Jim Wrubel, president of the Pittsburgh Triathlon Club, has never swum in the city's rivers — and he doesn't plan to start anytime soon. "I don't want to be in these rivers regardless of fecal coliform count," he says, referring to levels of sewage contamination.

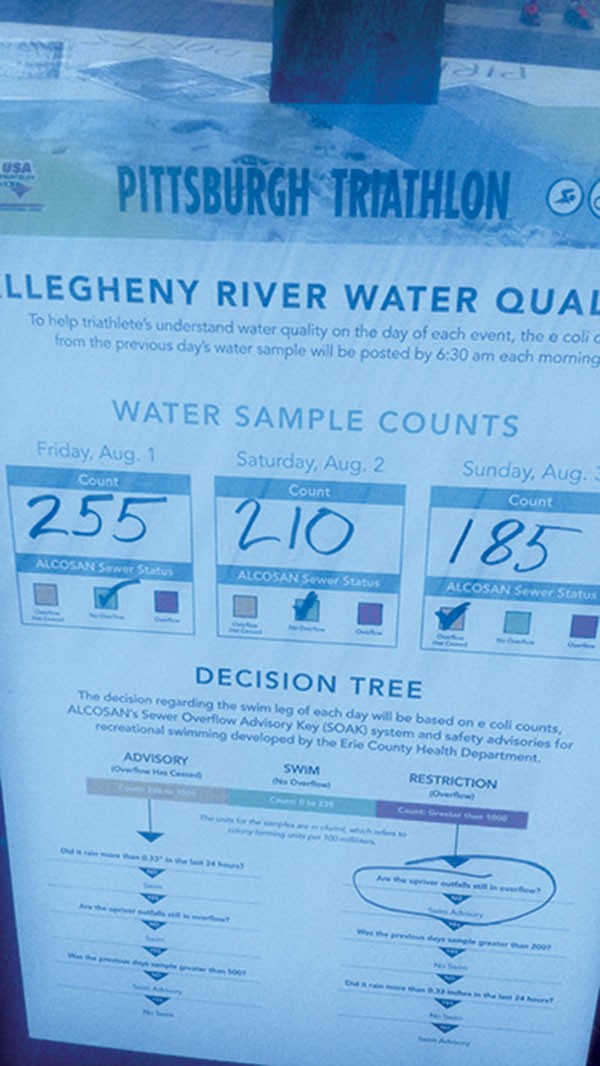

The Aug. 3 Pittsburgh Triathlon offered little incentive for Wrubel to change his mind. As City Paper reported online last week, some triathlon participants were likely exposed to levels of fecal bacteria that qualify as unsafe under state guidelines. Some participants say they felt misled by a chart posted near the starting line, which displayed bacterial counts which they interpreted as showing the Allegheny River's water quality as safe. But those samples were taken before a Saturday-evening storm triggered a sewer overflow warning, likely releasing raw sewage into the river. At least one participant was hospitalized, according to the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.

John Stephen, who created the chart as the founder of Pittsburgh Triathlon host Friends of the Riverfront, expressed regret, saying he was trying to give athletes more information about water safety. "Everyone deserves more and better information about the quality of our river," says Stephen. But on race day, he says, there can be "a large gray area."

It is, in fact, nearly impossible to conduct real-time monitoring of river water quality. Bacterial cultures typically take about 24 hours to grow, and no one is regularly testing the water to ensure it's safe for recreational purposes.

That complicates events like the annual triathlon, where organizers have struggled to make sense of bacterial counts, and to figure out how to inform athletes of the risks of getting into the water. How confident should the public be in the water's safety? And are the rivers consistently clean enough to encourage any large-scale swimming events?

In Pittsburgh, one of the main tools to determine whether the rivers are safe is the Allegheny County Sanitary Authority's sewer-overflow advisory system, which alerts people when there is a chance that sewers are flooded with rainwater to the point that they might be spilling untreated sewage into local waterways. (ALCOSAN says the warnings don't guarantee that sewage is backing up into rivers and streams — just that it could, according to authority spokesperson Jeanne Clark.)

In dry weather, the rivers almost certainly meet state and federal bacteria standards, says John Schombert, executive director of 3 Rivers Wet Weather. But Pittsburgh summers rarely lack for rainy periods. "Historically ... it's about 50 percent of the recreational season that's been affected by overflows," Schombert says.

This past June, ALCOSAN issued sewer-overflow advisories on 11 of the month's 30 days. But ALCOSAN cautions that the river might be "impaired" for up to 48 hours after an overflow, meaning 23 out of 30 days in June included potentially compromised river water. In July, 15 out of 31 days might have included higher-than-normal bacteria counts.

The question, says Schombert, "is how long after these overflows stop does the river water quality return to normal?"

At least one municipality with similar sewer problems has tried to answer that question with smartphone apps and a trove of data.

In response to a consent decree with the federal government, the Metropolitan Sewer District of Greater Cincinnati developed a model to predict water quality based on how previous weather events affected bacterial levels. The agency's website and a "Recr8OhioRiver" app allow users to plug in a type of recreational activity, and predict how risky the activity will be for about two days into the future.

Since "each [overflow] size is different, each rain event is different," it didn't make much sense to just issue 48-hour warnings every time there was a potential overflow, explains project manager Laith Alfaqih. "You want to give better public control over how they recreate."

So far, the predictions appear to be solid: Alfaqih says that when predictions were compared with actual water samples, the model proved about 90 percent accurate.

But while the smartphone app can be effective for casual users, Jonathan Grinder — race director for Cincinnati's annual triathlon — says he's "not going to rely on predictive data" when deciding to call off a race.

That's partly because he gets hard data from the Ohio River Valley Sanitation Commission on the Thursday and Friday before a Sunday race.

Grinder acknowledges that when bacteria levels are borderline, there can be pressure to hold an event as scheduled. A few years ago, he canceled the triathlon because of heavy rain on a Thursday before the race. "People were upset because they wanted to swim and the river looked beautiful," Grinder recalls, "We had to cancel it because it was arguable whether it was safe or not — and if it's arguable, it isn't safe."

Sarah Quesen, the open-water swim leader for the Pittsburgh Triathlon Club, has a different take. She's led open-water swims for the past five years, and never seen an athlete get sick. While she has an admittedly unscientific system for gauging whether the water is unhealthy — "it's basically based on the rainfall" — she thinks that as long as athletes are properly informed of the risks, they should be allowed to swim. Even if bacteria counts are higher than the standards allow.

"I'm worried people will get the idea that swimming in the river is gross," she says. "It's never the same river twice."