During the 23 years he has served of his life sentence, the Pittsburgh native says he has spent more than $3,500 on first-class mail, sending his story to anyone who will listen, anyone who can help amplify his plea of innocence. This includes celebrities like Whoopie Goldberg and Tyler Perry, as well as previous staffers of former President Barack Obama.

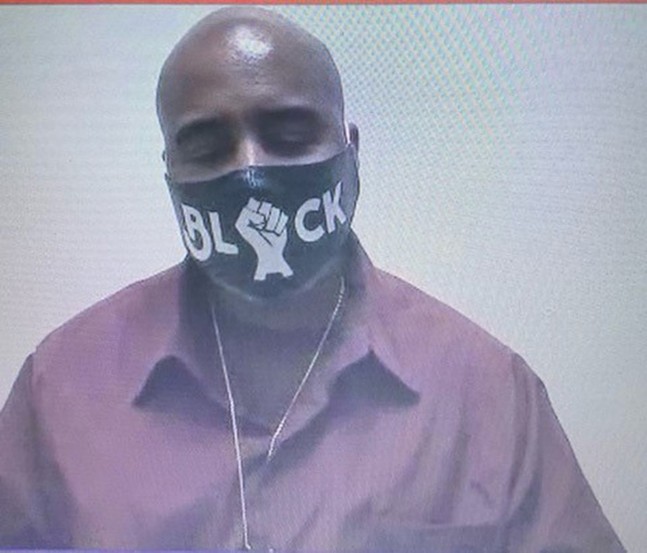

“Anybody that I can see on CNN, law professors, whoever,” says Daniels, by phone from SCI Forest. “Anybody that I can see who might be able to help.”

Daniels was convicted of first-degree homicide in 1998, for the 1994 shooting and killing of Ronald Hawkins, a jitney driver on the North Side. Daniels has proclaimed his innocence since the beginning and has built up a case over the years, trying to overturn his conviction. He has found eyewitnesses to sign affidavits that counter eyewitness testimony used in his trial. Daniels has taught himself many aspects of criminal defense law, and filed several appeals.

“It took me, like, five years to truly learn it,” says Daniels of some intricacies of Pennsylvania criminal law. “When you are an innocent person in jail, it is hard to take it.”

His partner Crystal Daniels has helped him along the way, and some family members have assisted in tracking down sources that might help his defense. He has also hired lawyers to file appeals and petitions, as well as reached out to just about every group who works to help exonerate prisoners that one might think of.

This effort doesn’t guarantee that Daniels will be ruled innocent or be granted his freedom, and courts have already rejected many of his appeals, finding his affidavits not credible. But according to criminal justice advocates, the obstacles that Daniels faces are common. Conservative estimates put the number of improper convictions in the tens of thousands each year in America. There could be hundreds, if not thousands, of cases similar to Daniels vying for attention at the same time.

For Daniels, part of his struggle has been getting the necessary attention that might catapult his case into the limelight, and the resources that usually follow. He, along with Crystal, have contacted advocacy groups, lawyers, and local and national journalists, but to no serious avail. Daniels says some journalists or advocates have started to look into his case, but it has never led to anything. Whether that’s because he’s being ignored, or his case just isn't strong enough to pursue, may be hard to determine. Either way, Daniels isn’t giving up hope. Facing a life sentence with no possibility of parole, he is determined to fight for his justice.

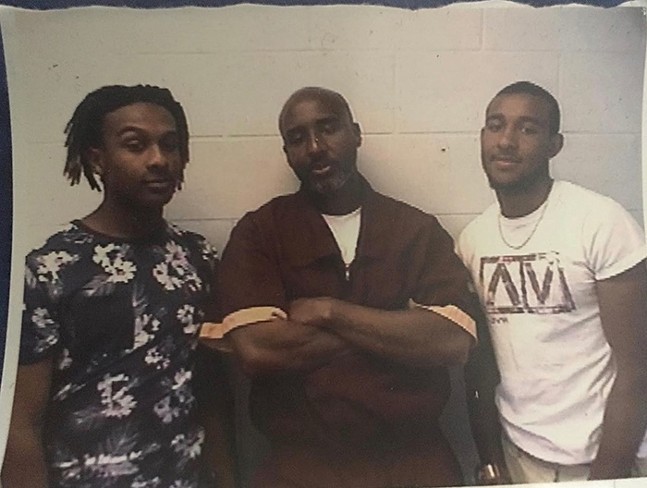

“I am not bred to accept defeat,” says Daniels. “I can’t see my kids. I can’t accept defeat for my family. ... It is heartbreaking. I lost my dad since I am here. My kids are growing up. You got to really dig deep to lean on the Lord.”

