Damon Young is aware that the state of Black Pittsburgh is not good. Maybe too aware.

He is aware that economic opportunity for Black Pittsburghers’ is among the worst in the nation, even as white Pittsburghers' fortunes are rising. He is aware that hundreds of Black people are being pushed out of their neighborhoods each year, and hundreds more are leaving the Pittsburgh region altogether, usually flocking to cities like Atlanta, Charlotte, or Washington, D.C.

“Whatever the national average is, the disparity is greater in Pittsburgh,” says Young of statistics relating to the economy, health, and other issues. “We are a city that has always treated Black people like they should just be swept aside.”

But here he is. Sitting in Arnold’s Tea in the North Side, just a few minutes away from a house he recently purchased in the neighborhood. He and his wife just had their second child.

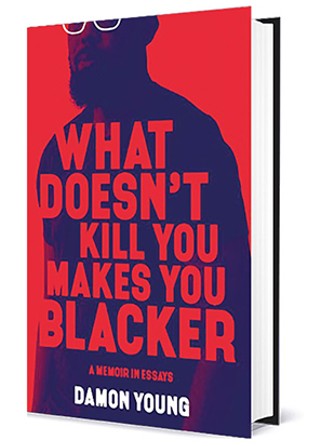

Young’s star has risen quickly over the last few years. The blog he co-founded with Panama Jackson, Very Smart Brothas (VSB), was purchased by Gizmodo Media Group and is now hosted on The Root, one of the nation’s largest Black media sites. Young’s first book, What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker, is coming out at the end of March. It’s the first of a two-book deal with Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins. In his new book, Young explores topics he hasn’t touched on as much in his previous writings, like confronting the roles that homophobia and masculinity played in his adolescence as a star athlete.

Young, now in his 40s, could have picked anywhere in America to live, to write, to raise his young family. But he has no intentions of leaving Pittsburgh, even if he recognizes this decision has shortfalls. He says being Black in Pittsburgh can be traumatic and that finding comfort is no easy task.

In a recent blog on VSB, he elaborates:

“We don’t have the luxury of easing into blackness; of finding quick comfort; of lazing into immediately friendly spaces. If you want to be black in Pittsburgh, you need to be motherfucking intentional about it. You need to research. You need to procure. You need to excavate. You need to google.”

But he sees hope in Pittsburgh too. He thinks the Black arts-and-writers scene is really starting to thrive and will continue to grow. He doesn’t fool himself into thinking this can create the kind of broad-based prosperity that will lift all of Black Pittsburgh. But it’s the path that is emerging for some Black Pittsburghers like Young, and maybe something that can help the community cope with living in a city where they often feel like an afterthought.

“If I had to rely on Pittsburgh, I would have left Pittsburgh,” says Young of his national writing success. “Since I don't have to rely on Pittsburgh, I get to stay in Pittsburgh.”

Young was born and raised in Pittsburgh and spent his formative years in East Liberty. His last few teenage years were spent in Penn Hills, where he became a star basketball player for Penn Hills High School. Almost his entire life has been spent in and around Pittsburgh, except for his time at Canisius College in Buffalo, NY, which he attended on a basketball scholarship.

His book is a memoir of his life experience in Pittsburgh, never ignoring what it’s like being Black in the Steel City. Young’s writing has an easy wit about it, but he says there was a concerted effort to document the stress, oddities, and trauma that came with growing up Black.

“So much of the conversations in the book are about race and about trauma,” says Young. “The neurosis that is bore out that. Each chapter dives into a different idea.”

A Brookings Institute study showed that from 2010-2015, the median wage increased 8.1 percent for whites in the Pittsburgh region, but decreased 19.6 percent for Black Pittsburghers. The white wage growth was well above the U.S. average over that time span and the Black wage drop was well below U.S. average.

“I feel like we have this cognitive dissonance,” says Young. “The city wants to believe it is the bastion of progress, but that progress doesn’t extend to Black people.”

Young explains in his book how this inequality has led him to experience the “hyper-cognizance” of his Blackness. He writes in his prelude that he is constantly asking himself questions like “Did that happen because I’m black?” and “If this is happening because I’m black, how am I supposed to react as a Professional Black Person?”

Eventually, Young says, constantly worrying about one’s place in society causes so much stress it can affect an entire community’s outlook on a region. Young understands the nihilism attached to being Black in Pittsburgh. He feels fortunate that he has a strong network of family and friends here, and his career success as reduced that burden too. But he realizes many Black Pittsburghers aren’t as fortunate.

“It weighs on you,” says Young. “There are points that you wish that you didn't have to be as cognizant, when you don't have to be as aware.”

Young says these stressors are only exacerbated by Pittsburgh’s derelict state of comfortable Black spaces. He notes how Pittsburgh lacks a middle-class Black neighborhood or a business district were Black people congregate like U Street once was in Washington D.C. He says there are restaurants, churches, and clubs patronized by Black Pittsburghers, but there is intentionality about inhabiting those spaces.

“You don’t have any spaces in your life where it is just chill spaces,” says Young. “You are living in every moment. If you can’t find those things here in Pittsburgh, you are going to go to a place where those things aren’t as hard to find.”

However, Young says talented Black writers and artists are starting to congregate in Pittsburgh as an intentional choice to practice their craft. He says the region’s comparably affordable living costs have fostered a community where Black writers and artists are thriving. Writers like Pittsburgh City Paper columnist Tereneh Idia, CityLab staff writer Brentin Mock, and The Undefeated senior writer Jesse Washington; artists like Vanessa German and Alisha B. Wormsley, fashion designers like Tara Coleman, and multimedia artists like Young’s cousin sarah huny young.

“The artists that are here, the ones that are very intentional about their work, this is a city where this is happening,” says Young.

Young’s book isn’t just about stress of being Black in a region that is overwhelmingly white. Young also writes critically of masculinity in Black Pittsburgh.

The chapter “No Homo” is an honest critique of the homophobia that persists in some African-American communities, and the connection it has to patriarchal norms. Young shares anecdotes of how people would accuse him of being gay because he didn’t have a girlfriend.

“But if there was nothing wrong with being gay, why was there something wrong with being ‘soft’? And how are these two things connected? … It was used to describe the boys who seemed to be more interested in the things girls were supposed to be interested in than the things boys were supposed to be into.”

Young hopes his stories reach other young Black men who reject homophobia, the ones who question what their role should be in an evolving society.

“I hope this is a book that helps people reduce harm. And helps people widen their spectrum,” says Young.

And this is really what Young’s book is about: describing memories of stresses about race, gender, family and economics. He says writing the book was a catharsis: a way to understand and comprehend, as his prologue notes, that “living while black is an extreme sport.”

The book and Young’s writing in general are extremely personal, but they appear to be therapeutic, a way to live through the stresses Young documents about being Black in Pittsburgh.

“The book was for me,” says Young. “It was a book I needed to write.”