More people in the United States are now dying from drug overdoses than from either car accidents or firearms. It has been this way since 2008, according to federal statistics, and the gap has widened each year. It’s an epidemic — with heroin and other opiates causing the majority of these deaths. In his State of the Union address this year, President Obama called heroin a public-health crisis.

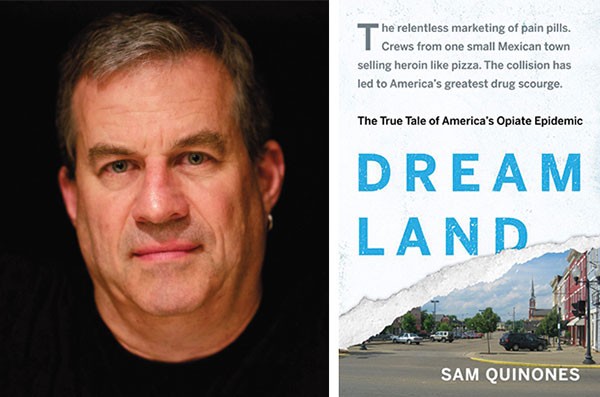

Sam Quinones’ 2015 book Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic tells the frightening story of how this problem has evolved over the past 40 years. In Dreamland, the former Los Angeles Times reporter — who speaks here Oct. 26 at a fundraiser for Gateway Rehabilitation Center — seeks to uncover the roots of this epidemic, about which his book’s title suggests that there is a false tale.

But indeed, many observers’ chief culprit — prescription painkillers like OxyContin, which eight of 10 heroin addicts start out by using — isn’t so much a false story as it is only a fraction of the complete story.

“It needed to be brought together in a coherent narrative, that’s what had not happened,” says Quinones in a phone interview. Dreamland argues that the true beginning of the epidemic isn’t in 1996, with the commercial release of OxyContin, but almost two decades earlier, when the medical community changed its attitude toward the treatment of pain.

This story starts in 1979, when a doctor at Boston University named Hershel Jick grew curious about addiction rates in patients treated with painkillers. He and a graduate student named Jane Porter searched a university database. It was not a true medical study, nor was it meant to be. Jick sent his findings in a handwritten letter to the editor at the New England Journal of Medicine. Shortly after, this statistic appeared as a one-paragraph blurb on page 123 of the journal: Out of nearly 12,000 hospitalized patients treated with opiate painkillers, only four had become addicted.

“Porter and Jick,” as the study became known, effected a dramatic shift in the medical community’s attitude toward the treatment of pain. It calls to mind Mark Twain’s saying that “there are lies, damned lies, and statistics.” Jick’s data came from information collected haphazardly, with no follow-through as to the status of patients after dismissal — which is really the only time when addiction would appear. Simply put, this data misled.

Doctors were actually already aware of this. Before the 1980s, doctors had been averse to prescribing opiates simply because of how addictive they knew them to be. But Quinones deftly explains how Porter and Jick’s findings were used as “evidence” to overturn the prevailing and conservative stance on pain.

“The linchpin is the pain specialists,” Quinones said when I asked him how so many doctors were swayed. It was pain specialists who argued that doctors were missing out on a chance to help patients because of their fear of addiction. To not treat pain was cruel. Pain became the fifth vital sign. And state by state, legislation was passed to protect doctors from prosecution if they prescribed opiates for pain. Enter OxyContin. It was in this climate that Purdue Pharma released the drug and doctors began to prescribe it wildly beyond anything that any doctor would have imagined a decade earlier.

Today, the epidemic might be a national crisis, but Pittsburgh has been on the frontlines from the beginning, says Quinones. “There’s a place where this stuff started, and it’s not far from Pittsburgh.” Indeed, in 2014, our city made national news when 22 people died from overdoses in one week. In the past few years, it’s been hard to watch the evening news without coming across a story about heroin. Between the daily arrests and frequent warnings about overdoses from contaminated heroin, it’s become an unavoidable issue that directly affects many people and indirectly affects us all. And the Pittsburgh region has become one of the hardest-hit areas in the country. According to 2014 statistics from the Centers for Disease Control, Pennsylvania has the eighth most overdose deaths in the country (West Virginia was first and Ohio fifth), while Pittsburgh ranks 18th among American cities.

Quinones’s book does offer a silver lining: our resilience in the face of tragedy. He recounts how small towns like Portsmouth, Ohio, ravaged for years by drugs, formed organizations, charities and school programs to fight back. “Dreamland,” in fact, is the name of the community pool that was the center of social life in Portsmouth until the 1980s. Quinones connects the dots between mistakes made decades ago and the problems communities face today. But if the first step to solving any problem is admitting it exists, maybe the second step is learning from those mistakes to help heal from them.