Pittsburgh is changing. From revitalized business districts and construction of luxury apartments to the disappearance of some long-loved establishments, Pittsburghers have different destinations now. And the way they are getting to those new destinations is changing, too.

By looking at U.S. Census data, Pittsburgh City Paper analyzed the changing commuter patterns of Pittsburghers. From 2010-2016, residents of the city, Allegheny County and the region as a whole have adjusted the way they get to work. All three areas saw an increase in the number of workers, but the city of Pittsburgh saw the largest gain, a 4.3 percent jump.

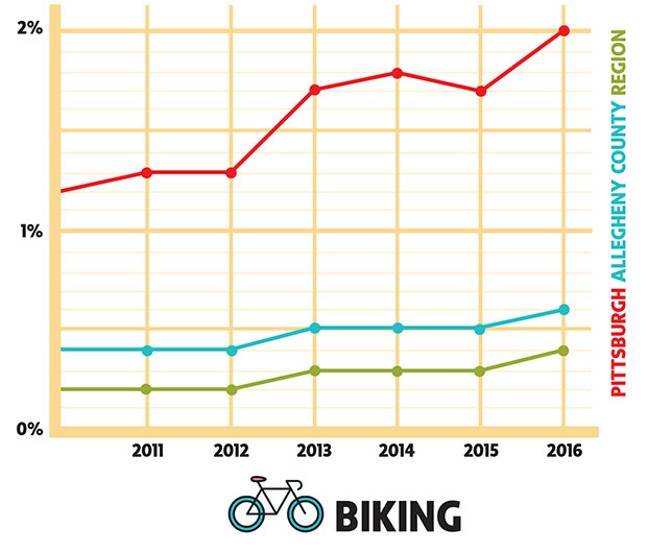

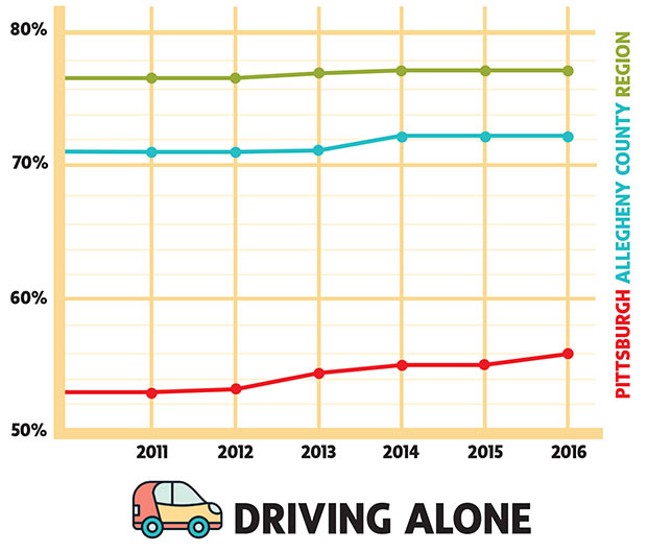

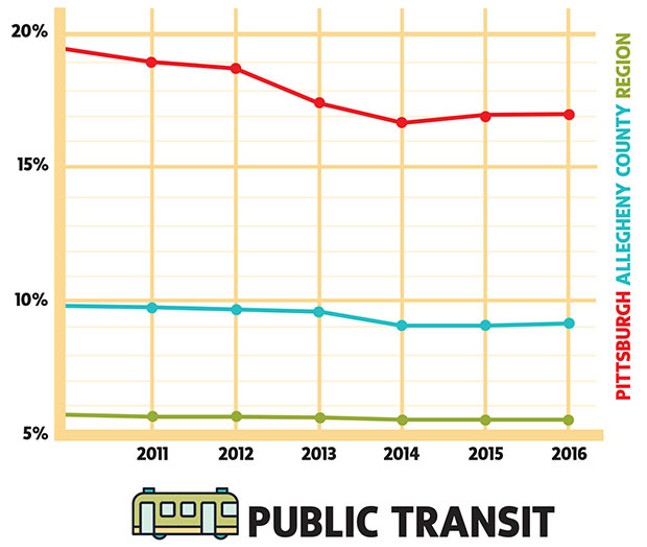

More people are biking to work, even as more people are commuting alone in cars. Overall, fewer people are using public transit. Still, some things remained the same. About 11 percent of Pittsburgh workers still commute by foot; this is among the highest percentage of pedestrian commuters in the country.

Karina Ricks, director of Pittsburgh’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure, is encouraged by those biking and walking numbers, as they can help reduce traffic. But she believes the city can do more to help people get out of their cars.

“We need to make a big push to make it really easy ... for people to use these alternative modes,” says Ricks. “At the same time, I think there are a lot of people using those [non-driving] modes a lot more. But we are capable of so much more.”

Bike commuting saw the sharpest increase of any commuting mode in the city. Overall, it’s still a very small percentage of commuters, but in six years it nearly doubled, to 2 percent. Ricks says the increase in bike infrastructure and protected bike lanes has encouraged more commuters to get on their bikes.

“I think one thing that is leading to an increase is actually having safe facilities,” says Ricks. “There is a lot of pent-up demand. People will bike if they feel it is safe for them to do so.”

The city of Pittsburgh had 1,704 bike commuters in 2010 and had 2,964 in 2016, an increase of 1,260 bike commuters. Ricks is proud to see more bike commuters considering the city’s winter climate and hilly topography, and she expects to see even more bikers in the future. “We fully anticipate that mode share will continue to tick up,” she says.

Despite the gains in bike commuting, and the continued presence of a large amount of pedestrian commuters, the city, county and region still saw an increase in commuters driving to work alone. The city of Pittsburgh’s number of drive-alone commuters rose 2.4 percent from 2010 to 2016.

In that time, Pittsburgh added 6,874 car commuters. In the region overall, driving alone remains the most popular mode of commuting, with 77.5 percent of residents participating, an increase of about .5 percent since 2010.

Ricks says the increase is likely tied to the improved economic standing of some Pittsburghers, since wealthier individuals typically choose the pricier option of driving over biking or public transit. “We don’t want to judge the people who have to commute,” says Ricks, who adds that some commuters might not have the option to avoid driving. “But, generically speaking, there’s a correspondence of more driving with people’s improved economic fortunes.”

Like most cities and regions across the country, Pittsburgh saw a decrease in commuters using bus or rail to get to work. Between 2010 and 2016, the region lost 2,605 transit commuters; the city lost 2,350. Ricks attributes these losses to two factors: better economic situations for more Pittsburgh residents and a lack of investment in public transit.

“The economic rise is definitely [a cause of transit losses],” says Ricks of commuters who can now afford to drive. “This is part of the reason we need to make investments in transit.” Ricks says investments to simplify and add frequency to transit service, like the proposed Bus Rapid Transit line from Oakland to Downtown, will help increase city transit commuting.

Even as Pittsburgh lost transit commuters, two suburbs in Allegheny County, Bellevue and Wilkinsburg, saw substantial gains of transit commuters, into the hundreds. Ricks says those suburbs saw public-transit growth because they have good transit service. Both Bellevue and Wilkinsburg are served by multiple bus lines with frequent service.