On the surface, King Hu’s 1967 film Dragon Inn and Tsai Ming-Liang’s 2003 film Goodbye, Dragon Inn could not be any more disparate.

Dragon Inn, playing Sat., March 19-Wed., March 23 at Downtown’s Harris Theater, is what’s known as a wuxia film, a genre preoccupied with tales of martial artists in ancient China. And yet for a genre so concerned with the distant past, wuxia’s popularity in China is not premised strictly on nostalgia.

Unlike the traditional Confucian virtues that characterized Chinese culture prior to the 20th century, the heroes of wuxia films are supreme individualists in the same way the heroes of American Westerns are. The only law or code they follow is their own ethical sense, and it’s this ethical sense that justifies the spectacularly choreographed violence that’s at the core of Hu’s film. The plot is paper-thin — a villainous eunuch sentences Yu Quan, an unfortunate but loyal minister, to death, and then commands his soldiers finish the job by killing his children. But have no fear: a group of outlaws with hearts of gold, loyal to the late minister, takes up the task of defending them, and do so with panache.

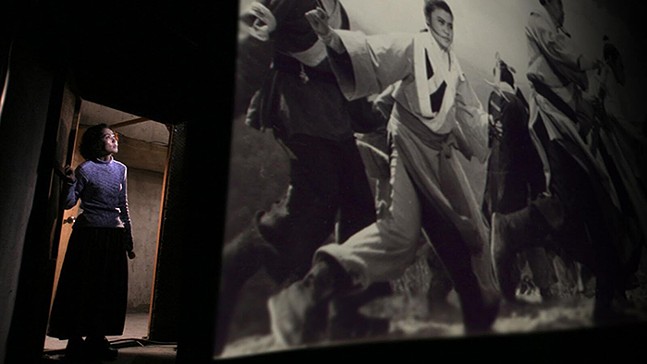

Getting any more into the plot is a waste of time, mostly because I barely remember it beyond what I’ve just recalled. If anything, Dragon Inn embittered me against the soggy, plot-laden action movies we settle for now — so long! so badly lit! so boring! — because, by comparison, they lack any real style or flair. Hu’s film is style all over; there’s a real feeling for color and beauty at work. The enemy soldiers don bright red sashes over dark blue robes, in contrast to the pale colors the heroes are adorned in. When blood is drawn (which it is frequently), bright red paints their costumes in artful little streaks. And Hu has a keen awareness of the camera, turning it into a floating eye he’s unafraid to set in motion. The camera tracks even the subtlest movements, following the swordsmen as they move towards an enemy to strike, and then darting away with them when a blow lands. The editing aligns with this, too. The rapid movements of the heroes are highlighted by quick cuts that in turn enhance the kinetic energy of the camerawork.

If Dragon Inn is distinguished by a strong dynamic sense, then it follows that a film titled Goodbye, Dragon Inn might be distinguished by the opposite. Tsai’s film, which plays Fri., March 18-Thu., March 24 at the Harris, featuring three back-to-back screenings with Dragon Inn, is still — I cannot emphasize enough how still it is, and in more ways than one. Ostensibly about the last days of a Taiwanese movie theater showing the film Dragon Inn, the “plot” of Goodbye, Dragon Inn is as nonexistent as Dragon Inn’s plot is irrelevant. There are maybe ten lines of dialogue in the entire film, which is populated by mostly nameless characters who wander the decaying theater.

This description makes it out to be a dour and unforgiving movie; it’s a good thing that movies don’t live and die on their basic description. Because beneath the steely surface of Tsai’s aesthetic, Goodbye, Dragon Inn reveals itself to be full of the little plots that make up life as we understand it. A day at the movies isn’t just a day at the movies; it’s the discomfort of a person sitting next to you in an otherwise empty theater, the man moved to silent tears by a something you can’t comprehend, the way a woman crunching peanuts loudly a few rows ahead can become your own existential torture.

The sequence with the peanut-crunching woman is, on its own, enough to disprove the idea that the film is all gloom. The humor is comparable to Jacques Tati’s Playtime, another genius movie that made the foibles of everyday existence into grand set pieces. Tsai arranges the sound design so that Dragon Inn’s soundtrack takes a backseat to the increasingly nerve wracking sound of the woman’s teeth breaking the shells, and then the clatter of them hitting the floor. When she climbs over her seat into the row behind the man we’ve been made to identify with, searching for a peanut accidentally dropped to the floor uneaten, the sound of her crunching gets louder and louder and the man’s discomfort more and more evident. The music gets eerie, and, before we know it, the man is darting out of the theater, crunching himself as he steps on a sea of shells littering the stairs.

By drawing the moment out into a long sequence, Tsai not only reveals the operatic quality living in all our experience, but captures it and sends it back to us — transformed just enough for us to recognize it in ourselves. Though I didn’t recognize it until after I finished Tsai’s film, the man weeping while watching Dragon Inn is, in fact, the star of King Hu’s film. Walking out of the theater at the end of Goodbye, Dragon Inn, he encounters another actor from the film, and says to him: “No one goes to the movies anymore. And no one remembers us anymore.” Maybe that is the gift movies give us, even if they’re too dull and bloated for us to identify it most of the time. We can sit there and remember how bright a color can be, how painful a sound can be, and how moving and funny life can be — but only if we give ourselves the time to see it.

Goodbye, Dragon Inn. 5 p.m. Fri., March 18. Continues through Thu., March 24. $11. (Special double-feature pricing is available when purchasing both Dragon Inn and Goodbye, Dragon Inn on March 19, 20, and 23.) Harris Theater. 809 Liberty Ave., Downtown. trustarts.org (Goodbye, Dragon Inn) trustarts.org (Dragon Inn)