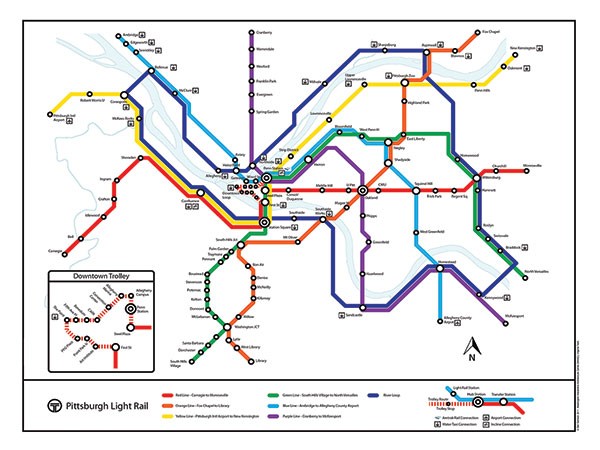

Pitt student Deepshikha Sharma couldn't find a public-transit route for the 18-mile trip from Monroeville to Dormont that would take much less than two hours. So, in what she describes as "a moment of frustration," she Googled "pittsburgh metro map."

And almost as soon as the search results popped up, she was posting a piece of Ben Samson's little-known master's thesis to Tumblr. The paper, which presents a vision for remaking Pittsburgh's transit system, would soon be shared and re-shared — catching the attention of other bloggers who like the idea of a unified Pittsburgh rail system — and soon, it was all over Facebook.

"i need. i want. i must have," wrote "shesonherway" on Tumblr.

In Samson's proposed system, Sharma's original journey would require just one transfer from the red line to the green line. But she could also transfer to any of the five other color-coded lines and get anywhere from as far out as the airports, Carnegie, Fox Chapel or McKeesport and arrive in Lawrenceville, the Strip District or South Side — and almost everywhere in between.

Samson's map also includes a red "spine line," which moves underground from Downtown through Oakland and continues out to Monroeville.

A Squirrel Hill native, Samson created the map while a grad student at Virginia Tech because, he says, "Everybody knows that the biggest problem with Pittsburgh nowadays is its infrastructure and public-transit system. It went viral because it speaks to the core of what the city needs."

The cost? At least $5 billion, Samson estimates, or the equivalent of about 10 North Shore connectors. (That project was so over budget that former Gov. Ed Rendell called it "a tragic mistake.")

To keep costs down, Samson figures up to 80 percent of the system could be created on existing "rights of way"— infrastructure such as busways, HOV lanes, freight lines or remnants of the trolley system. Most of it would be built at street level to avoid digging expensive tunnels.

But is the project feasible in the long run? And even if it is, should Pittsburghers want it?

"The point isn't really, ‘Is this feasible or not?' The point is to start conversations," Samson says, adding that it's only a matter of time "before we have a large-scale transit system."

And even though pretty much everyone agrees the current transit system is flawed, there is hardly consensus on whether a light rail is the way forward.

"I think he presents some really great visualizations of a host of plans that have been out there," says Chris Sandvig, regional policy director for the Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group. "But as a region we need to start the conversation at a different place: What kind of community do we want to live in?"

Sandvig says getting traction on an answer will involve larger debates about regional development. Should the transit system be designed to move people to and from the suburbs? Can it be built to mitigate socioeconomic exclusion "so it's not just some form of welfare"?

Bus rapid transit is the future in Pittsburgh, many argue, because it shares light rail's speed through less frequent station-stops, but can be built at a fraction of the cost. And it has gained some political momentum, with favorable reviews from Pittsburgh City Councilor and Democratic mayoral nominee Bill Peduto and Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald.

For Samson, though, one of the biggest problems with bus rapid transit is its appeal: It just isn't sexy.

"It's really going to be tough to change people's minds to get people to say, ‘I'd love to take the busway.'" That's a problem, he argues, because a key component of transit development is attracting enough "choice riders" — people who have cars, but choose to take public transit.

"Rail has a sense of permanence; everyone is afraid that bus routes will change, or they'll cut routes," Samson says.

Helen Gerhardt, a community organizer for Pittsburghers for Public Transit, agrees that light rail is a noble goal — but it's hard to see past transit-funding crises and the immediate problems they create.

"In a world of scarce resources, that map seems like cake with ... deep frosting," Gerhardt says. "The people I'm working with need protein and vitamin C."