Pittsburgh, we're told, didn't much go for modern art until the 1950s. That was when the Carnegie Museum of Art's Carnegie International, for example, really began to embrace abstraction, surrealism and other 20th-century forms.

But there's a bit more to the story, as Cayce Mell began learning in 2009, after some typewritten sheets of paper slipped from a library book she had opened.

The pages, rather eerily, had been typed a lifetime earlier by Mell's own grandmother, Betty Rockwell. Nearly as shocking, the text documented the existence of a place most everyone alive had forgotten: Outlines, Pittsburgh's first gallery of avant-garde art, founded Downtown by Rockwell in 1941, years before anyone would have thought such a thing possible.

Nor — at a time when modern art was widely seen as morally suspect and politically subversive — was Outlines just any gallery. Over six years, Rockwell showed work by an avant-garde who's-who, ranging from the famous (Picasso) to such then-obscure future icons as Jackson Pollock, Alexander Calder, Joseph Cornell and Georgia O'Keefe. (Others on the list: Francis Bacon, Henry Moore, Ashile Gorky, Dali, Magritte, Mondrian, Klee.) Many of these artists weren't even names in New York City yet.

Moreover, well before it was fashionable, Rockwell exhibited fine-art works of photography, furniture, industrial design — even commercial art. She screened experimental films by the likes of Maya Deren; hosted a lecture by Langston Hughes; and offered classes taught, early in their careers, by groundbreaking composer John Cage and dance pioneer Merce Cunningham.

"It's mind-blowing, it's jaw-dropping," nationally known art critic Blake Gopnik has said of Rockwell's achievement. Gopnik says that Outlines was, in its day, "one of the most important international galleries in North America" — and among the best in the world.

Gopnik is one of the experts quoted in Tracing Outlines, the feature-length documentary that Cayce Mell began making shortly after finding those papers. The film, produced by Scott Sullivan, gets it first public screening on May 21, at the Carnegie Museum of Art. Mell's project was aided immeasurably by her rediscovery of the "meticulous" scrapbook that Betty Rockwell kept on Outlines ... but which had sat in a drawer at the Carnegie for more than a decade following Rockwell's death, in 1998.

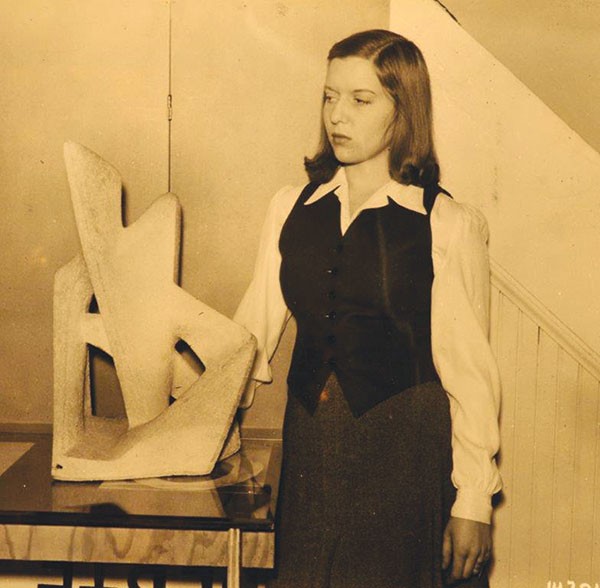

Rockwell was the youngest child of the Pittsburgh-based industrialist who started the company that became aerospace giant Rockwell International. She founded Outlines at age 21, with $1,000 in college-graduation money. Rockwell closed Outlines in 1947, by which time it had moved twice: first from 341 Boulevard of the Allies to the second floor of Oakland's Pittsburgh Playhouse, then back Downtown. But the six decades of oblivion to which the gallery was consigned in death might have stung Rockwell less than its reception while alive.

For instance, though Rockwell sent 100 fancy invitations to Outlines' inaugural press reception, "no one" came, she recalled. Her scrapbook proves that the local and regional press did cover Outlines. But many of the yellowing headlines today sound either condescending — "Art Gallery Opened by Girl" — or uncomprehending: "Weird French Film Shown at Outlines," says a review of Jean Cocteau's surrealist classic The Blood of a Poet.

Rockwell herself estimated that "maybe a hundred" Pittsburghers frequented Outlines. After it closed, her busy life included raising three daughters and, in 1971, founding the Society for Contemporary Craft (which lives on in the Strip District). But Mell guesses that, even before she developed the brain tumor that incapacitated her, Rockwell "didn't discuss [Outlines] because it was painful."

Ironically, Mell says, Outlines shut its doors just as post-war America was beginning to regard modern art not as a pariah, but as "part of everyday life," its styles echoed in film, furniture and food packaging.

As Robert Manley, of Christie's Auction House, says in Tracing Outlines, Rockwell opened her gallery "just a little too soon."

But that's not quite the whole story, either. That small band of Outlines devotees included artist Balcomb Greene, who taught at the Carnegie Institute of Technology and often took students to exhibits. Those students include famed painter Philip Pearlstein, who in Tracing Outlines recalls visiting the gallery with his classmate Andy Warhola. And in the film, critic Gopnik — who's writing a biography of Andy Warhol — speculates that Rockwell's venue was where Warhol got the idea to do silkscreen as painting. More than that, according to Gopnik's educated guess, Warhol "learned how to be on the cutting edge at Outlines gallery."