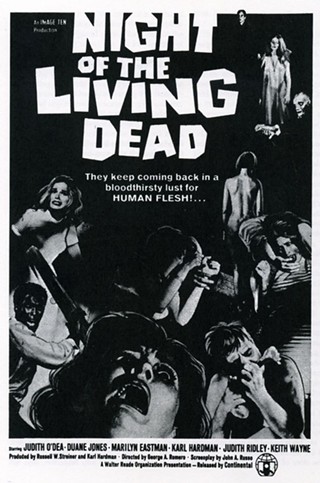

George Romero was known affectionately and colloquially as “The Godfather of the Zombie Movie,” thanks to a little black-and-white shocker he’d co-written, co-produced and directed in 1969 called, Night of the Living Dead. The 77-year-old filmmaker died July 16 after a brief battle with lung cancer.

The film was created in the hopes of making a modest financial return to fund more high-minded art films. George Romero, John A. Russo, Russell Streiner and seven other members of the “Latent Image” team created something that will outlive us all. A small group of panicked humans, trapped inside a dilapidated Pennsylvania farmhouse surrounded by a ravenous horde of reanimated corpses, each other’s instincts conflicting — sometimes violently — as they struggle to survive the night. It was intentionally evocative of Richard Matheson’s classic tale, I Am Legend, but it became so much more.

At first, the film was reviled by critics comparing it to base pornography, thanks to the unflinching sequences of cannibalism and violence. Because of its black-and-white presentation, the movie had a documentary feel: “you are here, this is now.” Audiences weren’t quite ready for its arrival. Not at first. But after a few weeks of playing in local theaters and drive-ins, Night of the Living Dead didn’t go away.

Part of the film’s legacy is borne on the shoulders of its lead, Duane Jones, an African American actor chosen to play the film’s hero, Ben, based on the strength of his audition and not because of the color of his skin. Yet, it proved to be a landmark creative decision during the height of the Civil Rights clashes occurring daily throughout the United States. Ben’s race is never addressed in the film, no slurs are used against him during the heated arguments. This in itself was groundbreaking: the black man was on equal footing with his white compatriots, because the world was ending around them. Race was secondary to survival.

The hungry ghouls devouring the living were retroactively compared to the creeping threat of Communism. Later, a conscious choice would be made to use the ghouls as parables for rampant consumerism (in the color follow-up Dawn of the Dead); in Day of the Dead, they were now the dominant race on the planet, with healthy living humans driven underground, hiding in bunkers and waiting for the inevitable. Day was filmed in 1985 and then, for a while, movie theaters were relatively zombie-free.

Between socially satirical tales of flesh-eating corpses, George Romero explored other themes of interest to him, all under the guise of lurid horror, the issues creeping up on you later. Take the poor, repressed titular character from Martin, played by John Amplas. A confused young man suffering from what may or may not be genuine vampirism, using a syringe and razor blades in replace of romanticized fangs and capes. Martin is as much a study of untreated schizophrenia as it is a vampire tale. The Crazies further explored themes brought up in Night and Dawn, only this time the threat comes first in the form of a virulent disease, and then later the government’s issue of martial law, embodied by the faceless men in white hazmat suits and gas masks exterminating crowds of people without remorse. “For the greater good,” to stop the disease. To abuse the power granted them by the panic of the nation. In times of crisis, Romero’s film argues, people willingly and gratefully suspend their own rights. Those in charge know this. Those in charge exploit this weakness of the herd.

Then there was Romero’s softer, more romantic side, no better envisioned than his unique Knightriders, about a troupe of pseudo-Renaissance actors who stage jousts on custom motorcycles, their leaders — Ed Harris in the King Arthur role, effects artist Tom Savini (who would direct the first and best remake of Night of the Living Dead with Romero’s blessing, creating a film both unique and evocative of the original) as his opposite, Morgan — at odds, but with mutual love and respect. The film’s long dénouement involves Harris making peace with all the portents of his death, and one of his final acts is to crown Morgan the “king” of the troupe. Savini’s grateful, loving tears makes the scene one of the most moving, and in less-confident hands, Knightriders could have been nothing more than a silly biker-sploitation flick, a drive-in also-ran. Instead, it stands alongside John Boorman’s Excalibur in theme and emotion if not pageantry.

Perhaps Romero’s finest work came as a collaboration with the world’s most successful horror author, Stephen King. Though Romero directed a straight adaptation of King’s difficult The Dark Half, it was their friendship and mutual love of EC Comics that propelled Creepshow to the classic status it holds today. Lurid, colorful, vivid, shocking and scary and hilarious at times, Creepshow is all things for all horror fans, perfectly evoking the spirit and flavor of the classic anthology films like Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror, the effects and gruesomeness off the charts. The enthusiasm pours from the screen as each Creepshow unfolds. This particular bottled lightning was never recaptured, not in the two sequels that followed and not in the countless others that came after.

Sad to hear my favorite collaborator--and good old friend--George Romero has died. George, there will never be another like you.

