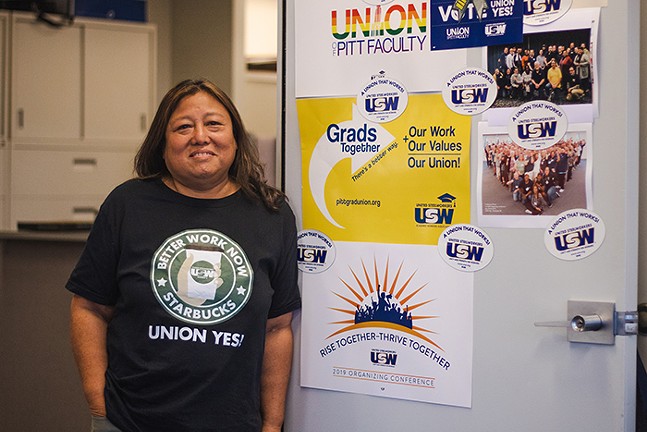

Six months ago, Tori Tambellini barely knew what a union was; now, the recent college graduate wants to devote her career to the labor movement.

Having worked as a barista throughout the coronavirus pandemic years, Tambellini helped found the union for Starbucks’ Market Square location this spring, after organizers from other shops convinced her it could give staff a voice in workplace issues they’d long felt excluded from.

She was fired six weeks later in a move she sees as thinly disguised retribution from her employer. Instead of feeling cowed, though, Tambellini feels confident and energized.

“It was honestly the worst union-busting strategy ever because I now have a job as an organizer with Workers United,” Tambellini tells Pittsburgh City Paper.

On Tuesday, staff members at Pittsburgh Community Broadcasting's sister radio stations WESA and WYEP became the latest in a wave of organizing service workers that has swept through Pittsburgh and the country during the last few years. Many of the leaders in recent unionization efforts say the drastic economic upheaval imposed during the early pandemic months shed new light on long-hidden inequities within the service industry, creating an opening for needed change.

The employees at WYEP and WESA filed to unionize with the support of national media representatives SAG-AFTRA, joining KDKA-TV producers who joined the guild in 2021, and workers at WPXI who announced an intention to join in February 2022.

"I hope that they’re going to recognize that this is something that’s good for the whole organization," says Rosemary Welsch, host of WYEP’s Afternoon Mix, who’s worked for the company since 1981. "This is not against anything, it is for something."

Shea Gannon, a former Starbucks’ colleague of Tambellini’s who was also recently fired after joining their union says the pandemic was “a big catalyst for a lot of people.”

“[Corporations are] benefiting so much from our hard work,” Gannon adds, “and it really feels like we’re being hung out to dry.”

So far, 11 Starbucks stores have unionized in the Pittsburgh area since the first successful Workers United chapter formed in Buffalo last December, giving the Steel City outsized representation among the roughly 300 union locations nationwide. No stores have yet won contracts, and reports from across the country suggest Starbucks is taking a hardline stance in hopes of stomping out the nascent movement.

In response, Tambellini says, organizers are focusing on boosting their ranks to help shift the balance of power away from corporate management and toward the more than 200,000 shop employees.

“I think a year from now, I’d like to see us continue to grow at the rate we’re currently growing,” she says during an interview immediately after the coffee chain’s Hampton location became the latest local store to win a union election.

Starbucks is just one of many service industry organizations where workers are unionizing in Pittsburgh and beyond.

Workers at Planned Parenthood of Western Pennsylvania formed a union in March 2021, requesting better pay and more resources long before the recent Roe v. Wade U.S. Supreme Court decision heaped new demands on reproductive health care workers in states like Pennsylvania, where abortion remains legal.

A few months later, 3,355 librarians and faculty formed a bargaining committee at the University of Pittsburgh through United Steelworkers, the Pittsburgh-based labor behemoth that has also led new unions for faculty at Duquesne, Point Park, and Robert Morris Universities, and also backs more than 300 Carnegie Library workers, who won a new contract earlier this year.

Last summer, 65 Pittsburgh-based tech workers contracted by Google won a three-year contract more than two years after they formed a union to fight for better pay and benefits. In July, workers at medical marijuana dispensary Cresco Sunnyside voted to join a Keystone State union of United Food and Commercial Workers.

Workers are using their education and training to outwit complacent corporations.

tweet this

In other cases, workers at small, privately-owned companies like South Side print shop Commonwealth Press and Pittsburgh-based coffee chain Coffee Tree Roasters have also recently joined the ranks of organized labor.

Lou Martin, a labor historian at Chatham University, says the emergence of these new union chapters reflects broader economic changes since the era of big coal and steel.

“I think the whole economy has shifted in some ways toward service, retail, distribution, those kinds of workers,” Martin tells City Paper. “And then the second group you have is librarians and university employees and professional classes. And one of the things they share, I think, in general, is both groups are probably pretty well educated.”

In turn, Martin says, workers are using their education and training to outwit complacent corporations.

But the latest wave of organizing hasn’t yet registered a reliable upward curve in union member numbers, which remain well below their high water mark in the mid-20th century.

Since 1964, for instance, union members nationwide have fallen from slightly under one-third share of the workforce to just one in 10 today, according to data gathered by economists Barry T. Hirsch and David A. Macpherson. In Pennsylvania, a state with deep labor roots, the same data shows union membership has fallen from about 38% of the working population in 1964 to around 13% in 2021. After falling precipitously during the latter 20th century, both state and national membership levels have essentially flatlined during the last decade.

The steady attrition of organized labor since the 1960s had led to a general consensus by the early 2000s that the movement would never regain its former vigor. A 2012 Atlantic article, Who Killed American Unions, is typical of its moment, where the movement was presumed dead, and studying its corpse could serve only to better understand its killers and their motives.