Pittsburgh City Paper was made aware of Daniels’ story thanks to 1Hood Media, an advocacy organization focused on amplifying Black voices and serving Pittsburgh’s Black community. Daniels says he saw 1Hood on TV and decided to reach out to the group last year.

Daniels grew up in Pittsburgh and graduated from Perry High School in 1989. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy shortly after that, and he saw action in Operation Desert Storm in the Middle East. Daniels has four children, who are now adults and live in different parts of Pennsylvania and the country.

After returning to Pittsburgh following his military service, Daniels admits that he started to deal drugs as a way to make money. He admits that this and his other crimes were wrong, and noted he has already served the time for his other convictions, which include carrying a firearm without a license and engaging in criminal conspiracy. Daniels was not convicted of any drug-related charges. His record before his homicide conviction included a 1994 guilty plea to a simple assault misdemeanor, which resulted in a probation sentence.

“It was the wrong thing to do,” says Daniels. “I tried to shortcut the system. I knew I was destroying the community, but we got to eat. But it was the wrong way.”

When he was charged for Hawkins’ killing, Daniels went on the lam to Michigan and other states across the U.S. He says he had little faith in the criminal justice system, and that feeling was strengthened since his trial kept starting and stopping over the years. Daniels says this gave him the impression the prosecution didn’t have sufficient evidence to convict him, but that they were fishing for more.

“I was trying to figure out what was going on,” says Daniels of his fleeing the state after being charged. “Every time they wanted to go on trial, they wouldn’t go.”

While out of state, Daniels met Crystal in Seattle in 1997. Crystal, who still lives in Seattle, says they have been together ever since. The two aren’t married (the same last names are just a coincidence), but Crystal says she has stood by Daniels because she believes in his innocence.

Crystal says she has helped Daniels contact television shows, journalists, lawyers, criminal justice experts, celebrities — anyone who Daniels and Crystal think might take up his cause. For the vast majority of instances, Crystal hasn’t received any response.

“Oh my gosh, it’s been so difficult,” she says. “I don’t know how many emails I have sent out and gotten zero response.”

Daniels agrees it has been an intense struggle to get any outside attention to his case. He says he has, at times, made a bit of headway with journalists, but eventually communication goes silent. Crystal says the two of them have reached out to several groups focused on helping to exonerate prisoners, like the PA Innocence Project, and at times his case has been accepted, but also hasn’t led to anything substantial.

It is understandably difficult to get people invested in Daniels’ case. The shooting occurred more than 27 years ago, and Daniels has appealed his conviction and related rulings every step of the way, and while courts have at times agreed with him, ultimately, his cases were rejected.

In 1998, after law enforcement arrested him in Georgia and brought him back to Pennsylvania for his trial, a jury found Daniels guilty of first-degree homicide, four years after the shooting death of Hawkins. According to a 2017 opinion from the Allegheny County Common Pleas Court, Daniels and two of his companions drew guns on Sept. 20, 1994, and ran towards a dark gray Buick driven by Hawkins, then fired their guns into the Buick, killing Hawkins.

The commonwealth’s case against Daniels included two eyewitnesses who said they saw Daniels commit the shooting. Daniels believes these eyewitnesses were coerced, and he has filed petitions to have other eyewitness testimony be allowed to be submitted as evidence to his case through the state’s Post Conviction Relief Act.

Daniels has filed five petitions through the PCRA. The PCRA allows prisoners and those convicted of crimes to file direct appeals, asking the court to reconsider their conviction.