— Stephen King (@StephenKing) July 16, 2017

Following the odd and inaccessible Bruiser in 2000, Romero’s output became sporadic. That film’s box office failure sent the typical signal to Hollywood that Romero’s brand of unique disquiet was no longer in fashion. As usual, the ill-considered dictum became law and the director found financing increasingly difficult to achieve. For years, he shopped and developed a ghost story entitled Black Mariah, as well as an expensive, apocalyptic new chapter in his Dead series, this time named after the story’s central character, a rolling battle tank nicknamed “Dead Reckoning,” and the ragtag team of mercenaries cleaning up pockets of zombie incursion. For a long time, it looked as if his bizarre horror rock-opera, The Diamond Dead, would come to life and relaunch a Rocky Horror-esque movement, but funding collapsed and the project died with it. Then in 2004, with an expensive remake of his seminal Dawn of the Dead in the pipeline with the big studios, he finally got the greenlight for Dead Reckoning, now retitled Land of the Dead.

For many, Land was either a return to form or a diluted and slick late entry into the series. Made with a fraction of the budget granted to Zack Snyder and his dizzying Dawn remake (his decision to make running zombies the center of a raging debate to this day), Land of the Dead was a “greatest hits” of the previous films, with the added additions of bigger stars — The Mentalist’s Simon Baker, counterculture hero Dennis Hopper, and Asia Argento, daughter of Romero’s Italian counterpart Dario (who reedited Dawn of the Dead as Zombie for Italian audiences in 1979). It wasn’t a great success financially, but it heralded Romero’s return to the cinema.

For Pittsburgh, Land was Romero’s coming home. Though filmed in Canada, Pittsburghers retained their proprietary attitude that Romero was one of them, a hometown boy made good. Because of George, Pittsburgh is the “Zombie Capital of the World,” attracting visitors from all over the globe eager to visit The Monroeville Mall, made famous in his Dawn; or the Evans City Cemetery figuring so prominently in Night. That these places no longer even resemble the locations in the film causes no concern. And to celebrate Pittsburgh’s Patron Saint of the Undead, his son, Cameron, a filmmaker himself, organized the biggest film premiere the city has ever seen. For the Land of the Dead premiere, one hot day in June saw the arrival of all those who held George in the highest esteem. Not just “regular” Pittsburghers, but huge talents in their own right: Quentin Tarantino, Robert Rodriguez, Simon Pegg, Edgar Wright (the pair behind the Romero love-letter, Shawn of the Dead), director and effects artist Robert Kurtzman and future Walking Dead director and Romero protégé Greg Nicotero — all walked down the Benedum’s red carpet, greeted by ushers decked out in zombie make-up.

And when Romero was introduced by his son, 3,000 people stood to applaud, to thank the man with clapping hands for all he’d done. For the world, for Pittsburgh, for horror in general. After the film, a huge after-party was held and even basketball great Michael Jordan made an appearance to show appreciation.

Goodbye George A Romero. We laughed through 50 years and 9 films. I will miss him. There is a light that has gone out and can't be replaced. pic.twitter.com/N0MAC1ItVM

— Tom Savini (@THETomSavini) July 16, 2017

His influence, however, can hardly be understated. Night of the Living Dead, for all of its detractors, legitimized horror for adult audiences. Long relegated to the stature of tax dodges and weekend shoots for the burgeoning teenage drive-in market, horror was despised prior to 1969, particularly by critics who saw no value. After Night of the Living Dead, attitudes changed. Look no further than the lasting global success of The Exorcist. Romero’s influence is all over that film in terms of stylistic choices on the part of director William Friedkin — so much of the first act shot documentary style — and the tonal choice of “this is happening, this is real, this could happen to you.” Look at Stephen Spielberg’s Jaws, the juggernaut that invented the Summer Blockbuster. So much of the movie has the shark unseen, a constant lurking menace, while the protagonists struggle to communicate and work with each other. Filmmakers were discovering new ways to both terrify the audience and make them question the world around them. Who has our best interests in mind? Who are we in times of crisis? Are any of us really as strong as we pretend to be? All of these used to be the domain of the serious drama. Now they’re coated in misdirection—the blood and horror the primary lure, the critique of civilization a bitter pill coated in candy trappings.

There will never be another filmmaker like George A. Romero, nor should there be, nor should we want there to be. His movies were the singular product of an excited mind, someone who saw an established genre and, to use an overextended phrase, reinvented it for his own devices. Without Romero, there would be no Resident Evil, there would be no Walking Dead. Without the love of those who grew up on Night, Dawn, and Day, zombies wouldn’t be the cultural phenomenon they are today. All because a group of friends wanted to make a movie. Because they said, “let’s do it this way and George should direct.”

Pittsburgh lost a favorite son. The Horror Community lost a Patron Saint. We are all the poorer for the loss. We are all the greater for his presence.

Mike Watt is a Pittsburgh filmmaker, author, and journalist. He worked with Romero's oldest son, Cameron, on his first feature, The Screening. He's covered the legacy of George A. Romero for such publications as Film Threat, Fangoria, and Cinefantastique Magazines. He recently edited a new version of Romero-collaborator John A. Russo's novelization of Night of the Living Dead.