Ask Americans which President Roosevelt was the biggest conservationist and most would say “Teddy.” But as historian Douglas Brinkley demonstrates in his book Rightful Heritage: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Land of America, a better answer might well be FDR, who added so dramatically to his famous older cousin’s legacy.

The book, released this past spring, introduces an FDR few know: not just the wheelchair-using master politician, the fireside-chatter who guided the nation through the Great Depression and World War II, but also a life-long tree farmer whose passion for forestry and soil conservation informed his entire career. “His alternate occupation was forestry,” says Brinkley in a phone interview.

TR, it’s true, almost single-handedly launched the modern era of conservation by creating numerous national parks, national monuments and national forests, most of them out West, from 1901-1909. (Accounts include 2009’s The Wilderness Warrior, one of Brinkley’s 22 works of nonfiction.) FDR, who took office in 1933, created more than 800 state parks — including, Brinkley notes, essentially the entire state-park system in Texas, where he teaches at Rice University — as well as an all-star line-up of national parks. “FDR’s responsible for saving the Great Smokies, the Everglades, Big Bend, Joshua Tree, Channel Islands, the Olympics, Jackson Hole, Mammoth Cave, Isle Royale, on and on,” says Brinkley, who visits Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures’ Monday Night Lectures on Nov. 21. The 32nd president also expanded many more national parks, created hundreds of national forests and wildlife refuges, and launched the modern U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Still, Brinkley argues that perhaps FDR’s signal environmental achievement as president was the Civilian Conservation Corps. While it provided wages, job skills, hot meals and hope to more than 3 million workers over its nine-year life span, this quintessential New Deal entity was more than just an employment program: “Roosevelt’s Tree Army” planted up to 3 billion trees, reclaimed millions of acres from deforestation, overfarming, erosion and drought, and built the roads and facilities that made countless natural areas accessible to ordinary Americans, with a focus on the more densely populated East Coast.

FDR grew up in upstate New York, son of an affluent gentleman farmer, and early learned the importance of healthy soil and the multiple benefits that trees provide: remediating stormwater, preventing erosion, providing wildlife habitat, even reclaiming depleted land. “They were the symbol of life, trees, for FDR,” says Brinkley. After contracting polio at age 39, Roosevelt was paralyzed from the waist down for life, but remained an avid fisherman and automobile road-tripper. And his plans to preserve and restore nature grew, rather presciently, to include “submarginal” (i.e., unfarmable) land that most people — including past presidents — had written off. “Nobody in American history has done more for wetlands and marshes and seashores than Franklin Roosevelt,” Brinkley says.

Such initiatives inspired, trained and gave opportunities to a generation of environmental advocates, including a young federal aquatic biologist named Rachel Carson.

In the eyes of today’s environmentalists, and even some in his day, FDR’s record is indelibly marred by his fondness for large-scale hydroelectric dams: Projects like the Grand Coulee Dam, in Washington, decimated salmon runs and flooded huge stretches of river-valley ecosystems with artificial lakes.

Still, the scope of his conservation achievements is astounding, especially given that most of them were accomplished during the nation’s worst-ever economic crisis.

Or maybe, in a way, that’s not so surprising. We’re used to hearing environmental protection criticized as bad for the economy. But Roosevelt, as Brinkley shows, had a genius for framing conservation as economic development.

Partly, this was a matter of providing work, as through the CCC, partly it involved improving the lot of farmers, whose language FDR spoke. “It wasn’t just that Wall Street was exhausted, and the banks had foreclosed, but our agricultural sector was in dire straits,” says Brinkley. But it was also about recreational development. “In states like Pennsylvania, Vermont or Idaho, FDR would dispatch government workers to build ski resorts, to create picnic sites, to stock streams and lakes with fish,” says Brinkley. “He was really trying to bring conservation close to home.” The CCC alone developed 52,000 acres of public campgrounds. Even new wildlife refuges meant that hunters enjoyed revived populations of ducks and geese.

FDR acknowledged that greed could ravage nature; one reason he liked hydropower so much, after all, was the damage he’d seen done by coal mining. But ultimately, to him, environmental protection and economic growth weren’t mutually exclusive. They were complementary.

“He put conservation at the top of his list and national-revitalization efforts. He didn’t downplay it,” says Brinkley. “He upgraded it.”

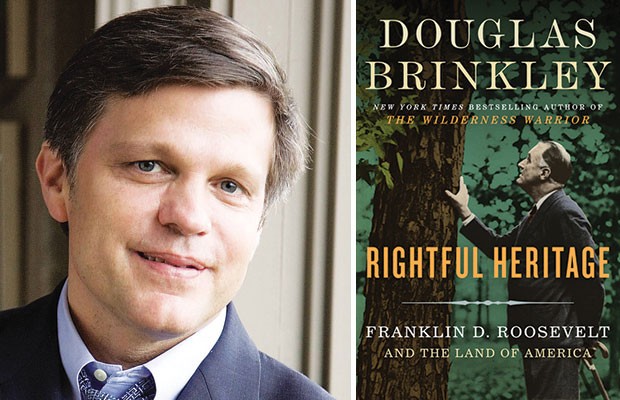

Historian Douglas Brinkley talks about Franklin Roosevelt’s environmental ethic

“They were the symbol of life, trees, for FDR.”

Douglas Brinkley