If local TV was your only news source, you might be under the impression that Downtown Pittsburgh suffered an unprecedented crime wave this summer.

Since mid-July, local television stations KDKA, WPXI, and WTAE produced more than 18 stories combined on criminal activity in Downtown and the ensuing drama that played out between Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto and groups like the Cultural Trust over how to address crime in the Central Business District.

KDKA led the field with more than 10 stories, including multiple implying an alleged rise in crime would threaten future development and scare away Downtown restaurant customers, documenting the horrors of panhandling, and detailing crime statistics.

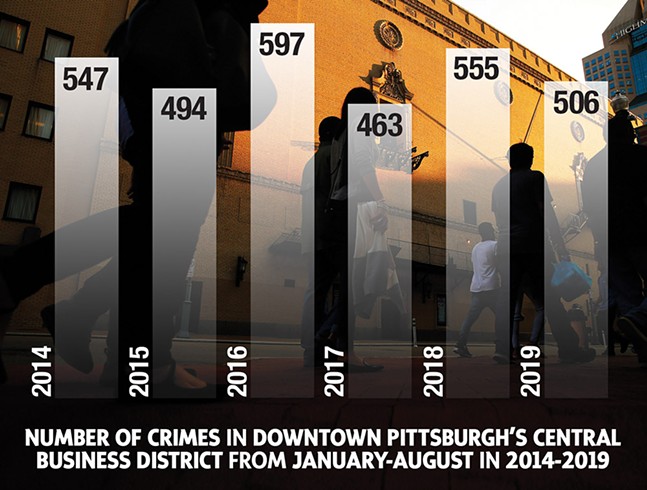

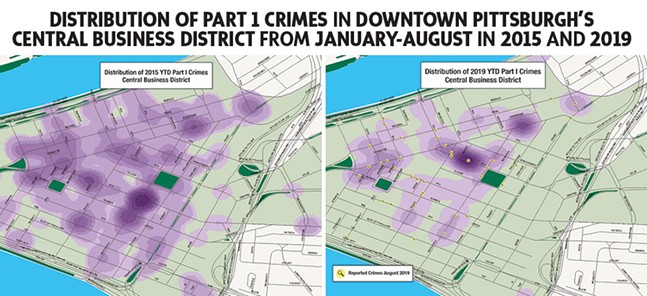

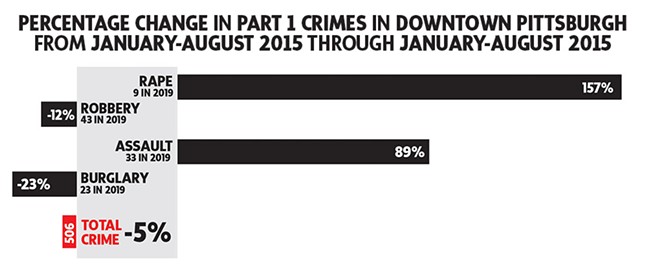

According to the Pittsburgh Department of Public Safety, there were four aggravated assaults Downtown in August 2019, including a fatal stabbing. From January through August, Downtown experienced statistically significant increases in rapes and assaults, with nine rapes and 33 assaults.

This might seem like a cause for alarm, but Part I crimes — murder, rape, robbery, assault, burglary, theft, vehicle theft and arson — were actually lower Downtown than they have been in past years. The four August assaults mark a 7 percent increase compared to the previous five Augusts. The three August robberies marked a 67 percent decrease compared to last five years, and the two burglaries represent a 58 percent decrease. August 2019 thefts are virtually at the same levels as they've ever been.

Statistically speaking, there was no increased crime problem in Downtown Pittsburgh this summer.

But those comprehensive statistics were released on Sept. 12, long after the narrative about a supposed “crime wave” was already established by local media. Dozens of stories about Downtown crime had already been published in July and August, following a letter the Cultural Trust wrote to Peduto requesting a greater police presence Downtown. Kevin McMahon, Cultural Trust CEO, cited a high-profile Fourth of July shooting that occurred Downtown, and issues like panhandling and drug overdoses, as to why he felt the need to request more police.