The tools of social media enable workers to expose the sorts of employer harassment that once took place behind closed doors, and win public support for their cause.

tweet this

“Today, unions have been swept into dusty corners of the U.S. workforce, such as Las Vegas casino cleaners and New York City hotel staff,” Atlantic staff writer Derek Thompson proclaims.

But the energetic organizers shaking up Pittsburgh’s coffee scene and its eds and meds corridor believe they’re part of a sustained resurgence in union influence nationwide.

“We see a whole slew of people from all walks of life who are coming in to show their support for the union,” Gannon says. “Which shows to me how public opinion is really swaying towards labor.”

Stephen Laskaris, president of the Carnegie Library system’s USW Local 9562, says many in his union were spurred on by the influence of union successes at local universities.

“The connections between organizations form a virtuous cycle,” he says, adding that they always try to turn out for events hosted by Starbucks workers because they view themselves “as part of a larger labor movement in Pittsburgh.”

Tambellini says the appearance of Steelworkers at an early union rally marked a turning point in their organizing efforts, particularly for older baristas, who, she says, were initially skeptical of younger employees' calls to unionize.

Maria Somma, organizing director for the United Steelworkers, began diversifying the international labor union’s membership long before the recent surge of service worker organizing. She was brought on about 20 years ago to help USW recruit members in the health care sector that she and others describe as the natural heir to the decimated steel industry.

“I look at today in the city of Pittsburgh, and the mills that used to be here, that used to employ hundreds of thousands of workers, those mills have been replaced by eds and meds,” Somma tells City Paper. “I call the eds and meds economy the steel mills of today … So our [industrial model] has remained true, but the employers that we choose now may look differently than U.S. Steel.”

Somma has helped form the university and library unions under the USW banner and says she stands with Starbucks and other hospitality organizers aligned with different union structures. But she says the future hinges largely on whether federal laws and policies will bend to the surging grassroots movement.

Summer Lee, a state representative and congressional candidate, says the recent organizing efforts are working “hand-in-hand” with a “wave of progressive electoral organizing” that swept her into office in 2018.

“The labor movement is doing their job — they're organizing, they're marching and they're telling politicians exactly what they need,” Lee tells City Paper in an email. “Now, it's Congress' duty to deliver on those promises to workers and unions, first and foremost by passing the PRO Act and ensuring that every worker's right to form a union is protected at the federal level, and[then] reverse the anti-worker ‘right-to-work’ laws in 27 states across America.”

According to Martin, a package of amendments made to the 1935 National Labor Act by a Republican congress in 1947 left unions permanently vulnerable to so-called union-busting tactics.

“I look at today in the city of Pittsburgh, and the mills that used to be here, that used to employ hundreds of thousands of workers, those mills have been replaced by eds and meds.”

tweet this

Known as the Taft-Harley Act, the amendment weakened the initial legislation in several ways, most keenly, Martin says, by repealing a provision that formerly prohibited employers from attempting to influence workers during negotiations. “And so that opened the door to all kinds of propaganda being showered on employees,” he says.

Later, Martin says, consultancy firms exploited these weaknesses, finding a reliable cash cow in corporations looking to crush organized labor.

But now, Martin says, the tools of social media enable workers to expose the sorts of employer harassment that once took place behind closed doors, and win public support for their cause.

“So I would say that with social media, the HR departments and anti-union law firms have been outmaneuvered,” he says.

The shift in workforce representation is also presaging a shift in union politics and identity.

In 1935, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt assembled a powerful voting coalition known as the New Deal Democrats that cemented the relationship between his party and the working class, prompting more than a decade of steady labor gains. According to a 2008 paper by the Brookings Institute tracing the history of the white working class, the New Deal era began to attract Black voters — who mostly still sided with Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party — to the Democratic Party, but as a whole, labor culture remained predominantly white, and largely moderate, or even conservative on social issues in the decades to come.

To see the transition of really kind of open arms and acceptance of a lot of things that people wouldn't traditionally think about in an industrial union has been a wonderful experience for me."

tweet this

Somma, a Vietnam native, says today’s union workers, particularly outside the manufacturing sector, lean much more progressive than their New Deal ancestors. In recognition of this shift, Somma says USW adopted a string of inclusive language and policies during its most recent annual convention in early August.

“To see the transition of really kind of open arms and acceptance of a lot of things that people wouldn't traditionally think about in an industrial union has been a wonderful experience for me,” she says. “Because I'm an immigrant.”

Martin says for the emerging service worker movement to build enduring political clout, it will need to learn other lessons from past labor failures.

Historically, Martin says, rank and file union members were often left in the dark by a small group of insiders who headed their bargaining strategies. The sense of disenfranchisement this generated weakened unions’ internal unity, and in turn, their external leverage.

Now, rather than “the old cigar-chomping kind of union boss” of times past, Martin says, emerging unions should be wary of “the guy who rose through the ranks and wears the three-piece suit and has lawyers and researchers on the negotiating team.”

“You're already dealing with some people who are frustrated and cynical, you know, and if unions turn out to be just as closed and undemocratic as corporations, I think you'll see a lot of this could just be a blip,” he says. “And I hope that's not the case.”

Lee similarly says the labor movement rests on the strength and diversity of its adherents.

“We can only deliver on the promises of our progressive movement with a strong multiracial, multigenerational labor movement by our side,” she says. “From successful organizing at Amazon to Starbucks right here in Pittsburgh, workers are meeting the 21st century moment for our labor movement and now Congress must codify that organizing power into law."