Some would call it a tough crowd. On an April afternoon, Vanessa German stands before 50 kids dressed in the dark-blue scrubs of Allegheny County's Shuman Juvenile Detention Center. The teen-age residents face charges for things like robbery, guns and drugs. Most have been sent here before; many will be back.

But now it's Jazz and Poetry Month, and the residents, mostly boys, sit at cafeteria tables in a semi-circle in the assembly room, with about 30 Shuman staffers seated in back.

German, 34, wears one of her homemade, ankle-length dresses, handpainted with expressionistic streaks and the head and shoulders of a black woman. She stands with a microphone before plate-glass windows decorated with poems by residents. One reads, "Anger is black. ... Anger makes me feel like I'm crazy." Another goes: "When I feel misunderstood I am like ... a caged animal."

German begins by telling how she became an artist and performance poet who's stood on stages around the country and overseas. "I have always been the type of person who loves stories," says German. "How many of you feel you have a lot of stories to tell? Anybody?"

She pauses, and continues. "Besides the three people who are raising their hand, I bet all of you have stories to tell."

German tells one of her own. It's about her suicide attempt, some 15 years ago, and what happened next:

I remember waking up after I had tried to kill myself. And one, being humiliated that I was still alive. [...] People would just look at me and think that I was worthless, that I was just this stupid girl who did this thing. When I finally kind of came out of being seriously ill, I remember, something finally switched in my mind where I didn't feel like I didn't want to be alive anymore. I remember looking around and seeing that all the colors around me seemed brighter. And people's faces seemed more animated and more alive. [...] [T]hat was when I first decided that I really wanted to stand up and tell my own stories ...

Replacing self-loathing with self-expression is a big theme in German's work. She abandons the mic to recite a sermon by Martin Luther King Jr., and one of her own love poems. Her big voice fills the room. Deep in performance, she'll throw her head back to sing a few words; one arm might undulate, like a belly-dancer's, or her hands slip into sign language. She also reads aloud from the residents' writings taped to the windows.

Then one resident, a girl, rises to read her own poems. She stands beside German and reads in a halting but clear monotone: "Every time I turn around I'm in a situation. / I get in trouble by the law and have to pay citations. / Business involving drugs, gangs and killing so young / I'll write down every word that comes to my tongue."

The residents applaud. German praises the girl. "You decide what your life means and what your situation, those experiences mean, and you decide what you're gonna do with them every day."

German winds down with one of her signature pieces, "If My Hands Were Anything But Hands," which she's performed in venues as different from Shuman as 2007's PopTech festival, a prestigious national gathering of thinkers and artists in Maine.

Part of it goes: "If my hands were anything other than hands, they would be mirrors. I would hold them up to your face, and you would be able to see yourself as immutably remarkable and beautiful as God made you, and you would never, ever try to hate yourself to death again."

German concludes her hour-long talk by walking to one table and slapping palms with the girls seated there. Coming to the girl who read aloud, she leans in to whisper something. The girl smiles and says, "Thank you."

"Who Would Come for Me?"

Walking Downtown with German can be an exercise in roving validation. Leaving April's Equal Pay rally in Mellon Square -- where she exhorted veteran activists and high school girls alike to fight for equitable wages for women -- German doles out compliments to strangers. "I like your shoes," she remarks to one woman. "That's such a pretty cake," she tells a culinary student carrying a plastic cake container.

But German can rip, too. In 2004, for instance, she won a national competition called SlamBush. At the finals in Miami, co-hosted by Chuck D of Public Enemy, German performed "Thank You George Muthafuckin' Bush," blasting the 43rd president on Iraq, gay marriage and more.

"Thank you," the poem began, "for makin' it easier for me / to get a TEC-9 or AR-15 than a Pap smear and a good education."

Her range is one reason German, who lives in Homewood, is among Pittsburgh's most powerful live performers. She's also a sculptor whose distinctive, richly detailed works -- inspired by both Central African "power figures" and iconic American "tar baby" imagery -- are increasingly acclaimed.

Though she's acted for local theater troupes, she's best known for solo works like 2008's Testify, which used storytelling, poetry, song and video to contrast Pittsburgh's "most livable city" accolades with the struggles of black residents. Upcoming is Root, her "spoken-word opera," which, on May 20, kicks off First Voice: A Pittsburgh International Black Arts Festival, at the August Wilson Center.

"Vanessa is absolutely the Anna Deavere Smith of our generation," says Root director Heather Arnet, referring to the playwright and actor best known for Twilight, her multi-character evocation of the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

In the mid-2000s, German was part of Pittsburgh's nationally competing poetry-slam team. At local venues like the Shadow Lounge, "Usually, she tore the house down," says Shadow owner Justin Strong.

As effusive as she is onstage, in social situations German sometimes seems shy. "Vanessa is an enigma for a lot of people. You see her and she's gone," says Kim Ellis, a fellow spoken-word artist and activist who performs as Dr. Goddess. "I think that she lives in multiple worlds" -- artist, activist, black woman, out lesbian.