This letter came weeks before the four stabbings Downtown and each of those assaults garnered high-profile stories, many of which referenced the letter. Initially, Peduto was critical of such calls to add police, telling the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette he wasn’t interested in using Pittsburgh police to round up the homeless, people with substance abuse disorder, and those with mental health issues.

But with each assault came more coverage asking what Peduto should do about crime. By the end of August, the mayor announced he would add patrol officers Downtown. Peduto previously said in July that Pittsburgh employs the most police officers it has in 15 years.

This narrative points to several problems in crime reporting that lead to perceptions outweighing facts.

David Harris is a professor at the University of Pittsburgh and a nationally renowned expert on policing. He followed the crime reporting closely over the last couple months and wishes more context about Pittsburgh’s crime would have been provided.

According to the FBI statistics from 2017, Pittsburgh –then the 65th largest city in the U.S. — had the 47th highest violent crime rate and the 62nd highest property crime rate of the nation’s 100 biggest cities. Pittsburgh had about 656 violent crimes and 3,114 property crimes per 100,000 people.

For context, Buffalo had significantly higher violent and property crime rates than Pittsburgh. Even Fremont, Calif., a large, but sleepy suburb which was once ranked as one of the safest U.S. cities, had 182 violent crimes per 100,000 people. Des Moines, Iowa had a slightly higher violent crime rate than Pittsburgh.

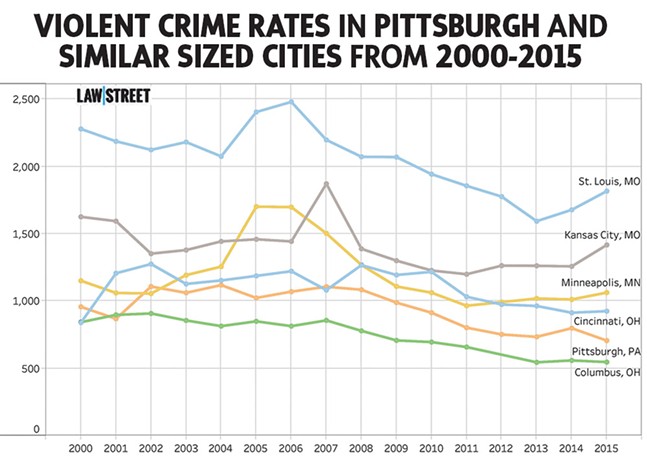

St. Louis had more than triple Pittsburgh’s violent crime rate, and Albuquerque, the city with the highest rate of property crimes, had more than double the property crime rate of Pittsburgh.

“We may be a little over the average for a city our size, but you have to put it into context. We are at especially low rates of crime, especially violent crimes,” says Harris. “You look at the ‘90s and late ‘80s, it was a different world — there wouldn’t be anybody moving around in Downtown back then.”

Pittsburgh, like most big American cities, saw its biggest violent crime rates in the early 1990s. In 1990, Pittsburgh experienced 1,356 violent crimes per 100,000 residents. Violent crime rates fell from there before rising again in the early 2000s and reaching another peak in 2004 with 1,119 violent crimes per 100,000 residents. Since then, violent crime rates in Pittsburgh have dropped significantly to half of their peak in 1990.

Harris says this drop in crime likely opened up many opportunities to revitalize Downtown into the neighborhood it is today. According to the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership (PDP), 2018 attendance at Greater Downtown concerts, art galleries, sporting events, shows, and museums totaled more than 8.8 million people. This was a 2.5 percent increase compared to 2016, not to mention the 720,000 people that attended Downtown festivals in 2018.

PDP has also documented 118 new businesses that have opened Downtown since 2016.

“Because crime is at such historically low levels, you can do different things in Downtown,” says Harris. “You can walk over to the Benedum after eating at a restaurant — those things aren’t possible in a crime wave. The very existence of this situation Downtown shows that things have changed a lot.”

