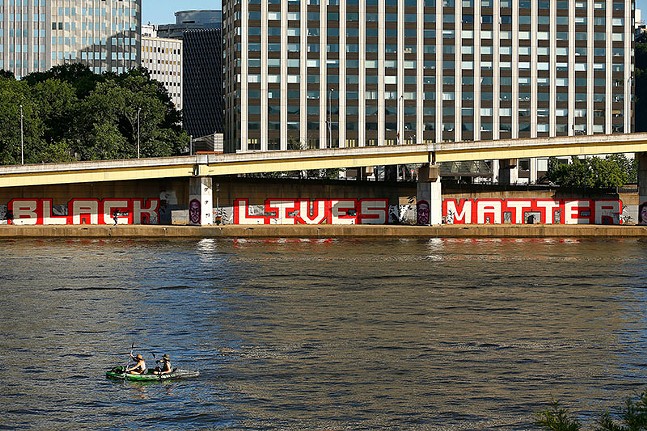

The mural was created on Saturday by a team of yet-unidentified white graffiti artists disguised as a construction crew, who painted over a work by artist Kim Beck commissioned by the environmental nonprofit Riverlife in 2015.

Yesterday my mural got an update! “Black lives matter” is a beautiful declarative poem now writ super large over the...

Posted by Kim Beck on Sunday, June 7, 2020

Since it appeared, users on social media have applauded the piece, with some begging Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto not to take it down, despite it being an unsanctioned work on public property (the site is owned by the City of Pittsburgh and PennDOT). Even Beck gave the work her seal of approval in a Facebook message, calling it a “beautiful declarative poem” and thanking the artists and activists who made it happen.

Sallyann Kluz, director for the Office of Public Art (OPA) of the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council, says she agrees with the message, but disagrees with how it came about, given that it was “designed and implemented by white artists that didn't engage Black activists and artists in the conversation.” Also damaging, she says, is how the work's origins look given the city's history of harshly prosecuting graffiti artists.

“It is incredibly telling that a group of white artists were able to dress as a construction team and do this without getting any attention from police,” says Kluz.

This is echoed by BOOM Concepts co-founder and Black arts activist DS Kinsel, who sees clear bias in how the mural was allowed to be produced without consequence.

“It's confusing that in a city that touts graffiti-busting — and Downtown specifically, where they publish the amount of graffiti they have buffed in their annual report — how white dudes making art alongside a highway underpass dressed in 'construction uniforms' weren't harassed or stopped by the cops,” says Kinsel.

Kinsel points out how some assumed the mural was the work of Camerin “Camo” Nesbit, a Black Pittsburgh-based mural artist who produces work under Camo Customz.

Nesbit is also part of the charitable art collective Wicked Pittsburgh, which includes Max Gonzales, a graffiti street artist once dubbed “Pittsburgh's Most Wanted Artist” by the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police Graffiti Squad. He was arrested in February 2016 and charged with $114,000 worth of property damage.

While local police seem tough on graffiti, Nesbit says “the city basically hates graffiti art, but loves its white sprayers.”

Despite his success, which includes mural projects in Pittsburgh and beyond, Nesbit says it's especially difficult for Black artists to secure coveted public art opportunities in the city, as white artists tend to have more connections and support, giving them an “unfair advantage.”

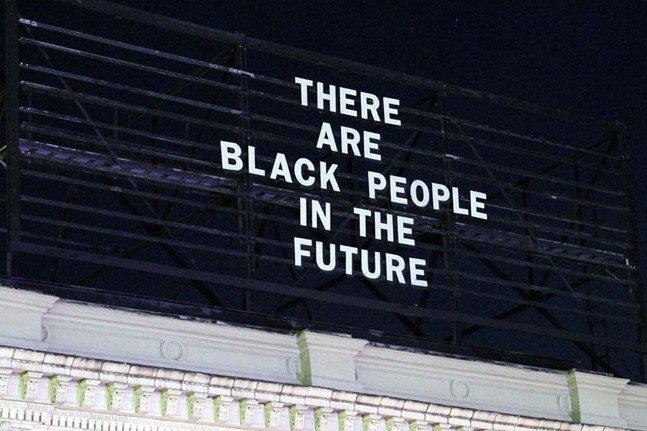

Even when Black artists have been given public art projects, their work has been met with resistance. This was the case in 2018 when prominent local artist Alisha B. Wormsley saw her East Liberty billboard work, There Are Black People In The Future, removed. Presented as part of The Last Billboard project created by Carnegie Mellon professor Jon Rubin in 2013, There Are Black People In The Future was taken down after the company that owns the building over which it was displayed claimed the work violated a lease agreement, and that people found it “offensive and divisive.”

The removal resulted in backlash from community leaders and others who saw it as an attempt to silence Black voices, especially since previous artists in The Last Billboard project had never experienced any problems.

Wormsley says that the ability of the artists to put up the Black Lives Matter mural is a "reflection of white privilege,” where white artists get away with more, and are given more access to space, funding, and other resources.

“I'm sure these projects are done with the intention of supporting the Black community,” says Wormsley. “But it is reflexive of the insidious nature of structural racism. This is what we are trying to address. Black people don't need memorials, they need equity in all aspects of life in this country, including platforms and avenues to present their own vision and liberation.”

Kluz calls the Black Lives Matter mural process “antithetical” to OPA's community engagement practices, which includes connecting local Black artists with commissions and residencies in the public realm. OPA has also facilitated projects with Wormsley related to the There Are Black People In The Future controversy.

Overall, Kluz believes white artists and community members need to step aside and engage with Black artists and activists for leadership on projects that are related to Black Lives Matter, to learn how to follow Black leadership, and to offer up their resources to support that leadership.

“There are opportunities that should be going to Black artists,” says Kluz. “That's really the critical thing to come out of this.”

Kluz confirms that the OPA has been in touch with Nesbit and several other Black artists in Pittsburgh about the mural situation, and is offering support for a public art reform project they are planning, as well as any future efforts.

While still in development, Nesbit says the public art reform project will kick off on Wednesday at the mural site.

“I feel the segregation in Pittsburgh’s art world can be bridged with moments like this,” says Nesbit.

This article has been updated with a clearer description of the mural's location and further clarifications from Sallyann Kluz.