All five petitions have been rejected, though some made it up to the state Supreme Court through appeals. The 2017 opinion from the Allegheny County Common Pleas Court found two of Daniel’s eyewitnesses — who claimed that Hawkins was shot in a drive-by, not by perpetrators on foot — not to be credible, citing inconsistencies in their testimony and that testimony was given too far from the date of the shooting.

Daniels says there is other evidence that backs up his case, like an alleged 911 call from the night of the shooting that corroborates the eyewitness testimony he provided. As part of his research, he also found out years later that he went to high school with one of the members of the jury and wonders why that wasn’t disclosed during his trial. Even through all the rejected appeals, Daniels continues to proclaim his innocence.

“I was a guy that wanted to do great things, but I chose the wrong decisions,” says Daniels. “But I didn't kill Mr. Hawkins.”

The country is also in a different place than it was even just a few years ago. Recent events, protests, and civil rights actions indicate how the country is undergoing an awakening. The Black Lives Matter movement has shifted the way Americans think and talk about criminal justice. It’s become a more common form of activism to help exonerate people for crimes the country now sees as overly punitive, or to help determine wrongful convictions.

“The fact that he has been incarcerated for two decades for a crime he alleges he didn't commit is sad. But tragically, it is kind of normal.”

tweet this

Elizabeth DeLosa is the managing attorney for the Pittsburgh office of the PA Innocence Project, a nonprofit that works to exonerate innocent prisoners and those convicted of crimes they didn’t commit.

She says that Daniels’ story is not uncommon, and that there are many people convicted of crimes vying for their innocence, even just in the Pittsburgh area.

“Unfortunately it is more common than we would like to admit,” says DeLosa. “It is happening to Mr. Daniels, but it is also happening to many, many people in Allegheny County. … The fact that he has been incarcerated for two decades for a crime he alleges he didn't commit is sad. But tragically, it is kind of normal.”

DeLosa says experts estimate that between 3% and 10% of people convicted of crimes in America each year are innocent. She says even by making those estimates more conservative — such as 1% — would mean that about 10,000 innocent people are convicted annually in the U.S.

On top of that, Pennsylvania law requires that people convicted of 1st and 2nd degree homicide serve life sentence with no possibility of parole. They are sentenced to die in prison. Only through commutation — a change of a sentence to one that is less severe — can those serving life sentences be given a chance to speak to a parole board.

She notes that Pennsylvania has very strict post-conviction laws, and even the people that PA Innocence Project has helped exonerate still average about 18 years in prison.

DeLosa notes convictions based on eyewitness testimony, like in Daniels’ case, are relatively common in wrongful convictions cases, and notes that the trial system can be daunting for defendants. She says portions of the homicide case file don’t get turned over to the defense during discovery. So if there were other witnesses who spoke to police that counter the prosecution’s eyewitness testimony, the defense may never be made aware of that.

Daniels did eventually find additional eyewitnesses willing to testify, but it was years later and Pennsylvania courts have timeliness standards that can obstruct getting those eyewitness testimony included. Basically, it’s extremely hard to convince courts of innocence after conviction.

PA Innocence Project understands this, and has an incredibly rigorous process in taking on cases. DeLosa says the project gets about 500 cases a year just in the commonwealth. Those then move through a questionnaire process, followed by the project’s lawyers reviewing a case to look for red flags, like when the only thing that connects someone to a crime is an eyewitness.

If a case has enough red flags, the project will do a deep dive into items such as documents and witnesses. After that, the case will be presented to a panel created by the Innocence Project constructed of a criminal defense attorney, at least one prosecutor, and others. Only if the panel approves, will the Innocence Project move forward with a case.

Since its creation in 2009, the PA Innocence Project has successfully exonerated 20 people, or about two people a year.

Crystal says they have reached out to the PA Innocence Project, but have not heard back regarding Daniels’ case. Despite dozens and dozens of attempts to get attention for Daniels’ case, the only story written about his innocence claims came from a 2020 article in a prison abolition advocacy magazine called “The Movement.”

After 23 years behind bars, Daniels understands just how demoralizing being incarcerated can be, especially when believing in one’s own innocence. He says many fellow imprisoned individuals will stop fighting eventually.

“Half of the people in here are on medication and they just give up,” says Daniels. “But if you can get your mind on fighting the injustices that is something. It’s something.”