Parking is scarce along Lawrenceville's main artery, Butler Street, on a Friday night. Bars and restaurants are packed. Come Saturday morning, a line snakes out of a gourmet French bakery. Development in the neighborhood is booming.

"We're the only neighborhood I can think of that has a single-screen movie theater, a bowling alley and a pinball arcade within a block," says Matthew Galluzzo, of the Lawrenceville Corp., a neighborhood development group active since the 1980s.

The 2.5-square mile residential and commercial district boasts old and new, as illustrated in the corporation's logo — a World War I soldier signifies legacy, and a green vine represents growth. "History in the Remaking," reads the tagline below the image.

A look around the neighborhood reveals the new Children's Hospital towering over the historic Allegheny Cemetery and shiny, new condos built just across from riverfront industry. A banner hanging on a chain-link fence advertises "luxury urban living" in planned dwellings with rooftop decks.

It is a neighborhood of contradictions. While most housing stock was built before the 1940s, rents now average $734 a month, according to census data, nearly double what they were 15 years ago. The number of affordable housing units built since 2012 can be counted on two hands. Yet 14 percent of families earn below the poverty line and most kids enrolled in neighborhood schools qualify for free or reduced lunch.

"The neighborhood is still in need," says Galluzzo. "That gets lost in gloss."

Cut through that gloss and head toward the river — down the street from the newly built condos — and you can see a huge remenant of what Lawrenceville once predominantly was: a riverfront industrial neighborhood.

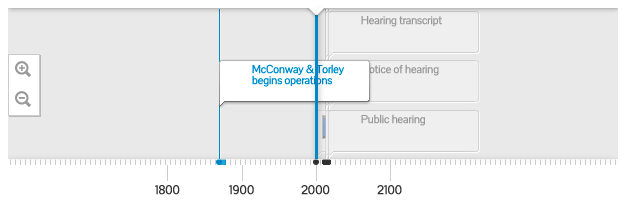

At the end of 48th Street sits McConway & Torley, a 19th-century steel foundry, still operating today with hundreds of workers melting scrap metal and pouring steel castings. The hidden-away foundry supplies much of the U.S. rail industry with important parts that keep railcars safely connected.

But the needs of the neighborhood, residents say, include less noise, less truck traffic and less air pollution, part of which they attribute to the foundry.

"They've been a good neighbor except for smells and air pollution," says Tina Gaser, a resident who bought her home 10 years ago and rents part of her building to a small boutique toy shop.

Taking the company by surprise, the Allegheny County Health Department is just now investigating how much dust and particles from the steelmaker end up in the air and, presumably, in the lungs of Lawrenceville residents. The agency has proposed to drastically cut what the foundry is allowed to produce, which the company says could result in fewer jobs at the plant.

M&T is at the heart of a debate in a changing neighborhood — a complex examination of health and air, abundant and stretched resources, and socioeconomics. And the question that everyone is trying to answer is whether this urban growth and successful industry can co-exist.

"It's our job to make sure there's a community conversation around it," Galluzzo says.