German chuckles at the suggestion that she stands in different worlds: "I feel like, I am what I am."

Last fall, she was among the performers Texas Southern University invited to honor gospel star Yolanda Adams. On May 16, German was among the speakers at a trendy TEDx gathering of artists, thinkers and entrepreneurs, at MIT.

German's work often revisits, and re-imagines, history. In February, she premiered "Let Her Be a Sweet Thing," a suite of five poems written to complement an exhibit at Pittsburgh's Toonseum art gallery, about a little-known 1950s comic book promoting the civil-rights movement.

German focused on Claudette Colvin, a Birmingham teen-ager arrested for refusing to yield her bus seat to a white woman before Rosa Parks. Colvin is half-lost to history: Civil-rights groups declined to back her, as they'd back the older, more stoical Parks just months later. But in "Sweet Thing," German imagines Colvin's fears, from violence by whites to recriminations from black church ladies saying she shouldn't cause trouble: Colvin, German recited, "could tell us what it is like to be nothing."

German wrote "Sweet Thing" at the invitation of Carlow University assistant professor Sylvia Rhor, who curated the show. Rhor took her students to German's performance. "[They] left here more inspired than I ever saw them in the classroom," she says.

German says her own inspiration came largely from her identification with Colvin, especially the girl's time in jail. "Who would come for me," she wonders, "if I was the first one who scared people?"

"Called to Do Something"

German is a champion convocationalist -- a social-justice advocate regularly invited to commence rallies and meetings, and who performs annually at Pittsburgh Pride, Downtown's LGBT street festival.

But German's exhortations to strength come from a deep understanding of insecurity, the kind she imagines Claudette Colvin felt.

Her performances are seldom as explicitly autobiographical as her Shuman Center talk. Discussing her suicide attempt seemed appropriate there, German says, but she rarely does so anymore: The story now feels "flat." Yet German still battles self-doubt and depression.

"She uses her work to work though a lot of her own emotions and fears and concerns," says Janera Solomon, a friend and sometime collaborator. "When she's rallying the audience ... that's also a cry to herself. I think that's one of the reasons her work resonates with people."

Solomon, who heads the Kelly-Strayhorn Theater, says that unlike many performers, German is unafraid of audiences. If anything, some audiences fear her. While some viewers "feel as though they're being called to do something," Solomon says, "other audience members shrink back."

"I don't think people realize how amazing their lives are," says German. "Anything that I talk about, it always comes back to a place of saying, 'But you are valuable all by yourself'" -- even though German herself often struggles to remember that.

She calls her boldness in performance "a fearlessness born out of fear."

"I grew up as a fat, nappy-headed black girl," she says. "Everything around me was telling me that I was ugly."

German was the middle kid of five growing up in Central Los Angeles, a vibrant if volatile mix of blacks, Latinos and Asians. Her father, James, was an information-technology specialist for Toyota, and German says the kids felt "really fortunate" to attend the Los Angeles Center for Enriched Studies, a prestigious public magnet school. Their mother Sandra, herself a classically trained pianist and fiber artist, also tutored the children aggressively at home. Later, she made them memorize poems and perform them aloud.

But German also recalls growing up in clothes bought from flea markets, or made by her mother; stretching dollars at the grocery; and fearing the drive-by shootings outside their door.

"Vanessa was always special," says her mother, Sandra. "She always had an insatiable hunger to ... go beyond what was right in front of her." Sandra recalls discovering the intricate carvings her teen-age daughter had made in her bed's wooden head- and footboards: "It was like cuneiform. It was stunning."

When German was 14, the ground shifted. Her father was transferred to small-town Loveland, Ohio, northeast of Cincinnati and worlds away from L.A.

"It was a desert," says Sandra German, and her children were "devastated" by the change. Having more than doubled Loveland's black population, the German family saw "KKK" spray-painted on their mailbox, and were questioned by police over whether they really owned their home.

German says white students called her "nigger," and she remembers wondering, "How do you not become these mean kids who are trying to feel better about themselves by being mean to you?"

Her answer: Do it all -- studies, sports, art. Partly, German says, she simply retained "that sense of mortality" from Los Angeles, where kids got shot: "I would invest fully in the life that I had, while I had it." Much of the rest was defiance: "I'm a nigger? Well, watch this."

"A Shape That I Want"

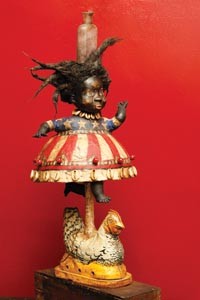

"The Tioga Street Soul Queen, or Everything Old Is Made New Again and Again and Again" is a 4-foot-tall black female figure wearing a necklace of tarnished teaspoons, spark plugs, cowrie shells and two big rusting bolts. Its pedestal includes an old wooden Squirt soda-pop crate and the wooden base of a porch column. The figure's legs are rolled with fat, with daintily chubby feet and articulated hands.

