, but equally important leaders and creators.

One of those was Robert L. Vann, publisher of America’s premier black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier, from the paper’s inception in 1910 until his death in 1940. “Vann was a real visionary,” says Whitaker. “I think because he died so young, and because the Courier went into decline, there is just one academic book about him and that’s it. There are lots of characters in my book who have already been written about a lot, and I hope I do justice to them, but there are people like Vann — they are just as fascinating. When you look at his editorial strategy — from the very beginning realizing that the Courier had to be a voice for the black community. It started on a local level with editorials and the stories that he covered, but then he increasingly took that national. To realizing that he had to have great writers, great crusading reporting, but also writers who he would promote individually. So he put the names of all these people — Joel Rogers in Ethiopia, Chester Washington reports from the latest Joe Louis fight — he turned these reporters into celebrities.”

Smoketown closes with an elegiac chapter about August Wilson, which also covers the era of industrial decline and the economic deterioration that decimated neighborhoods like Beltzhoover, as well as ill-conceived (one could say malevolent) urban planning that killed the Hill. Those communities still haven’t recovered, and some are in worse shape than ever. Where Edith Whitaker’s funeral home once proudly stood, the entire block is deserted, according to Whitaker. “And the people stuck in these communities really got screwed. I think that to bring back those neighborhoods is going to require a specific combination of — a specific kind of attention. I don’t want to use the word ‘intervention,’ but it’s almost like that, and I think that it has to be multi-pronged.”