It was surprising, if not unprecedented, when rapper and producer Lord Finesse sued Mac Miller last year over a sample on Miller's 2010 K.I.D.S. mixtape. Conventional wisdom once said that mixtapes were generally safe from copyright suits, as they're distributed for free and don't have the profile of larger releases. But in recent years, more and more artists have been slapped with mixtape-related suits. It raises the question of whether the utility of the mixtape in hip hop is waning ... and whether it's such a bad thing if it is.

The mixtape is a fixture in hip hop: The name stems from "party mix" cassettes made by DJs in the 1980s, but has come to refer most often to unofficial collections of tracks released by MCs. Mixtapes are now generally distributed as free downloads on the Internet, with the biggest hub being DatPiff (www.datpiff.com). Some mixtapes are like demo tapes, especially for up-and-coming artists, but even the best-known rappers release mixtapes in between albums.

"I think mixtapes came about initially because it was a really great way for guys to promote themselves without an album," explains producer E. Dan, owner of ID Labs Studios in Lawrenceville, who has worked with Miller and many other local and national-level hip-hop artists. "It's quicker; it's been a chance for artists to explore."

For years, it seemed mixtapes flew under the radar with regard to copyright suits. While sampling fees were established and grew throughout the 1990s, mixtapes became part of the mechanism hip-hop artists used to release their work without all the paperwork.

"A lot of mixtapes contain unreleased songs," explains Kembrew McLeod, a professor of communication studies at the University of Iowa and producer of the documentary Copyright Criminals. "And one of the reasons songs won't be released is the samples can't be cleared: Permission has been refused, or it's too expensive."

"Generally when you're releasing an album," says E. Dan, "there's a lot of things that have to go on, legally and with red tape, just to put albums together: Clear your songs, get letters, contracts, all that. With a mixtape, it's almost more personal — artists can sort of slap them together however they want to and send them out to the world."

But while mixtapes are often put together with less formality than official releases, they've never really had legal immunity, explains McLeod.

"Mixtapes don't really skirt the law, unless you're talking about the fact that they're [often] under the radar. A common misconception is that just because downloadable mixtapes are available for free, they're somehow avoiding being copyright infringements; that's not the case. There have been a number of high-profile hip-hop artists who have been sued for uncleared samples on their mixtapes."

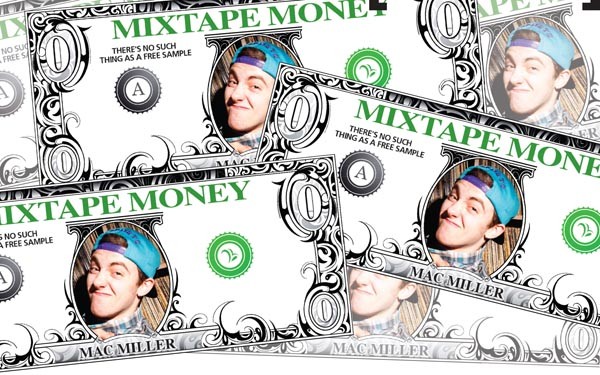

South African singer Karma-Ann Swanapoel sued Lil' Wayne in 2008 for using her voice in a recording on his 2007 mixtape, The Drought Is Over 2. Bobby Poindexter of The Persuaders sued Kanye West for $500,000 last March over a sample on his 2006 mixtape Freshman Adjustment 2. Then last June, Lord Finesse sued Mac Miller and his label, the partly-Pittsburgh-based Rostrum Records, for $10 million over the song "Kool Aid and Frozen Pizza," which heavily samples Finesse's 1995 song "Hip 2 Da Game."

In December, the case settled out of court; neither Lord Finesse nor Rostrum has commented on the terms. The "Kool Aid and Frozen Pizza" video is no longer publicly available via Miller's official YouTube channel, and the track is no longer included on the K.I.D.S. mixtape download on DatPiff.

"So many of these [copyright suits] settle, that there's not a lot of foundations for people to go off of," explains Adam Barnosky, a Boston-based attorney who writes about legal issues for Performer magazine. [The Lord Finesse-Mac Miller case] was an interesting point of law, but it settled, so there was never a decision."

Barnosky explains the basics of copyright simply: "Without authorization, there is really no situation in which you can sample legally, without the worry of a lawsuit." But, he adds, there are some caveats, such as "fair use," which dictates some situations which copyrighted material can be used. Copyrighted work being used for education, work that's transformed by the sampling artists, and samples that are considered de minimus — too small to be significant — are generally protected.

Barnosky and E. Dan are in agreement that mixtape-related suits aren't going away — and E. Dan sees the chilling effect they have already taking hold. "Wiz [Khalifa], right now, has been sitting on a mixtape that's been done since last summer, because of sample clearance issues. He doesn't want to just put it out, after everything that happened with Mac.

"Mixtapes did fly under the radar for a long time, until copyright holders woke up and said ‘They're not selling these things, but they certainly generate money in all sorts of ways.'"

And to some, that might not be an entirely bad thing. E. Dan notes that as a producer, he makes little or nothing to supply beats for a mixtape, as opposed to an album projects. "I'm less and less a fan of mixtapes these days, for a variety of reasons," he says.

Ray Dawn doesn't fear the copyright crackdown much, either. He notes that he and producer Ohini Jonez are currently working on an album with no samples — which is challenging them both to do their best work.

"I wouldn't mind if they started going after people on samples more, because it would actually improve the quality of the work people are putting out."