In its belly, small double doors guard a tiny cabinet containing a gilt-framed mirror, a plastic alarm clock and a little plastic boy. Above that, an antique metal spigot juts from between her naked breasts, and a golden bird bursts from her dark red lips. Mounted on her back is another mirror. On her head, like a translucent totem, are stacked a clear-glass wine jug and a glass lamp body.

German created the sculpture for Responding, a group show at Downtown's Future Tenant gallery. Works were to be made in reaction to a particular place; German chose a vacant lot near her house, on a corner known for prostitution and drug sales.

German calls "Soul Queen" a "spiritually utilitarian object" -- art meant to be used, even added to, like a shrine. "If this sculpture is on this corner, the women who work on the corner can look into it, and they can see themselves," she says. "And because it's public art, they [can also] see it being taken care of, then they know that there's something special about that."

German, who is often the only black person at the arts conferences she attends, is acutely aware of the role race plays in her work: "I'm completely obsessed with African-American life and stories." Yet in its focus on self-worth, German's work builds bridges to people who might not otherwise have much in common with her.

"Soul Queen" was commissioned by Future Tenant curator Anna E. Mikolay, who says of German: "I think her work has a voice for a part of society that doesn't say what it has to say, or doesn't even know it has to say something."

More people are listening: Last year, for instance, German won two awards for a sculpture she entered in the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh Annual, at the Carnegie Museum of Art.

German moved to Pittsburgh in 2000. After a couple of years at the University of Cincinnati, she was living in Los Angeles, but helped her parents relocate here (when her father was transferred again). She stayed in Pittsburgh after deciding that "geographic location doesn't make you successful." She lived with her parents in Monroeville until three years ago, when she rented the Homewood rowhouse she now shares with her partner.

The unfinished basement contains her studio. Its shelves hold plastic bins full of stuff she's found, much of it in lots and streets near her home: chunks of wood, rusty bolts, empty plastic bottles. There are also doll parts: legs, arms, heads.

Many people assume German's sculptures are simple assemblages -- found dolls dressed with found objects. In fact, she makes them almost from scratch.

"I sometimes will start with a doll," she says. "Most of the time they're not the proportions I like, so I'll cut them apart ... and build out a shape that I want."

German forms the shapes with strips of rag sopped in a mixture of plaster and wood glue, plus materials like scrap foamboard. The black hue is a mix of paint and roofing tar.

Then there's "all that stuff I do to make it look like it's this ancient piece that is revered" -- things like scarring the figure with a blade, or adding streaks of white paint.

Each sculpture's adornments, meanwhile, are symbolic. She gestures to an in-progress work, a female figure still all plaster-white, a small cabinet set into its torso. "This piece is building itself like an apothecary kit," she says. She holds up an opaque white jar the size of a matchbox. "This would be like, 'This is a courage tincture.'"

"Spoons are always giving and receiving love," says German; shells are "like bones. It's like adding ancestors."

German's dolls represent an alternate history, playing ironically with the "tar babies" of early 20th-century advertising iconography.

"I like to imagine that the things I make have been around for a long time," she says. "What kind of world is it that they existed in? And how are people different, because you got to play with this black baby -- who's really black. She's not brown, she's not dark brown. ... What kind of people are we, if these things are precious to us?"

"Write Myself a Doorway"

German calls her new show, Root, a "spoken-word opera." It's an hour of her on stage with a desk, a couple of chairs and a couch, plus some video and a musician. While Root covers everything from gun violence and Hurricane Katrina to the audacity of Ella Fitzgerald, its title refers mostly to German's love of poetry.

She opens by recalling her childhood. "I fell in love -- with the way a sharpened pencil felt in the palm of my hand," she recites. "All I got to do is write myself a doorway and then walk myself right on through it." Sitting at the desk, she says, "This is how I stay alive."

Root grew from German's early love of language -- and her belief that a person is born with everything she needs to survive.

"So all the things that you want to change, and all the things that you look in the mirror and you hate -- what if you embrace those things?" she says. "What if all the energy isn't going to despising yourself?"

She cites her own attempts at weight loss. "What if I just relaxed about it? What if I focused on doing what I love? What if I write?"

And when she wrote, she found, "I wouldn't be all obsessed with eating. ... And so that was just something that I would give myself. And I thought, 'I could give that to other people.'"

Last year was a wild ride for German. A high point was being selected as one of six recipients of an August Wilson Center fellowship. The award let German hire a director for Root: Heather Arnet, a past collaborator who's also head of the Pittsburgh-based Women & Girls Foundation.

But though she recently acquired health insurance (thanks to her partner's domestic-partner benefits), the year ended with a diagnosis of a long-running stomach problem: German has a large fibroid tumor on her uterus. It's likely benign, but surgery is scheduled just days after she premieres Root.

She says the doctor told her, "Dude, you're gonna be OK. You just have to deal with this." But after telling German the name of the tumor, the doctor added, "Do not Google this ... You could get scared for no reason."

German is following that advice: "I just can't afford to be shut down by fear."