How unloved is the Stephen Foster statue sitting on Forbes Avenue in Oakland, by the Carnegie Library? Even the guy who wrote a new play celebrating Foster's music hates it.

"Why that statue's still there, I don't know," says Martin Giles, whose Beautiful Dreamers opens April 15, right across the street, in a building named for Foster.

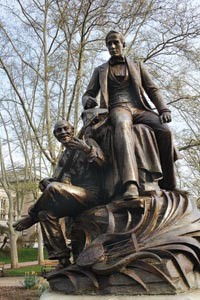

Mark Brentley Sr. hates it even more. The bronze statue depicts an elderly black man, raggedly clothed and barefoot, sitting at Foster's feet and contentedly playing banjo.

"It's just offensive on every level imaginable," says Brentley, an African American and a Pittsburgh Public Schools board member. "I just wish I had a pickup truck strong enough because I would pull [the statue] off with a chain. ... It is a mirror of this city's policy [toward] and treatment of people of color."

The statue dates to 1900. Using money from a public fundraising drive, the Pittsburgh Press commissioned sculptor Giuseppe Moretti to memorialize the famed Pittsburgh-born composer. According to the book Discovering Pittsburgh's Sculpture, the design was suggested by Press editor T.J. Keenan, who imagined Foster "catching the inspiration for his melodies from the fingers of an old darkey reclining at his feet strumming negro airs upon an old banjo."

Some 50,000 people lined the route along which the statue was trucked to its original site, in Highland Park. (It was moved to Oakland in 1944.) At the dedication, 3,000 area children sang Foster tunes, led by Pittsburgh Symphony director Victor Herbert.

The late African-American activist Florence Bridges fought for years to have the statue moved indoors. Brentley says community groups listed the statue among the reasons the NAACP should not hold its 1997 convention here. Brentley also recalls fruitless appeals to Mayor Tom Murphy.

Ironically, the musician in the statue is meant to represent the subject of Foster's song "Uncle Ned" -- which, although written for minstrel shows, was then groundbreaking for its sympathetic depiction of a black man.

A plaque explaining that historical context would help, say observers including Deane Root, the Foster expert who heads Pitt's Center for American Music. Root says that prior to the statue's refurbishment, in 2001, he even submitted text for such a plaque. But he never heard back from the city.

"A plaque would be my first stab at taking care of anything like that," agrees

Morton Brown, the city's current public-art manager. But Brown disputes that statues like the Foster memorial promote racism: "I think people understand them as being products of their time."