Harris says this doesn’t mean that Downtown Pittsburgh isn’t without problems, noting increases in homelessness or people with substance use disorder, but says this is not unique to Pittsburgh.To address these issues, Harris thinks the answer can't simply be increasing police presence. He says we need a nuanced approach to help those living with mental health issues, addiction, and homelessness, like providing more services or a campaign to connect people to services that already exist.

“In general we ask our police to do too much,” says Harris. “Police are asked to respond to mental health issues and to panhandling. Those are not the issues they are trained to be focused on.”

Harris also questions the strategy of adding police officers to lower violent crimes. Peduto has defended how many police officers were Downtown before he added more, saying that officers were in close proximity and sometimes directly on the scene when assaults occurred.

“One of the stabbings occurred when a police officer was standing right there,” says Harris in reference to the fatal stabbing that occurred on Sixth Street. “This is the best example that this is not chiefly a policing issue.”

Harris says there should have been more thorough reporting on Pittsburgh crime from local media outlets. Instead, he says the narrative that emerged was simple: more crime necessitates more police.

“The media in general gravitates towards simple and easy to understand opposites,” says Harris.

Duke University professor Sara Sun Beale wrote a paper in 2006 called “The News Media's Influence on Criminal Justice Policy: How Market-Driven News Promotes Punitiveness.” In it, she wrote that local TV stations manipulate crime and violence coverage as a marketing strategy and cites a study of more than 16,000 local news stories from 57 local stations showing that crime reporting wasn’t driven by actual crime rates in the area, but more by establishing a brand identity to local advertisers.

Beale concluded in her paper that high-crime coverage on local TV didn’t actually reflect high crime rates in a given area.

“For that reason, the incidence of crime stories in the local news bears no relation to crime in that area,” Beale wrote. “Given its feature focus, high-crime stations not surprisingly trained their stories more on the crime commission and the alleged perpetrator than the workings of the criminal justice system.”

In fact, in August 2016, there were eight assaults and 20 robberies Downtown, twice as many assaults and about seven times as many robberies compared to August of this year. But the media coverage didn't react then as it did this summer.

A Google News search of “Pittsburgh Downtown crime,” looking at articles from July 17 (the day the Cultural Trust letter was published in the P-G) to September 7, shows dozens of reported stories, letters to the editor, and editorials about crime in Downtown.

The same Google News search for the same time period in 2016 resulted in no crime-related stories. Even when conducting searches for “Pittsburgh Downtown assault” and “Pittsburgh Downtown robbery” for the same time period in 2016, just two crime-related stories emerged: an alleged assault near the David L. Lawrence Convention Center and a robbery at a bank on Smithfield Street, both in August 2016.

When Pittsburgh Police released its summer crime stats this month, TV news and local publications wrote stories about the statistical decrease. But the damage was already done. Peduto added extra police Downtown in late August. Police horses have been increasingly utilized Downtown in the time since.

It’s not uncommon for local TV news and newspapers to spend time and effort covering crime stories. Beale noted this in her 2006 paper, writing that the “emphasis on crime in the local news depends not on actual crime in the area, but on viewer interest in violent programming.”

However, Pittsburgh media consumers don't particularly believe crime coverage is of the utmost importance. According to a Pew Research report published in March, 36 percent of adult media consumers in the Pittsburgh region think crime coverage is very important. This is close to average compared to other large U.S. metro areas, with 51 percent of Memphis-area residents thinking crime coverage is important on one end and with 26 percent of Los Angeles residents on the other end.

Regardless, those coverage preferences might not be having much effect on how local media covers crime. Beale says up-to-date data used in her 2006 study isn’t available, but notes that media dynamics haven’t changed much since 2006, including financial pressures and what producers think the public wants. It could actually get worse.

“If anything, the pressure on local news outlets has increased very significantly, as they face competition from online sources as well as the tremendous number of channels to which most TV viewers have access,” says Beale.