Seems like just about everyone is a multi-hyphenate these days. Whether you brand yourself as an actor/director/musician or artist/filmmaker/vintner or barista/poet/furniture-maker, clearly one talent is no longer adequate. It used to be that mostly only creative types had composite careers, sometimes to support themselves in their artistic endeavors and sometimes, as Primo Levi explained in an interview with Philip Roth, to keep “in touch with the world of real things.”

Generally it’s the economy that dictates the need for multiple jobs, but it is also quite the trend. For celebrities, in particular, it offers both diversified revenue and a certain cachet. There are actors, musicians and directors who are also visual artists and visual artists who are also film directors. Some of them are enviously proficient at their multiple crafts. But others, no doubt, are lauded simply because they already have some kind of recognition.

There is probably no better place to contemplate this than at The Andy Warhol Museum. Was there anyone more adept at documenting and cultivating fame and celebrity in multiple platforms? And who among his coterie were truly talented and who were either just ambitious or just plain famous for being famous?

Hence, the exhibition Michael Chow aka Zhou Yinghua: Voice for My Father, is a perfect fit for the Warhol. First shown at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, and then the Power Station of Art, Shanghai, the exhibition is Chow’s first solo show in the U.S. since he began painting again after a 50-year hiatus as a successful celebrity restaurateur. Like Warhol, Chow’s personal story is mythic and he has cultivated a persona that is inseparable from his brand.

As a friend and patron to many artists, Chow amassed a collection of portraits of himself. One by Warhol from 1984, a black-and-white silkscreen diptych, sits at the entrance to the exhibition. Designed in three parts, the exhibition includes a section of portraits of Chow by several other artists including Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Peter Blake and Ed Ruscha. The other two parts are large-scale paintings by Chow in dialogue with 111 vintage photographs of his father, Zhou Xinfang, a grand master of Beijing Opera who performed and also took on roles as director, screenwriter and theater manager over his 60-year career.

Chow led a cultured and pampered life in Shanghai before his parents sent him to boarding school in England, at the age of 12. He never saw his father again because despite his celebrity in China, Zhou was imprisoned in 1968 during the Cultural Revolution and remained under house arrest until his death, in 1975.

The exhibition is a tribute and a gift from son to father, and it is impossible to appreciate it without an understanding of their remarkable stories. In her catalogue essay, Christina Yu Yu writes, “While it is tempting to investigate the psychological causes of this unusual phenomenon — the late blooming — we would be ill-advised to do so, as Michael Chow is very much in charge of this effusion of challenging paintings.” But there is no way to avoid a bit of psychoanalysis. In 2012, after a nudge from his friend Jeffrey Deitch, the art-dealer and one-time director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Chow began painting again, “obsessively,” according to an interview with his wife Eva. Like his restaurants, the paintings play out as a latent quest for paternal approval born of the trauma of separation. In wall text, Chow explains: “My whole life has been trying to create something that could recreate the extraordinary world I knew as a child. And I have done all of this in order to prove to my father that it could be done.”

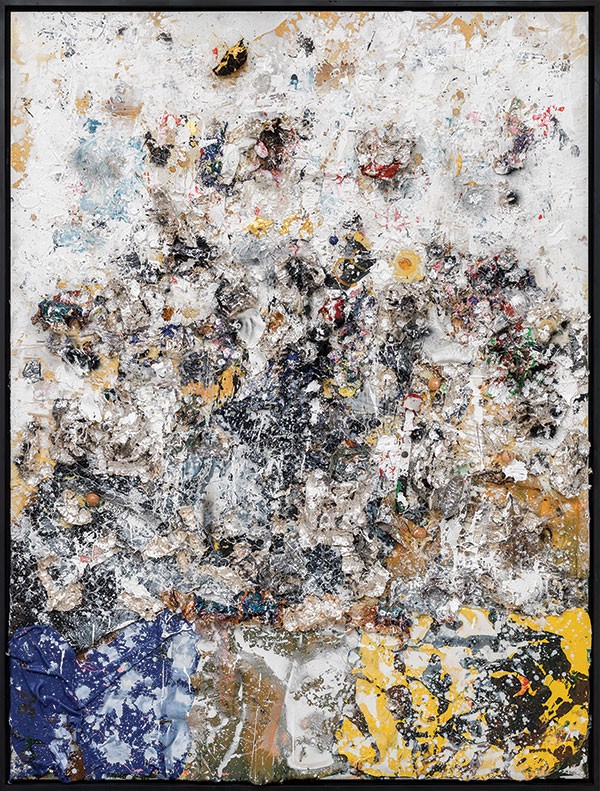

And much like his restaurants, his paintings, all abstracts, are a mélange of orchestrated theatrics. Pretty much anything you can imagine has found its way onto his out-sized canvases — burnt plastic wrap, gold foil, money, rubber gloves, sponges, leaves, tires and even raw eggs share frenetic space with pours, washes, and drips of mostly white house paint. The paintings combine aspects of East and West and grapple with the feelings of rupture common among exiles. In conversation with his father’s photographs they speak of loss, mourning and death, but they also celebrate the creative collage that is his life, the pain and the joy.

Surrounded by creativity at an early age, Chow had the uncanny ability to be at the epicenter of art, fashion, film and celebrity in London in the 1960s, and then later in Los Angeles and New York. In the process he became famous for being famous among the famous, and over the decades he soaked it in and poured it back into a painting career cut short in 1962.