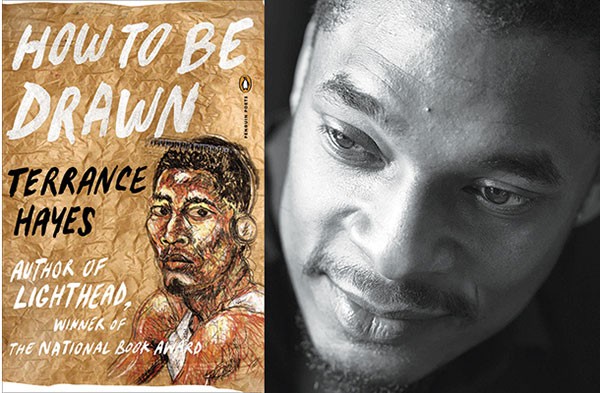

In many ways, Terrance Hayes' new poetry collection, How to Be Drawn, picks up where his previous book, 2010's National Book Award-winning Lighthead, left off. In both, there's the willingness to experiment with form, use of playful language and the confident voice of a writer who found his stride years ago. It's a recipe for success, even as the 95 pages of How to Be Drawn thoughtfully move in new and interesting directions.

It's been a whirlwind of well-deserved achievements for Hayes, now a full professor of writing at the University of Pittsburgh. Since 2010, he's piled up more awards, done national interviews for prominent outlets, had poems published in The New Yorker, received a nod to edit the prestigious anthology Best American Poetry 2014, and won a MacArthur "genius" grant, among other accolades. It's a long way from his early years in South Carolina — where, he claims in an interview, if he hadn't received a hoops scholarship from Coker College, he might have become a prison guard like his mother.

In the new collection, Hayes makes nice use of his mother's profession, ruminating on the complicated nature of passion in "How to Be Drawn to Trouble":

She was a guard at the prison in which James Brown

Was briefly imprisoned. There had been broken man-made laws,

A car chase melee, a roadblock of troopers in sunblock.

I, for one, don't trust the police because they go around looking

To eradicate trouble. T-R-oh-you-better-believe

In trouble. Trouble is how we learn what the soul is.

His lines' musicality keeps readers on their toes, allowing Hayes' speaker to express a tone of acceptance as he explains an incident from his parents' marital difficulties without melodrama: "For many years there was a dancing competition between / My mother and father though rarely did they actually dance. / They did not scuffle like drums or cymbals, but like something / Sluggish and close to earth." The understated language lingers without casting blame.

Reading How to Be Drawn can be educational and, thankfully, the author's website includes links and notes on inspirations ranging from photos and sculpture to obscure books and hip hop. As an undergrad, Hayes studied fine arts, and he possesses a high cultural IQ that seeps into his work through ekphrasis (or literary descriptions of artworks), name-dropping and epigraph. Some of those are more effective poems than others.

"Wigphrastic," written after a collage print by the artist Ellen Gallagher that aims to challenge stereotypes, works for its quirky use of free association that accumulates consonance and alliteration throughout. "The men all paws. Animals. The men all fangles, / the men all wolf-woofs and a little bit lost, lust / lustrous, trustless, restless as the rest of us." It's a delicious cadence that ebbs and flows throughout the poem.

Hayes' considerations of form make him something of an experimentalist. Some of his strongest previous works embraced pecha kucha, a fast-paced Japanese style of business presentation. In How to Be Drawn, he works poems into the form of a séance ("Instructions for a Séance with Vladimirs"), conceptual maps from the Arts & Language movement ("Some Maps To Indicate Pittsburgh") and an Einstein-ian logic puzzle ("Who Are The Tribes"). While it's daring stuff in theory, the writing in these particular poems sometimes feels stifled and academic.

By contrast, a favorite of these experiments is "Portrait of Etheridge Knight in the Style of a Crime Report," in which Hayes filled in a three-part police form to pay homage to the late Black Arts poet by incorporating aspects of Knight's life and his influential poem "The Idea of Ancestry" ("In the cell's darkness, the code of ancestry breaks"). The form Hayes uses here functions as an important reminder about second chances, especially in the face of present-day rates of incarceration among African-American men.

While Pittsburgh doesn't play prominently in How to Be Drawn, the photographs of the Hill District's Charles "Teenie" Harris do. In "Self-Portrait as the Mind of a Camera," based on a retrospective at the Carnegie Museum, Hayes considers the role of the camera as eyewitness to the everyday lives of "people who would be anonymous." In a book full of memorable verse, the ones here might be most sublime. "But I know there are three kinds of looking in every picture: / The way the photographer looks, the way the subject looks, / And, Brothers and Sisters, the way it all looks to you." In an age of "selfies" and Snapchat, it's a thought-provoking reminder about the nature of perspective. And while this poem mostly focuses on visual imagery, as a whole, How to Be Drawn greatly satisfies both ear and mind.